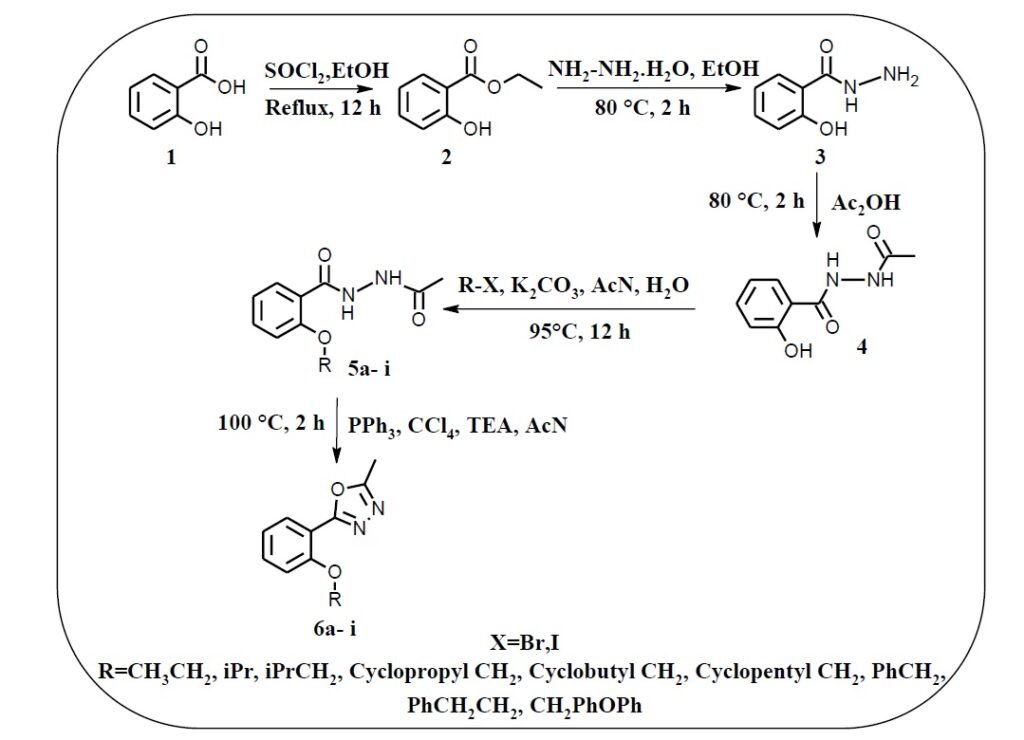

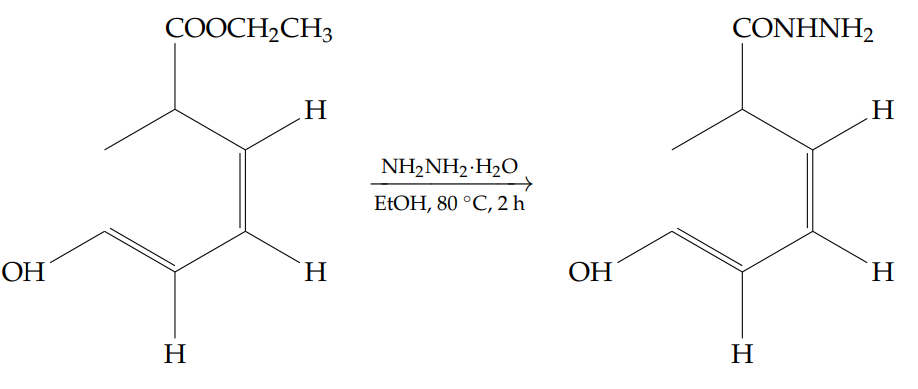

A series of novel 2-methyl-5-[2-(substituted)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives (6a–6i) was synthesized via a multi-step protocol starting from commercially available salicylic acid (1). The initial esterification of salicylic acid using thionyl chloride and ethanol at 80 °C for 12 h yielded ethyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (2), which was subsequently converted to 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide (3) upon treatment with hydrazine monohydrate in ethanol at 80 °C for 2 h. Acetylation of intermediate 3 with acetic anhydride afforded N’-acetyl-2-hydroxybenzoate (4), which was reacted with various halo compounds (4a–4i) to produce a series of N’-acetyl-2-(substituted)oxybenzohydrazides (5a–5i). These key intermediates were cyclized using triphenylphosphine, triethylamine, carbon tetrachloride, and acetonitrile at 100 °C for 1 h to furnish the final oxadiazole derivatives (6a–6i). The compounds were purified using appropriate chromatographic techniques and fully characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, FTIR, and mass spectrometry. Biological screening of the synthesized compounds revealed that several derivatives, particularly 6c, 6d, and 6g, exhibited promising antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Notably, compound 6a demonstrated significant cytotoxicity against HeLa cancer cells. Molecular docking studies further supported the biological potential of the compounds, with 6e displaying a high docking score of –5.66 kcal/mol.

The field of heterocyclic chemistry, which dates back to the 1800s [1], has grown into one of the most significant and expansive areas of organic chemistry. Following World War II, this discipline witnessed substantial development due to its crucial relevance in both chemical and biological sciences. Heterocyclic compounds—cyclic structures containing at least one heteroatom such as nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur—are fundamental components of numerous natural products and pharmaceuticals. These compounds are particularly important in cellular metabolism and are widely distributed in living organisms. Among heterocyclic systems, five- and six-membered rings are the most prevalent, with oxadiazoles, triazoles, and imidazoles attracting significant attention for their diverse biological and industrial applications.

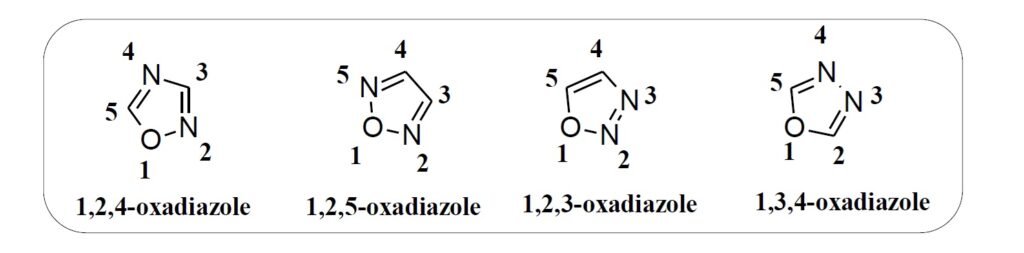

Oxadiazoles are a class of five-membered aromatic heterocycles composed of two carbon atoms, two nitrogen atoms, and one oxygen atom, with the general formula C2H2N2O. There are four isomeric forms of oxadiazoles based on the relative positions of nitrogen atoms in the ring: 1,2,3-oxadiazole, 1,2,4-oxadiazole, 1,2,5-oxadiazole, and 1,3,4-oxadiazole (Figure 1). Among these, the 1,3,4- and 1,2,4-isomers are the most widely studied due to their notable chemical stability and biological potential.

The 1,3,4-oxadiazole scaffold is particularly well known for its thermal stability and significant pharmacological relevance. The first compound of this class was synthesized by Anisworth in 1965 through thermolysis of ethyl formate and hydrazine at atmospheric pressure. Initially known by various common names such as furo(bb’)diazole, diazoxole, and biozole [2], the compound is now referred to by its IUPAC name: 1,3,4-oxadiazole.

