Aim: To assess histopathological patterns in the endometrial biopsy of patients presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding.

Methodology: One hundred eight females with the complaint of abnormal uterine bleeding were enrolled. A gynecological examination was done. Dilatation and curettage were carried out. Specimens thus obtained were stored in 10\% formalin. The slides were examined under a microscope, and the various histopathological patterns were assessed.

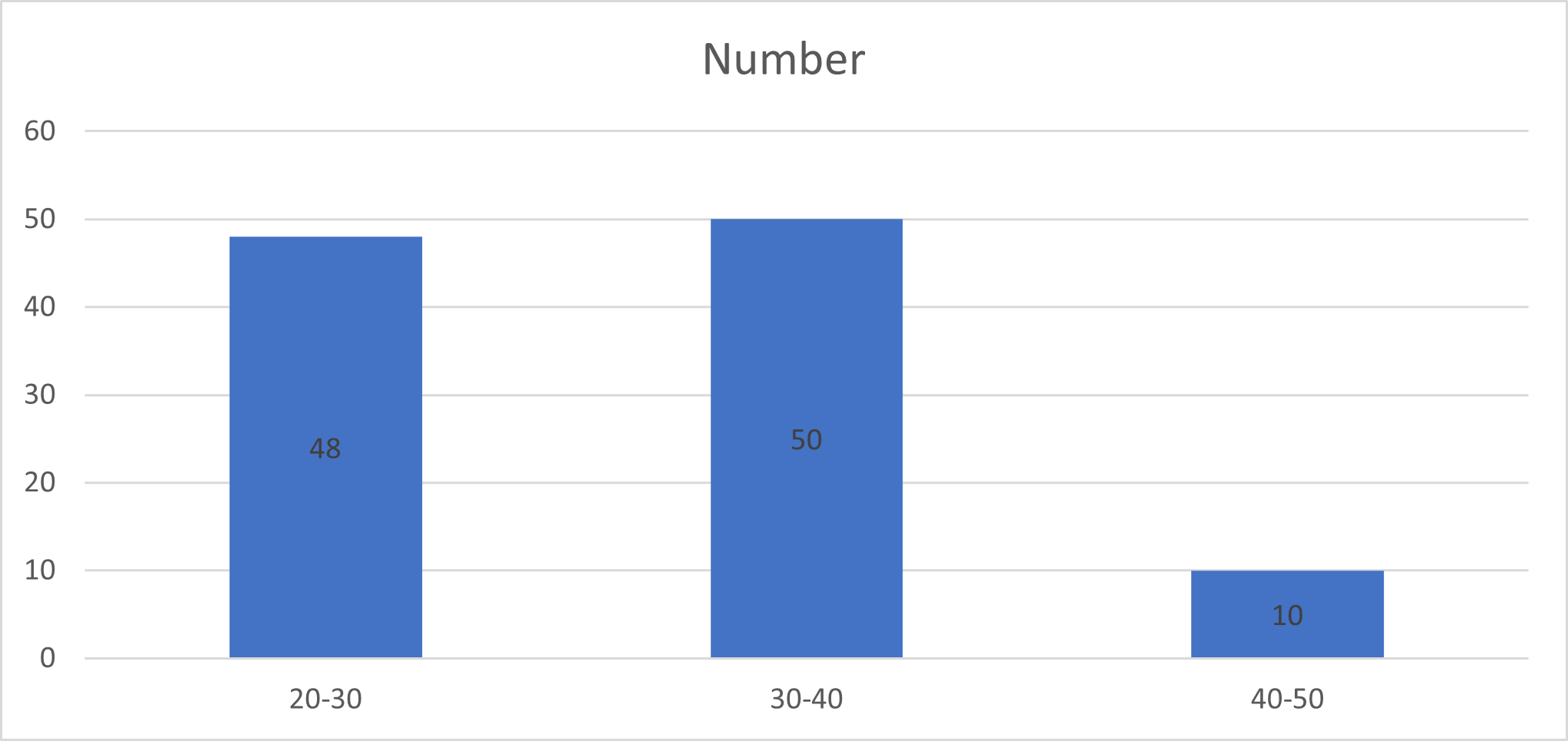

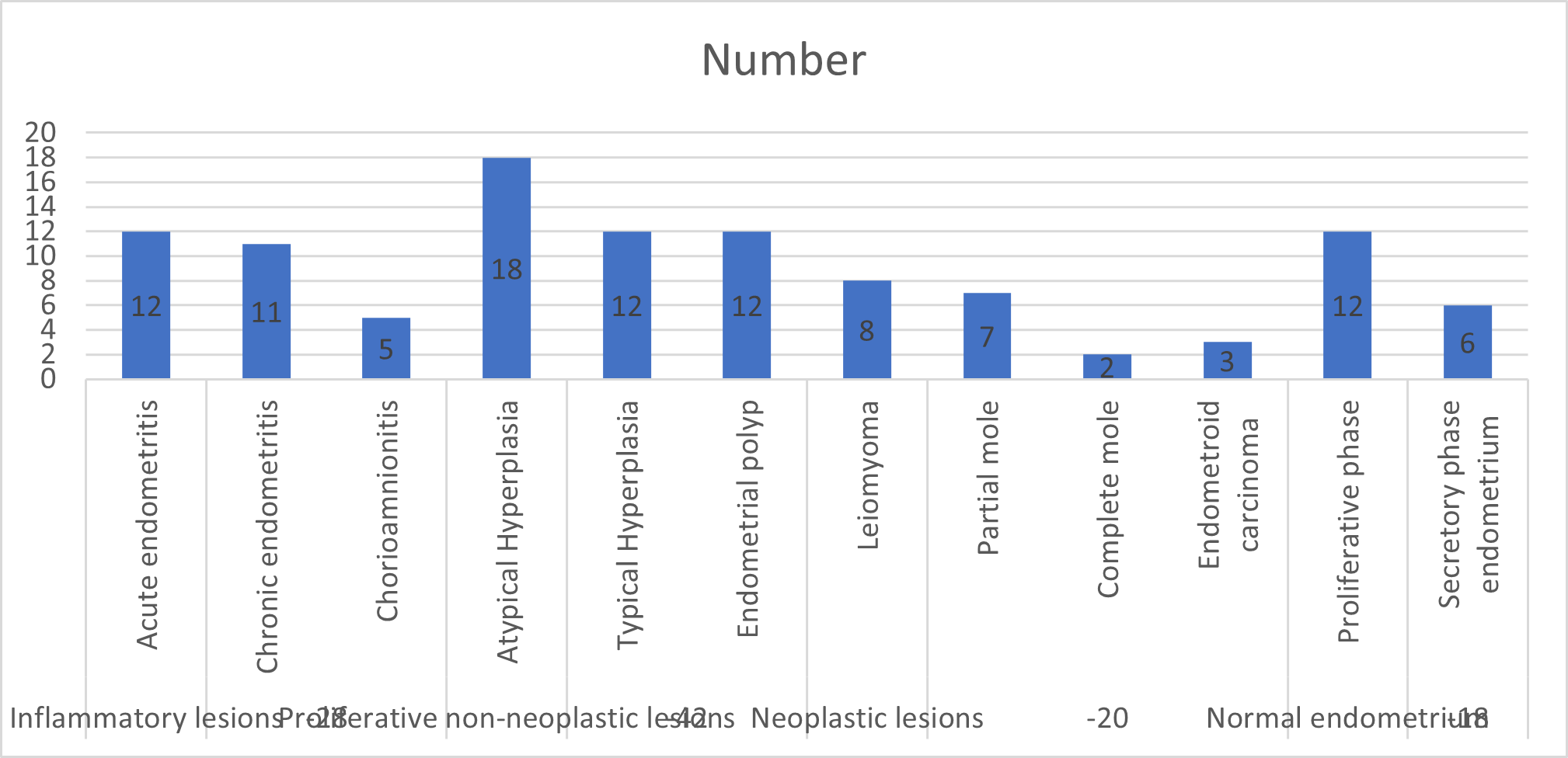

Results: The age group 20-30 years had 48, 30-40 years had 50, and 40-50 years had ten females. A significant difference was observed. Inflammatory lesions were 28, such as acute endometritis in 12, chronic endometritis in 11, and chorioamnionitis in 5. Proliferative non-neoplastic lesions were 42, such as atypical hyperplasia in 18, typical hyperplasia in 12, and endometrial polyp in 12. Neoplastic lesions in 20 include leiomyoma in 8, a partial mole in 7, the complete mole in 2, and endometroid carcinoma in 3. Normal endometrium in 18, such as proliferative phase in 12 and secretory phase endometrium in 6. A significant difference was observed (P< 0.05).

Conclusion: The most common endometrial biopsy revealed proliferative non-neoplastic lesions such as atypical hyperplasia, typical hyperplasia, and endometrial polyp.

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a commonly occurring gynecological complaint characterized by abnormal blood loss, duration of flow and frequency of menstruation [1]. It is evident among 30-35% of all females. The major outcome of AUB is anemia, which greatly impacts females’ health quality [2]. Among various causes of abnormal uterine bleeding, dysfunctional menometrorrhagia is a common one. To reach the diagnosis of AUB, a careful history as well as physical examination is required [3]. It is a challenging task among gynecologists. Transvaginal ultrasound may be helpful in up to 60% of cases, and the cause of the bleeding is recognized in only 50-60% of the cases. There can be various causes of AUB, such as physiological, pathological, or pharmacological [4,5].