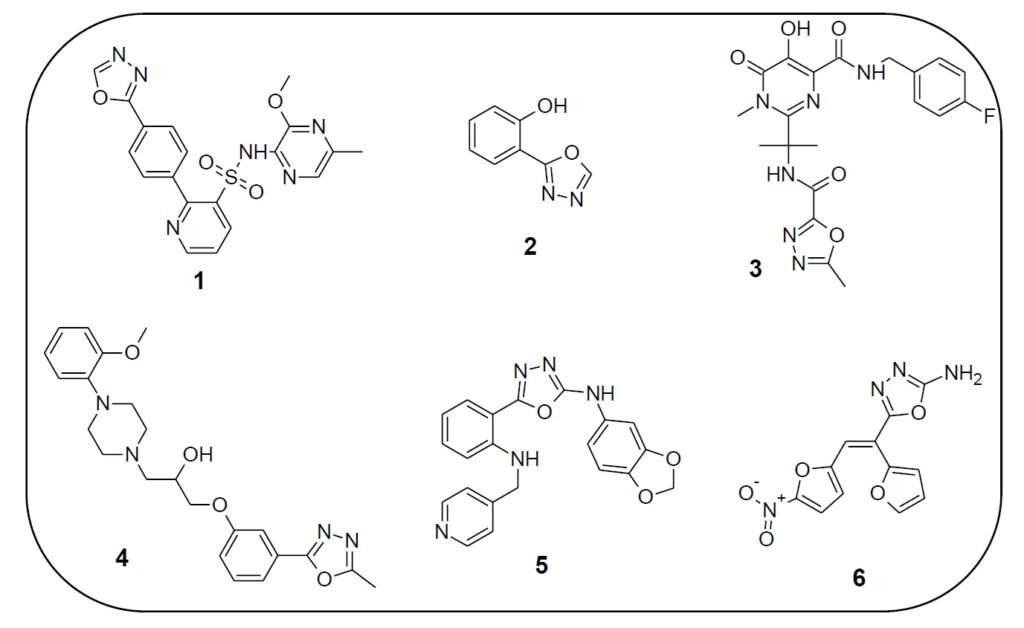

1,3,4-Oxadiazole derivatives exhibit a wide array of biological activities and are of considerable interest in both pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries. These compounds possess antibacterial [3], antifungal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antitubercular, anticonvulsant, anti-HIV [4], antihypertensive [5], antidiabetic, antitumor, antiviral, anesthetic, and antimalarial properties. Several oxadiazole-based drugs have reached clinical use. For instance, Zibotentan (1) is an anticancer agent, Fenadiazole (2) is a hypnotic drug, Raltegravir (3) is an antiretroviral, Nesapidil (4) acts as an antihypertensive, while ABT-751 (5) and Furamizole (6) are effective antibiotics (Figure 2).

In this study, we report the five-step synthesis of a new series of 2-methyl -5 -[2-(substituted)phenyl] -1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives, starting from salicylic acid. These compounds were obtained in good yields and were subsequently evaluated for their pharmacological properties (Figure 3).

All commercially available reagents and solvents were used without further purification unless otherwise stated. The Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using a Thermo Nicolet Avatar 370 spectrometer with a resolution of 1 cm-1, employing the KBr disk method to identify characteristic vibrational frequencies.

\(^1\)H and \(^{{13}}\)C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer. Deuterated solvents such as CDCl3, DMSO-d6, CD3OD, and D2O were used as appropriate. Chemical shifts (\(\delta\)) are reported in parts per million (ppm), and coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as the internal standard. The following abbreviations were used for multiplicity: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, dd = doublet of doublets, and m = multiplet.

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent 6460C Triple Quadrupole instrument to confirm the molecular weights and purity of all synthesized compounds.

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated at concentrations of 50, 100, 150, and 200 \(\mu\)g/mL in dimethylformamide against Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, using the Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) medium by the disc diffusion method [6].

Mueller-Hinton agar was prepared using the composition provided in Table 1. All ingredients were placed in a conical flask and heated on a steam bath to achieve a clear solution. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 \(\pm\) 0.2 and sterilization was performed by autoclaving at 15 lb pressure and 120 \(^\circ\)C for 15 minutes. The sterile medium was poured into Petri dishes and allowed to solidify. Test pathogens were uniformly spread onto the solidified medium. Wells of 6 mm diameter were created using a sterile cork borer and filled with the test solutions and standard drug. The plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37 \(^\circ\)C. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was recorded in millimetres as a measure of activity. Ciprofloxacin (20 \(\mu\)g/mL) was used as the standard antibiotic for comparison.

| Component | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Beef extract | 10.0 g |

| Casein acid hydrolysate | 17.5 g |

| Agar | 20.0 g |

| Starch | 1.5 g |

| Distilled water | 1000 mL |

The antifungal activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated at the same concentrations (50, 100, 150, and 200 \(\mu\)g/mL in dimethylformamide) against Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans, also using the disc diffusion method in MHA medium. The composition of the MHA used is identical to that in Table 1, and was prepared following the same procedure described above [7].

After spreading the fungal test organisms onto the MHA plates, 6 mm wells were made using a sterile cork borer and loaded with the test compounds and standard. Plates were incubated at 37 \(^\circ\)C for 24 hours. The inhibition zones (in mm) were recorded. Ciprofloxacin (20 \(\mu\)g/mL) was also used as the standard antibiotic to compare antifungal activity of the test compounds.

The DPPH assay procedure was followed as described in the literature [8]. An aliquot of 0.5 mL of the sample solution in methanol was mixed with 2.5 mL of 0.5 mM methanolic solution of DPPH. The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV spectrophotometer. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The DPPH free radical scavenging ability (%) was calculated using the following formula:

\[\% \text{ Of inhibition} = \left[\frac{\text{absorbance of control} – \text{absorbance of sample}}{\text{absorbance of control}}\right] \times 100.\]

In this analytical procedure, the measurements were conducted for five different concentrations of the samples along with one control. Each concentration was tested in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and accuracy in the assessment of DPPH radical scavenging activity.

The FRAP assay was performed in accordance with the reported method [9]. A volume of 100 \(\mu\)L of the sample (mg/mL) was added to 3 mL of freshly prepared FRAP reagent. The reaction mixture was incubated in a water bath for 30 min at 37 \(^\circ\)C. Absorbance was then measured at 593 nm. The difference between the absorbance of the sample and that of the blank was used to calculate the FRAP value. The FRAP value was expressed in terms of mmol Fe2+/g of sample, using a standard curve prepared with ferric chloride \((Y = 1.7057x – 0.2211, R^2 = 0.9904)\). All values were determined based on the average of three independent measurements.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was evaluated using the method described by Klein and colleagues [10]. Various concentrations of test compounds were taken in different test tubes and evaporated to dryness. To each tube, 1 mL of iron-EDTA solution (0.13% ferrous ammonium sulfate and 0.26% EDTA), 0.5 mL of EDTA (0.018%), and 1 mL of DMSO (0.85% v/v in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were added. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.5 mL of 0.22% ascorbic acid [5]. The tubes were tightly capped and heated in a water bath at 80 \(^\circ\)C to 90 \(^\circ\)C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 1 mL of ice-cold TCA (17.5% w/v). Then, 3 mL of Nash reagent (prepared from 75.0 g of ammonium acetate, 3 mL glacial acetic acid, and 2 mL acetyl acetone, diluted to 1 L with distilled water) was added. The tubes were left at room temperature for 15 min for color development. The yellow chromogen formed was measured at 412 nm against the reagent blank. Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and catechin were used as reference compounds. The percent inhibition was calculated using the following expression:

\[\text{Percent inhibition} = \left[1 – \left(\frac{\text{Control OD}}{\text{test OD}}\right)\right] \times 100.\]

The nitric oxide radical scavenging activity was evaluated as described by the Griess assay [11]. Sodium nitroprusside in aqueous solution at physiological pH produces nitric oxide, which reacts with oxygen to generate nitrite ions. These ions were detected using Griess reagent [6]. A reaction mixture of 3 mL containing 10 mM sodium nitroprusside in phosphate-buffered saline and the sample or standard compound was incubated at 25 \(^\circ\)C for 150 min. Every 30 min, a 0.5 mL aliquot was taken and mixed with 0.5 mL of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 2% H3PO4). The absorbance of the resulting chromophore was measured at 546 nm. Each test was performed in triplicate. Curcumin was used as a positive control. The percent inhibition of nitric oxide was calculated by comparing absorbance values of control and test samples using the formula:

\[\text{NO Scavenged (\%)} = \left[ \frac{(\text{A con} – \text{A test})}{\text{A con}} \right] \times 100.\]

where:

A con = Absorbance of the control reaction

A test = Absorbance in the presence of the sample

Cells (1 \(\times\) 105/well) were plated in 24-well plates and incubated in 37 \(^\circ\)C with 5% CO2 condition. After the cell reaches the confluence, the various concentrations of the compounds were added and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the compound was removed from the well and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) without serum. 100 \(\mu\)L/well (5 mg/mL) of 0.5% 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added and incubated for 4 h. After incubation, 1 mL of DMSO was added in all the wells. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a UV spectrophotometer using DMSO as the blank. Measurements were performed and the concentration required for a 50% inhibition (IC50) was determined graphically. The % cell viability was calculated using the following formula [12]:

\[\% \text{Cell viability} = \left( \frac{A570~\text{of treated cells}}{A570~\text{of control cells}} \right) \times 100.\]

Graphs are plotted using the % of Cell Viability at the Y-axis and concentration of the sample on the X-axis. Cell control and sample control are included in each assay to compare the full cell viability assessments.

Cells (1 \(\times\) 105/well) were plated in 24-well plates and incubated in 37 \(^\circ\)C with 5% CO2 condition. After the cell reaches the confluence, the various concentrations of the compounds were added and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the compound was removed from the well and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) without serum. 100 \(\mu\)L/well (5 mg/mL) of 0.5% 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added and incubated for 4 h. After incubation, 1 mL of DMSO was added in all the wells. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a UV spectrophotometer using DMSO as the blank. Measurements were performed and the concentration required for a 50% inhibition (IC50) was determined graphically. The % cell viability was calculated using the following formula [13]:

\[\% \text{Cell viability} = \left( \frac{A570~\text{of treated cells}}{A570~\text{of control cells}} \right) \times 100.\]

Graphs are plotted using the % of Cell Viability at the Y-axis and concentration of the sample on the X-axis. Cell control and sample control are included in each assay to compare the full cell viability assessments.

Molecular docking studies were carried out using AutoDock software. Docking of the macromolecule was performed using the Gibbs free energy function and the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm, with an initial population of 250 randomly placed individuals, a maximum number of 106 energy evaluations, a mutation rate of 0.02, and a crossover rate of 0.80. One hundred independent docking runs were performed for each ligand. Results differing by 2.0 Å in positional RMSD were clustered together and represented by the result with the most favorable free energy of binding. A lower binding energy value, a higher number of hydrogen bond formations, and a lower IC50 value determined the activity of the interacting compounds.

A stirred solution of salicylic acid (50 g, 0.316 mol) in ethanol (500 mL) was prepared and cooled to 0 \(^\circ\)C. Thionyl chloride[15] (100 mL, 1.376 mol) was added dropwise over 15 minutes. The mixture was then gradually heated to 80 \(^\circ\)C and stirred for 12 hours. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Upon completion, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to remove residual thionyl chloride and ethanol. The residue was diluted with water (250 mL) and extracted with methyl tert-butyl ether (2 \(\times\) 250 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield ethyl 2-hydroxybenzoate as a brown liquid (34.1 g, yield: 65%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.58\) (s, 1H, OH), 7.79 (d, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.51 (t, \(J = 8.0\) Hz, 1H), 6.93–7.00 (m, 2H), 4.37 (q, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 1.34 (t, \(J = 7.2\) Hz, 3H) ppm.

FT-IR (cm-1): 3189 (O–H, phenol), 2988, 1675 (C=O), 1614, 1480, 1300, 1249, 1216, 1091, 808, 756, 705.

A solution of ethyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (30 g, 0.180 mol) in ethanol (600 mL) was prepared, and hydrazine monohydrate[16] (150 mL) was added dropwise at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then heated to 80 \(^\circ\)C and stirred for 2 hours. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Upon completion of the starting material, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was added to ice-cold water (300 mL) and stirred for 30 minutes, during which a white precipitate formed. The solid was collected by filtration and dried to afford 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide as a white solid (19.3 g, yield: 70%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.10\) (s, 1H, OH), 7.78–7.81 (dd, \(J = 7.6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.36 (td, \(J = 7.6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 6.83–6.90 (m, 2H), 4.71 (s, 2H, NH2) ppm.

FT-IR (cm-1): 3274 (N–H, amide), 1652, 1530, 1372, 1304, 1245, 1146, 1033, 957, 756.

A mixture of 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide (18.0 g, 0.117 mol) and acetic acid[17] (180 mL) was heated to 80 \(^\circ\)C and stirred for 2 hours. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon completion, the reaction mixture was poured into ice-cold water (1.0 L) and stirred for 30 minutes until a white precipitate formed. The solid was collected by filtration and dried to afford the product as a white solid (12.8 g, yield: 56%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 11.89\) (s, 1H, OH), 10.52 (d, \(J = 2\) Hz, NH), 10.15 (d, \(J = 2\) Hz, 1H, NH), 7.60–7.89 (dd, \(J = 8.0,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.45 (td, \(J = 8.2,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 6.91–6.97 (m, 2H), 1.95 (s, 3H, CH3) ppm.

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 167.8\), 166.6, 158.8, 133.9, 128.3, 119.0, 117.2, 114.6, 20.4 ppm.

FT-IR (cm-1): 3413 (O–H, phenol), 3318 (N–H, amide), 3040 (C–H, aromatic), 1672, 1634, 1529, 1492, 1456, 1367, 1302, 1232, 1162, 1100, 1019, 962, 786, 742.

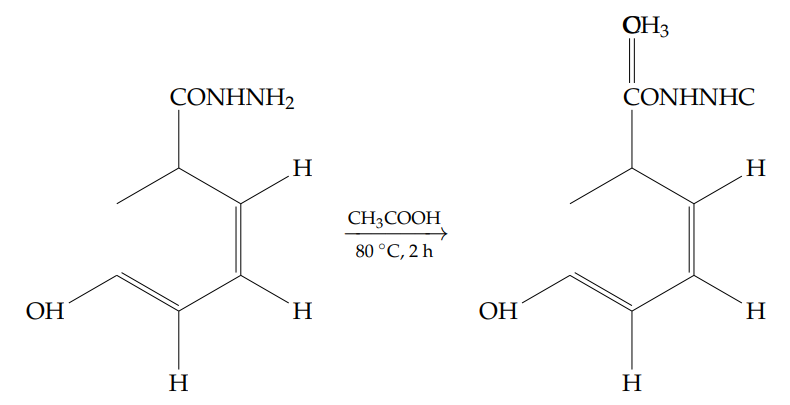

A stirred solution of N’-acetyl-2-hydroxybenzohydrazide (1.0 g, 0.0051 mol) in a 9:1 mixture of acetonitrile:water (10 mL) was treated with potassium carbonate [18] (1.64 g, 0.0128 mol) at room temperature and stirred for 15 minutes. Subsequently, the appropriate halide compound (0.0061 mol) was added. The mixture was then heated to 95 \(^\circ\)C and stirred for 12 hours. Reaction progress was monitored by TLC.

After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was diluted with water (10 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (2 \(\times\) 10 mL). The organic extracts were washed with water (10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated. The resulting semi-solid was suspended in hexane (10 mL), stirred at 0 \(^\circ\)C for 30 minutes, and the precipitate was filtered and dried to afford compounds 5a–5i.