It has been found to be linked with almost any type of endometrium, ranging from normal endometrium to hyperplasia, irregular ripening, chronic menstrual irregular shedding, and atrophy [6]. Histological variations of the endometrium are useful in detecting various disease patterns. It can be assessed with the help of the age of patients, the phase of the menstrual cycle, and iatrogenic use of hormones[7].

Histological variations of the endometrium can be detected, considering the woman’s age, the phase of her menstrual cycle, and iatrogenic use of hormones [8]. It is found that in about 10% of patients, endometrial cancer may be the outcome of abnormal perimenopausal or postmenopausal bleeding [9]. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia is the outcome of endometrial cancer and may progress over time to endometrial cancer in 5-25% of patients[10]. Considering this, we attempted present a study to assess histopathological patterns in the endometrial biopsy of patients presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding.

Demographic data of each patient was recorded. A detailed history of each patient was recorded. A thorough physical examination was performed. Pelvic ultrasound was performed. Dilatation and curettage were carried out. Specimens thus obtained were stored n 10% formalin. A gross study was done and multiple sections were obtained. The specimens were processed in automated tissue processor. Four to six-micron thick paraffin embedded sections were taken and stained by haematoxylin and eosin. The slides were examined under microscope and the various histopathological patterns assessed. Statistical assessment was carried using MS excel sheet with SPSS version 20.0. The level of significance was set below 0.05.

Age group 20-30 years had 48, 30-40 years had 50 and 40-50 years had 10 females. A significant difference was observed (P< 0.05) (Table 1, Figure 1).

| Age group (years) | Number | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 20-30 | 48 | 0.05 |

| 30-40 | 50 | |

| 40-50 | 10 |

Inflammatory lesions were 28, such as acute endometritis in 12, chronic endometritis in 11, and chorioamnionitis in 5. Proliferative non-neoplastic lesions were 42, such as atypical hyperplasia in 18, typical hyperplasia in 12, and endometrial polyp in 12. Neoplastic lesions in 20 include leiomyoma in 8, a partial mole in 7, a complete mole in 2, and endometroid carcinoma in 3.

Normal endometrium in 18, such as proliferative phase in 12 and secretory phase endometrium in 6. A significant difference was observed (P< 0.05) (Table 2, Figure 2).

| Parameters | Variables | Number |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory lesions (28) | Acute endometritis | 12 | <0.05 |

| Chronic endometritis | 11 | ||

| Chorioamnionitis | 5 | ||

| Proliferative non-neoplastic lesions (42) | Atypical Hyperplasia | 18 | >0.05 |

| Typical Hyperplasia | 12 | ||

| Endometrial polyp | 12 | ||

| Neoplastic lesions (20) | Leiomyoma | 8 | <0.05 |

| Partial mole | 7 | ||

| Complete mole | 2 | ||

| Endometroid carcinoma | 3 | ||

| Normal endometrium (18) | Proliferative phase | 12 | >0.05 |

| Secretory phase endometrium | 6 |

Our study showed that the age group 20-30 years had 48, 30-40 years had 50, and 40-50 years had ten females. Isuzu et al., [19] included 304 cases. Most of the cases of endometrial hyperplasia were typical. Endometritis and chorioamnionitis were the inflammatory conditions seen. It was seen that 23 females had molar pregnancies. The most common cause of abnormal uterine bleeding was retained products of conception.

We observed that inflammatory lesions were 28, such as acute endometritis in 12, chronic endometritis in 11, and chorioamnionitis in 5. Proliferative non-neoplastic lesions were 42, such as atypical hyperplasia in 18, typical hyperplasia in 12, and endometrial polyp in 12. Neoplastic lesions in 20 such as leiomyoma in 8, a partial mole in 7, a complete mole in 2, and endometroid carcinoma in 3. Normal endometrium in 18, such as proliferative phase in 12 and secretory phase endometrium in 6. Doraiswami et al., [20] found that 41-50 years was the most commonly involved age group with abnormal uterine bleeding seen in 33.5%. The most familiar pattern in these patients was normal cycling endometrium seen among 28.4%. The most familiar pathology was a disordered proliferative pattern seen in 20.5%. Other causes identified were complications of pregnancy (22.7%), benign endometrial polyp (11.2%), endometrial hyperplasias (6.1%), carcinomas (4.4%), and chronic endometritis (4.2%). Endometrial causes of AUB and age patterns were statistically significant.

Gunaken et al., [21] in their study, a total of 188 patients were included. The most common histopathological results were endometrial polyp was seen at 26.6%, atrophic endometrium at 22.3%, and surface epithelium at 12.8%. None of the 57 patients without vaginal bleeding had endometrial cancer. In 131 patients with vaginal bleeding, the mean endometrial thickness was 9.8 mm, and the rate of endometrial disorders was 56.5% (74 patients). Endometrial cancer was diagnosed in 19 patients (10.1%), and 36.8% of them had non-endometrioid cancers. The presence of vaginal bleeding was significantly associated with the diagnosis of endometrial cancer and any endometrial disorder.