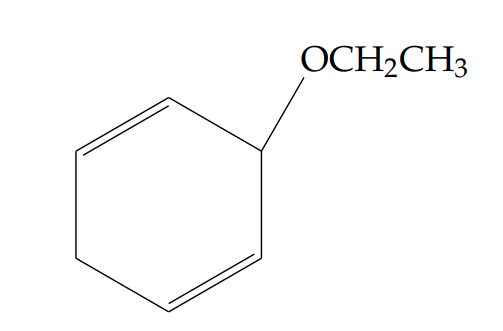

N’-acetyl-2-ethoxybenzohydrazide (5a): Yield 44%; obtained as an amorphous pink solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 11.10\)–11.08 (d, \(J = 8.0\) Hz, 1H, NH), 10.03–10.02 (d, \(J = 5.2\) Hz, 1H, NH), 8.20–8.18 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.45 (td, \(J = 6.8,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.06 (t, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.01–6.98 (d, \(J = 8.4\) Hz, 1H), 4.28–4.23 (q, \(J = 7.2,\ 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 1.67–1.63 (t, \(J = 7.2,\ 6.8\) Hz, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.0\), 159.9, 157.1, 133.5, 131.8, 121.2, 118.6, 112.2, 65.2, 20.6, 14.7.

LC-MS (m/z): 223.2 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3448, 3318, 3213, 2983, 2846, 1623, 1565, 1476, 1291, 1244, 1167, 1123, 1034, 745, 599.

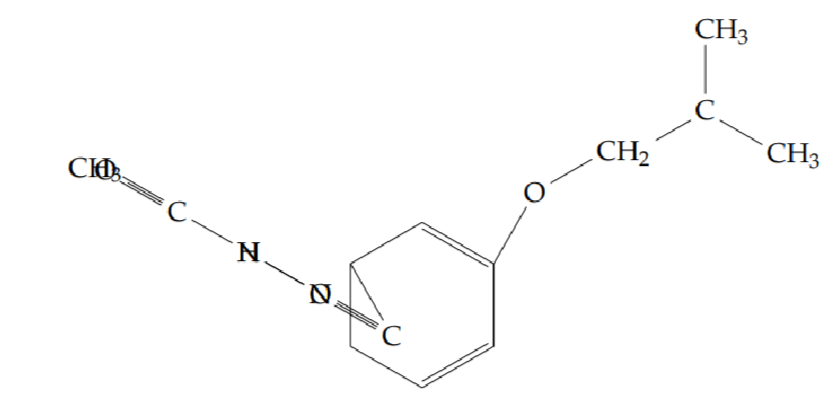

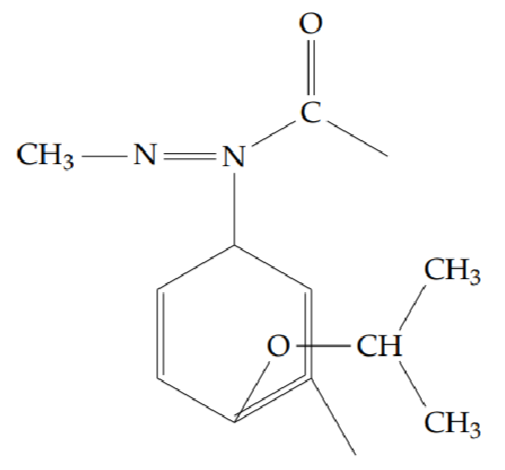

N’-acetyl-2-(propan-2-yloxy)benzohydrazide (5b): Yield 42%; obtained as a pale pink solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 11.26\) (s, 1H, NH), 10.60 (br, 1H, NH), 8.19–8.18 (dd, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.44 (t, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.07–7.00 (m, 2H), 4.84–4.81 (t, \(J = 6.8,\ 6.0\) Hz, 1H), 2.17 (s, 3H), 1.54–1.52 (d, \(J = 5.6\) Hz, 6H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.1\), 159.8, 156.0, 133.3, 131.9, 121.0, 119.5, 113.6, 72.4, 21.9, 20.5.

LC-MS (m/z): 237.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3311, 3282, 3227, 2977, 2931, 1615, 1562, 1473, 1387, 1244, 1159, 1142, 1045, 943, 760, 552.

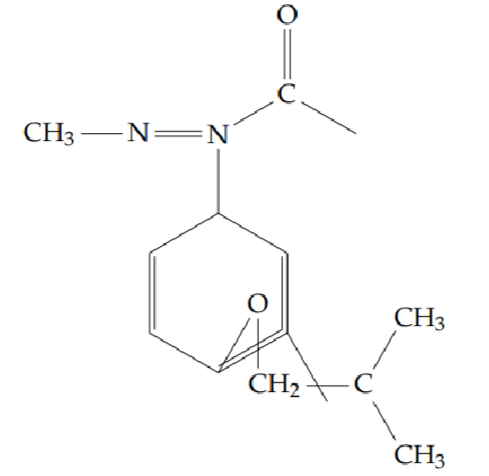

N’-acetyl-2-(2-methylpropoxy)benzohydrazide (5c): Yield 39%; obtained as a brown solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.97\) (s, 1H, NH), 10.13 (br, 1H, NH), 8.21–8.18 (t, \(J = 6.8,\ 0.8\) Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.45 (p, \(J = 7.2,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.06 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.01–6.99 (d, \(J = 8.4\) Hz, 1H), 3.95–3.93 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 2H), 2.42–2.35 (p, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 1H), 2.16 (s, 3H), 1.13–1.11 (d, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 6H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.0\), 160.1, 157.3, 133.5, 131.9, 121.1, 118.6, 112.2, 73.9, 34.1, 25.0, 20.7, 18.5.

LC-MS (m/z): 251.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3341, 3176, 3074, 2962, 2871, 1605, 1474, 1283, 1236, 1110, 1011, 770, 5.

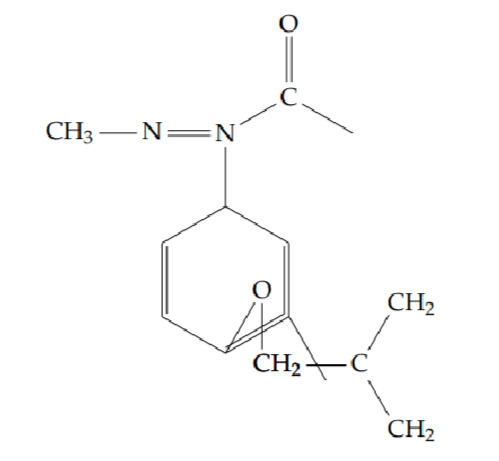

N’-acetyl-2-(cyclopropylmethoxy)benzohydrazide (5d): Yield 42%; obtained as a white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.43\) (s, 1H, NH), 10.15 (s, 1H, NH), 7.81–7.83 (d, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.51 (td, \(J = 7.2,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.04–7.16 (m, 2H), 4.02 (d, \(J = 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 1.28–1.34 (m, 1H), 0.55–0.60 (m, 4H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 166.8\), 162.6, 156.4, 132.8, 130.6, 120.9, 113.5, 73.2, 20.3, 9.9, 3.1.

LC-MS (m/z): 249 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3316 (N–H, amide), 3215 (N–H, amide), 3001, 2876, 1614, 1561, 1477, 1233, 1162, 1110, 986, 846, 745, 706.

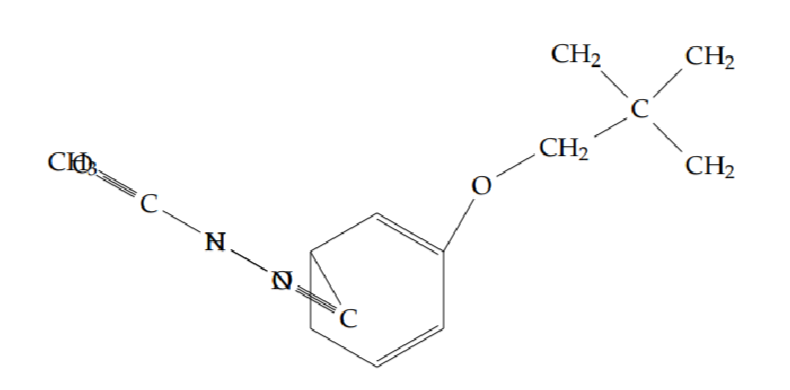

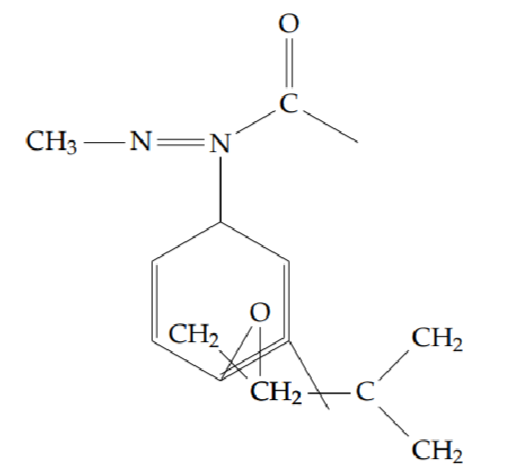

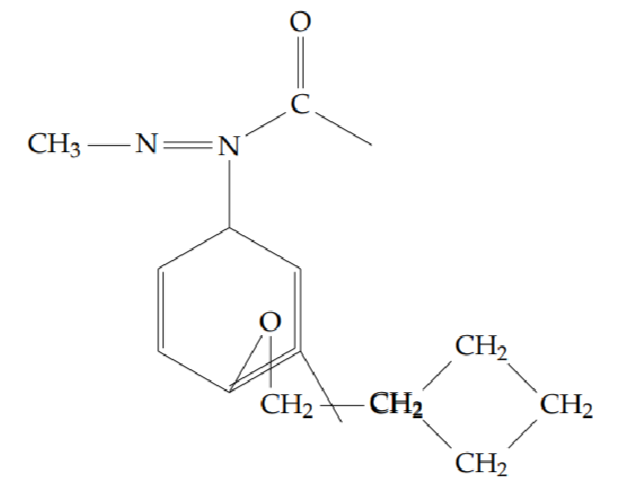

N’-acetyl-2-(cyclobutylmethoxy)benzohydrazide (5e): Yield 40%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.88\) (s, 1H, NH), 9.89 (s, 1H, NH), 8.20–8.18 (dd, \(J = 6.8,\ 0.8\) Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.45 (q, \(J = 7.2,\ 6.8\) Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.06 (t, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.01–6.99 (d, \(J = 8.4\) Hz, 1H), 4.16–4.14 (d, \(J = 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 3.07–3.00 (p, \(J = 8.4,\ 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.10–2.03 (m, 1H), 1.97–1.94 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.85 (m, 2H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.0\), 160.1, 157.3, 133.5, 131.9, 121.1, 118.6, 112.2, 73.9, 34.1, 25.0, 20.7, 18.5.

LC-MS (m/z): 263.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3321 (N–H, amide), 3227 (N–H, amide), 2967, 2937, 1624, 1567, 1476, 1264, 1166, 1119, 1003, 756, 599.

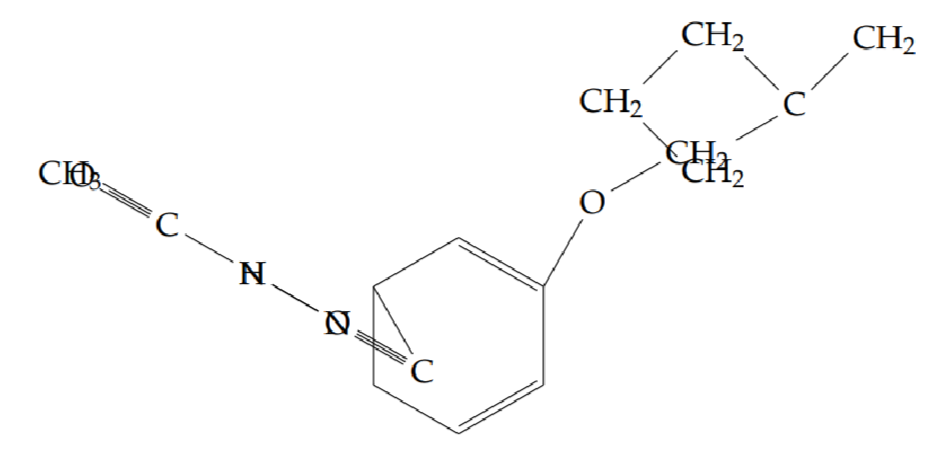

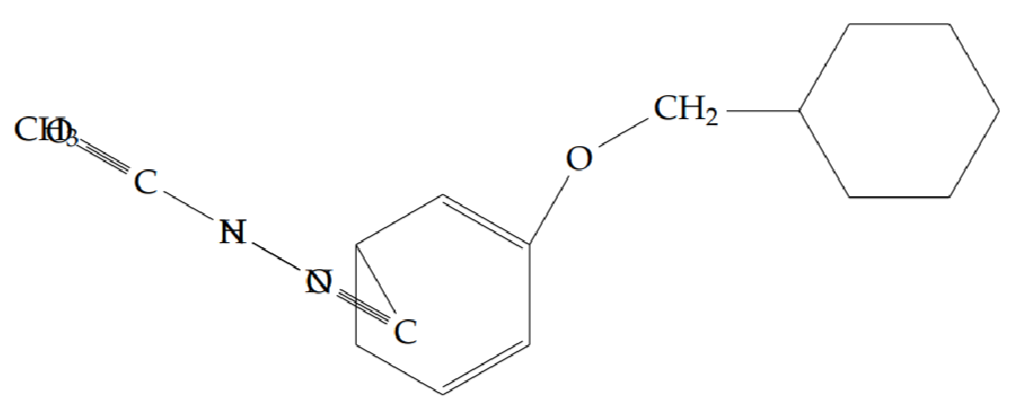

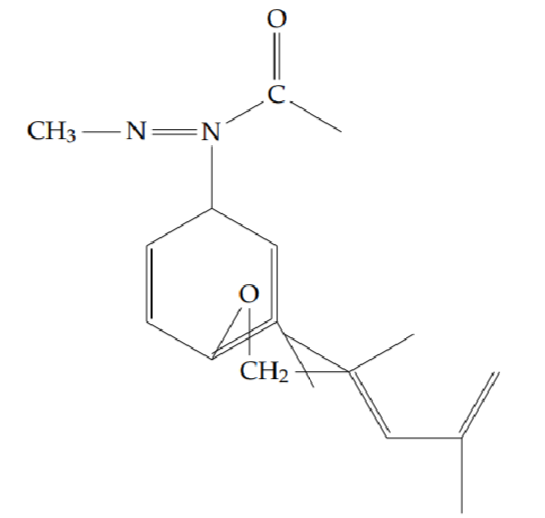

N’-acetyl-2-(cyclopentylmethoxy)benzohydrazide (5f): Yield 44%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.90\) (s, 1H, NH), 9.40 (s, 1H, NH), 8.21–8.19 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.44 (p, \(J = 6.8,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.06 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.01–6.99 (d, \(J = 8.4\) Hz, 1H), 4.04–4.02 (d, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 2H), 2.68–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.02–1.97 (q, \(J = 7.6,\ 5.2\) Hz, 2H), 1.67–1.64 (p, \(J = 3.6\) Hz, 4H), 1.41–1.34 (m, 2H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.1\), 160.3, 157.3, 133.5, 131.9, 121.1, 118.5, 112.2, 74.0, 38.7, 29.7, 25.5, 20.7.

LC-MS (m/z): 277.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3334 (N–H, amide), 3224 (N–H, amide), 2951, 2867, 1618, 1566, 1473, 1290, 1223, 1165, 1119, 1046, 755, 588.

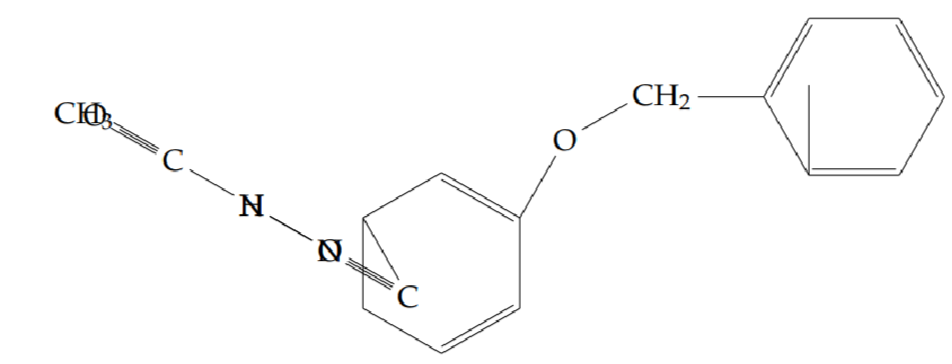

N’-acetyl-2-(benzyloxy)benzohydrazide (5g): Yield 55%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.67\)–10.65 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 1H, NH), 9.95–9.93 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 1H, NH), 8.18–8.16 (dd, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.47 (d, \(J = 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 7.45–7.40 (m, 3H), 7.38–7.30 (d, \(J = 8.4,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.09–7.03 (q, \(J = 8.4,\ 7.6\) Hz, 2H), 5.30 (s, 2H), 2.10 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 166.0\), 161.0, 156.7, 135.2, 133.5, 132.1, 128.9, 128.6, 127.7, 121.6, 119.3, 113.1, 71.4, 20.7.

LC-MS (m/z): 284.9 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3323 (N–H, amide), 3228 (N–H, amide), 3064, 3029, 2938, 2879, 1953, 1922, 1623, 1562, 1476, 1265, 1229, 1155, 1115, 1045, 751, 702, 592, 558.

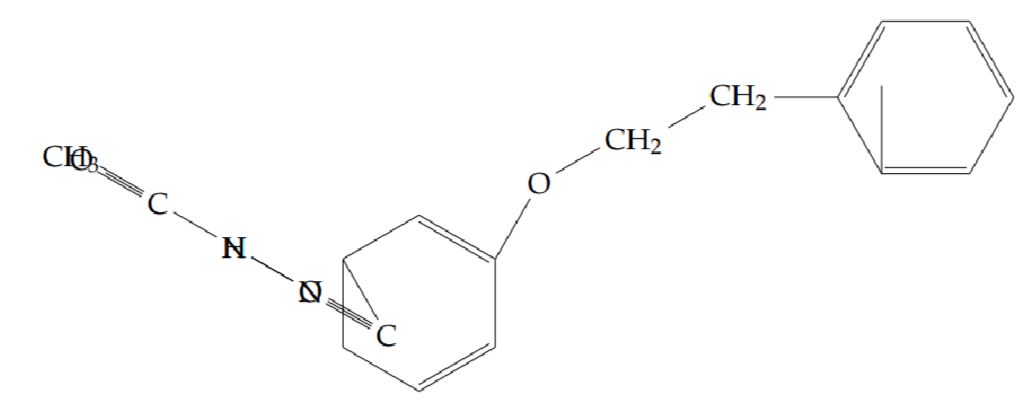

N’-acetyl-2-(2-phenylethoxy)benzohydrazide (5h): Yield 65%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.76\)–10.74 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 1H, NH), 9.77–9.76 (d, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 1H, NH), 8.19–8.16 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.43 (t, \(J = 6.4,\ 2\) Hz, 2H), 7.32–7.31 (d, \(J = 4.4\) Hz, 4H), 7.25 (s, 1H), 7.10–7.07 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 6.99–6.97 (d, \(J = 8.4\) Hz, 1H), 4.40–4.36 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 3.36–3.32 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 2.15 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.6\), 160.6, 156.8, 137.2, 133.6, 132.0, 128.9, 128.7, 128.1, 118.0, 112.4.

LC-MS (m/z): 299.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3321 (N–H, amide), 3225 (N–H, amide), 3072, 3031, 2934, 2878, 1621, 1563, 1478, 1274, 1234, 1164, 1113, 1005, 748, 699, 591.

N’-acetyl-2-[(4-phenoxybenzyl)oxy]benzohydrazide (5i): Yield 62%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 10.61\) (s, 1H, NH), 9.75–9.68 (br, 1H, NH), 8.18–8.16 (dd, \(J = 6.8,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.41 (t, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.30 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.22 (d, \(J = 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.01 (m, 3H), 6.99–6.96 (t, \(J = 9.2,\ 4\) Hz, 5H), 5.26 (s, 2H), 2.06 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta = 165.8\), 160.9, 157.7, 156.9, 156.5, 137.2, 133.5, 132.1, 130.3, 129.8, 129.7, 123.4, 122.4, 121.7, 119.3, 119.0, 118.8, 118.0, 113.1, 71.0, 20.6.

LC-MS (m/z): 377.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3318 (N–H, amide), 3215 (N–H, amide), 3052, 2887, 1946, 1673, 1622, 1488, 1253, 1212, 1162, 1115, 992, 747, 690, 597.

To a solution of corresponding N’-acetyl-2-substituted oxybenzohydrazides (0.0015 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 V) was added triphenylphosphine [19] (0.0015 mmol), triethylamine (5 V) and carbon tetrachloride (5 V) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was heated to 100 \(^\circ\)C and stirred for 2 h. The progressing of reaction mixture was monitored by TLC and it indicated that disappearance of starting material. The reaction mixture was concentrated to remove the solvent. The residue was diluted in water (10 V) and extracted with ethyl acetate (2 \(\times\) 5 V). The combined organic layer was washed with water (10 V) and saturated brine solution (10 V). The organic layer was dried over sodium sulphate and concentrated under reduced pressure to get corresponding Compounds 6a–6i crude materials. These crude compounds were purified by silica gel (100–200) column chromatography by eluting (15–20)% ethyl acetate in hexane to get corresponding final Compounds 6a–6i molecules.

2-(2-ethoxyphenyl)-5-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6a): Yield 43%; obtained as a yellow solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.90\)–7.87 (dd, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (td, \(J = 5.6,\ 2\) Hz, 1H), 7.05–7.01 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 1.2\) Hz, 2H), 4.19–4.14 (q, \(J = 7.2,\ 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 1.47–1.44 (t, \(J = 7.2,\ 6.8\) Hz, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 163.8\), 163.4, 157.1, 132.7, 130.4, 120.6, 113.5, 113.0, 64.5, 14.6, 11.0.

LC-MS (m/z): 205.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3421, 3058, 2930, 2869, 1594, 1533, 1455, 1385, 1255, 1121, 1019, 753, 698.

2-methyl-5-[2-(propan-2-yloxy)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6b): Yield 42%; obtained as a brown liquid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.90\)–7.88 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.42 (td, \(J = 7.2,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.04–7.01 (t, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 2H), 4.68–4.59 (m, 1H), 2.60 (s, 3H), 1.38–1.37 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 6H) ppm.

13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 164.0\), 163.5, 156.2, 132.6, 130.7, 120.7, 115.0, 114.6, 71.7, 22.0, 11.0.

LC-MS (m/z): 219.0 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3455, 2979, 2934, 1606, 1589, 1474, 1384, 1280, 1256, 1128, 1106, 1027, 948, 750, 708.

2-methyl-5-[2-(2-methylpropoxy)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6c): Yield 34%; obtained as a brown liquid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.94\)–7.92 (d, \(J = 7.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (td, \(J = 7.6,\ 0.8\) Hz, 1H), 7.05–6.99 (q, \(J = 8,\ 7.6\) Hz, 2H), 3.85–3.83 (d, \(J = 6\) Hz, 2H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.19–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.07–1.05 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 6H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 164.0\), 163.4, 157.2, 132.8, 130.4, 120.5, 113.4, 112.7, 75.0, 28.3, 19.1, 11.0.

LC-MS: 233.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3474, 3075, 2961, 2874, 1589, 1545, 1462, 1392, 1283, 1257, 1164, 1127, 1023, 959, 755, 709.

2-[2-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]-5-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6d): Yield 52%; obtained as an off-white solid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.93\)–7.90 (dd, \(J = 7.6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.42 (td, \(J = 8.0,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.07–7.00 (m, 2H), 3.99 (d, \(J = 6.4\) Hz, 2H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 1.33–1.23 (m, 1H), 0.62–0.46 (m, 4H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 163.9\), 163.5, 157.1, 132.7, 130.5, 120.8, 113.7, 73.2, 11.0, 10.1, 3.0.

LC-MS: 231 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3069, 3003, 2929, 2867, 1592, 1534, 1466, 1403, 1349, 1287, 1251, 1167, 1120, 1000, 761, 703.

Anal. Calcd. for C13H14N2O2: C, 67.81; H, 6.13; N, 12.17. Found: C, 67.11; H, 6.06; N, 12.03.

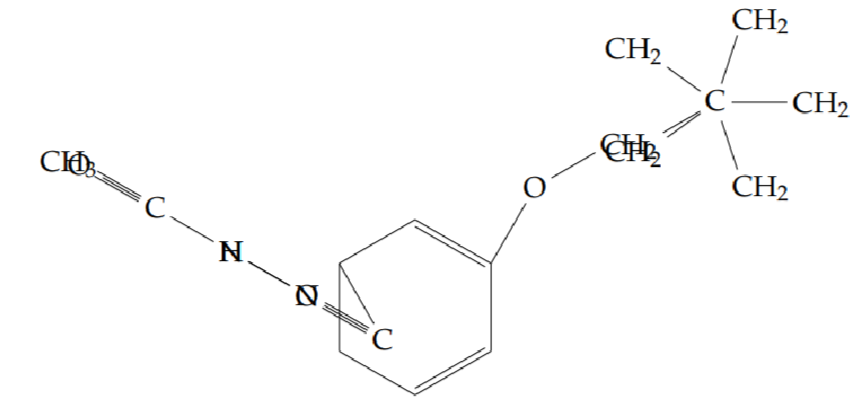

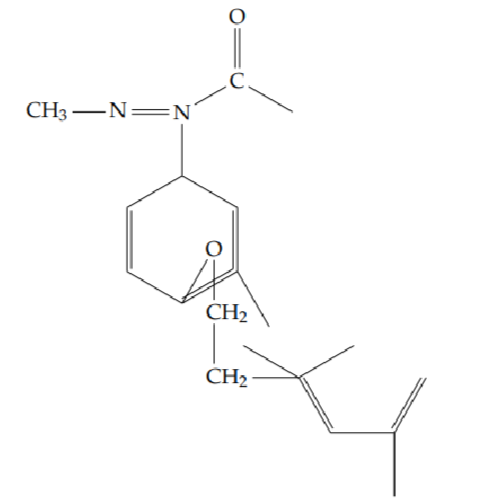

2-[2-(cyclobutylmethoxy)phenyl]-5-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6e): Yield 50%; obtained as a brown liquid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.95\)–7.92 (dd, \(J = 6,\ 2\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (td, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.05–7.00 (q, \(J = 6.8,\ 0.8\) Hz, 2H), 4.03–4.02 (d, \(J = 5.6\) Hz, 2H), 2.85–2.78 (m, 1H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.12–2.07 (m, 2H), 2.01–1.95 (m, 3H), 1.93–1.89 (m, 1H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 157.3\), 133.4, 130.5, 126.4, 120.6, 113.5, 112.8, 72.7, 39.09, 29.33, 25.55, 11.06.

LC-MS: 245.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3443, 2966, 2938, 2865, 1638, 1545, 1465, 1386, 1251, 1124, 998, 756.

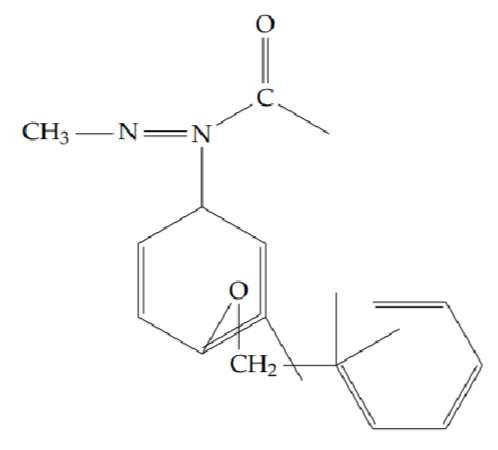

2-[2-(cyclopentylmethoxy)phenyl]-5-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6f): Yield 48%; obtained as a white solid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.93\)–7.91 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (td, \(J = 6.8,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.05–6.99 (m, 2H), 3.97–3.95 (d, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 2.85–2.78 (m, 1H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.45–2.37 (p, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 1.86–1.80 (p, \(J = 6.4,\ 6\) Hz, 2H), 1.67–1.57 (m, 4H), 1.44–1.39 (p, \(J = 7.2,\ 4.8\) Hz, 2H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 164.1\), 157.3, 132.8, 130.5, 120.6, 113.6, 113.1, 72.4, 42.3, 34.7, 24.5, 18.4, 13.2, 11.0.

LC-MS: 259.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3420, 3227, 2950, 2865, 1615, 1457, 1252, 1025, 756.

2-[2-(benzyloxy)phenyl]-5-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6g): Yield 45%; obtained as a yellow solid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.96\)–7.94 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.47 (td, \(J = 7.2,\ 1.6\) Hz, 2H), 7.45–7.43 (dd, \(J = 6.8,\ 0.8\) Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.36 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 2H), 7.33–7.29 (t, \(J = 7.6,\ 7.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.09–7.05 (t, \(J = 8,\ 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 2.58 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 163.5\), 156.6, 136.5, 132.8, 130.5, 128.5, 127.8, 126.8, 121.1, 113.8, 113.6, 70.6, 11.0.

LC-MS: 267.2 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3451, 3063, 3033, 2922, 2869, 1673, 1594, 1543, 1490, 1451, 1384, 1286, 1253, 1126, 1022, 745, 702.

2-methyl-5-[2-(2-phenylethoxy)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6h): Yield 46%; obtained as a yellow solid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.91\)–7.89 (dd, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.42 (td, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.24 (dd, \(J = 4.8\) Hz, 4H), 7.23–7.22 (t, \(J = 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.06–6.99 (qd, \(J = 6.8,\ 0.8\) Hz, 2H), 4.32–4.28 (t, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 3.17–3.14 (t, \(J = 6.8\) Hz, 2H), 2.57 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 163.8\), 163.5, 156.9, 138.0, 132.8, 130.6, 129.0, 128.4, 126.5, 120.8, 113.6, 112.9, 69.6, 35.6, 11.0.

LC-MS: 281.2 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3447, 2928, 2931, 2883, 1595, 1539, 1456, 1394, 1344, 1285, 1252, 1131, 1034, 917, 760, 703.

2-methyl-5-{2-[(4-phenoxybenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-1,3,4-oxadiazole (6i): Yield 45%; obtained as a yellow solid.

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 7.99\)–7.96 (dd, \(J = 6.4,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.44 (td, \(J = 6,\ 1.6\) Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.32 (q, \(J = 6.4,\ 0.8\) Hz, 3H), 7.25–7.22 (t, \(J = 8,\ 4\) Hz, 2H), 7.11–7.05 (m, 3H), 7.00–6.97 (dd, \(J = 7.6,\ 1.2\) Hz, 2H), 6.94–6.92 (d, \(J = 7.2,\ 1.2\) Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 2.54 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3-d6): \(\delta = 163.7\), 163.6, 157.4, 157.1, 156.4, 138.6, 132.8, 130.6, 129.9, 129.8, 123.3, 121.5, 121.3, 118.7, 117.4, 113.8, 113.5, 70.4, 10.9.

LC-MS: 359.1 [M+H]+.

FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3502, 2048, 1535, 1485, 1447, 1380, 1247, 1159, 1128, 1023, 958.

The title compounds were synthesized according to the synthetic strategy illustrated in Scheme 1. Initially, 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide was obtained from salicylic acid via two steps: esterification using thionyl chloride, followed by hydrazinolysis. N’-acetyl-2-hydroxybenzohydrazide was then synthesized through an acylation reaction. The hydroxyl group was subsequently alkylated with appropriate halides to yield substituted benzohydrazide derivatives. Finally, an intramolecular dehydration–cyclization reaction using triphenylphosphine and triethylamine afforded the desired 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives in good yields. The structures of all synthesized intermediates and final compounds were confirmed using 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, FT-IR, and LC-MS techniques.

The antibacterial potential of the synthesized compounds (6a–6i) was evaluated against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains using the well diffusion method. Among the tested compounds, 6c and 6g displayed significant antibacterial activity, comparable to the standard drug ciprofloxacin. The enhanced activity may be attributed to the presence of isopropyl and benzyl moieties in the oxadiazole ring, which likely contribute to better interaction with bacterial targets. Compound 6d exhibited moderate activity, whereas 6a, 6b, and 6e demonstrated lower antibacterial activity in comparison with ciprofloxacin. Detailed antibacterial data are provided in Table 2.

| Sl. No. | Compound |

Concentration

(\(\mu\))g/well) |

Zone of Inhibition (mm) | |||

| Gram-positive | Gram-negative | |||||

| E. faecalis | S. aureus | E. coli | K. pneumoniae | |||

| Ciprofloxacin (standard) | 20 | 40 | 33 | 35 | 32 | |

All together examination was found that compounds 6a and 6d exhibited the good antifungal activity which was comparable with standard Ciprofloxacin. The reason for the better activity of 6a & 6d compound having ethyl and cyclopropyl structures in the oxadiazole ring may contribute to activity against the pathogens. The compounds like 6b, 6c, 6e, 6f and 6g were poor antifungal activity with compared to standard Ciprofloxacin (Table 3).

| Sl. No. | Compound | Concentration (\(\mu\))g/well) | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |

| A. niger | C. albicans | |||

| 1 | 6a | 50 | – | 9 |

| 100 | – | 10 | ||

| 150 | – | 11 | ||

| 200 | – | 12 | ||

| 2 | 6b | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| 3 | 6c | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | 11 | ||

| 4 | 6d | 50 | – | 9 |

| 100 | – | 11 | ||

| 150 | – | 12 | ||

| 200 | – | 13 | ||

| 5 | 6e | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| 6 | 6f | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| 7 | 6g | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| 8 | 6h | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| 9 | 6i | 50 | – | – |

| 100 | – | – | ||

| 150 | – | – | ||

| 200 | – | – | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | 20 | 39 | 34 | |

All the nine synthesized compounds (6a-6i) were screened for their possible in vitro antioxidant activity through different in vitro modules such as 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH), nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen peroxide (\(H_2O_2\)) free radical scavenging and ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) activity. Observed results indicated that, few of the tested compounds are significant in their antioxidant properties.

Among the compounds 6a to 6i, compound 6i founds to have excellent antioxidant activity by using DPPH method than other compounds with 200 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. This activity can be comparable with standard Ascorbic acid. The reason for the improved activity might be due to the presence of phenoxybenzyl group, supported the activity (Table 4).

With compare to all synthesized compounds from 6a to 6i, compound 6i exhibited the excellent antioxidant activity using hydrogen peroxide method than other compounds with respect to 250 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. This activity can be comparable with standard Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The presence of phenoxybenzyl group in the oxadizole ring could be improving the excellent antioxidant activity (Table 5).

| Sl. No. | Compound | Concentration (\(\mu\))g/mL) * | |||||

| 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | \(IC_50\)) | ||

| 1 | 6a | 22.57 | 34.18 | 42.87 | 55.91 | 62.96 | 182.5 ± 7.31 |

| 2 | 6b | 42.92 | 51.30 | 56.59 | 61.15 | 63.06 | 140.7 ± 15.50 |

| 3 | 6c | 6.20 | 17.64 | 24.00 | 30.68 | 39.74 | \(>\)250 |

| 4 | 6d | 34.60 | 38.79 | 43.08 | 45.94 | 53.84 | 207.1 ± 18.45 |

| 5 | 6e | 37.36 | 44.93 | 49.60 | 52.73 | 57.66 | 175.3 ± 16.45 |

| 6 | 6f | 25.91 | 33.54 | 41.75 | 51.19 | 63.69 | 187.8 ± 8.25 |

| 7 | 6g | 11.13 | 20.93 | 31.74 | 44.51 | 62.10 | 212.2 ± 3.27 |

| 8 | 6h | 11.28 | 20.61 | 25.91 | 39.11 | 53.20 | 256.37 ± 32.27 |

| 9 | 6i | 43.08 | 58.18 | 57.34 | 61.68 | 69.47 | 131.9 ± 13.78 |

| Standard (Ascorbic acid) | 27.49 | 41.07 | 49.15 | 67.30 | 86.36 | 23.11 ± 2.05 | |

| *Scavenging activity values were the means of three replicates | |||||||

| Sl. No. | Compound | Concentration (\(\mu\)g/mL) * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-8 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | IC\(_50\) | |

| 1 | 6a | 15.29 | 16.69 | 22.31 | 24.19 | 26.48 | \(>\)250 |

| 2 | 6b | 13.84 | 17.00 | 23.81 | 25.76 | 29.24 | \(>\)250 |

| 3 | 6c | 4.92 | 10.00 | 20.22 | 27.02 | 31.35 | \(>\)250 |

| 4 | 6d | 25.69 | 31.97 | 38.89 | 41.91 | 48.18 | 265.44 ± 19.83 |

| 5 | 6e | 20.67 | 24.69 | 28.10 | 30.23 | 31.25 | \(>\)250 |

| 6 | 6f | 24.49 | 28.17 | 32.94 | 41.53 | 42.31 | 264.2 ± 20.39 |

| 7 | 6g | 23.18 | 28.28 | 31.44 | 36.89 | 41.58 | 279.2 ± 22.27 |

| 8 | 6h | 24.24 | 30.15 | 40.28 | 46.34 | 49.13 | 257.34 ± 24.72 |

| 9 | 6i | 38.07 | 45.44 | 46.86 | 49.57 | 50.98 | 246.34 ± 18.90 |

| Standard | Concentration (\(\mu\)g/mL) | ||||||

| 10 | 20 | 40 | 50 | \(IC_50\) | |||

| 10 | (BHT) | 27.15 | 28.34 | 38.03 | 51.53 | 52.88 | 44.90 ± 6.22 |

| *Scavenging activity values were the means of three replicates. | |||||||

Among the all-synthesized compounds from 6a to 6i, compound 6i was denoted the excellent antioxidant activity using nitric oxide method with compare to other compounds with respect to 50 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. This activity result was closely matching with standard Curcumin value. The presence of phenoxybenzyl group in the oxadizole ring may be suspecting for improving the excellent antioxidant activity (Table 6).

Among all the compounds 6g and 6i have been represented the highest optical density values at 250 (\(\mu\)M) concentration of sample in the Ferric ion reducing antioxidant power method. The presence of benzyl and phenoxybenzyl groups in the oxadizole ring could be improving the excellent antioxidant activity. Compound 6i exhibited the excellent result in the all four types of antioxidant methods (Table 7).

In vitro cytotoxic activity of newly synthesized compounds (6a-6i) was measured by MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay against a panel of human cancer cell line namely human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and normal cell line (Vero).

In overall observation, the compound 6a exhibited the excellent activity against human cancer cell line with compare to all other compounds. This could be due to the presents of ethyl substitution on the phenoxy aromatic ring. The compound 6e & 6c expressed the good activity against normal cell line among the other compounds. This may be due to the presents of 2-methyl propyl group and methyl cyclopentyl groups on the phenoxy aromatic ring (Table 8).

| Sl. No. | Compound | Concentration (\(\mu\))g/mL) * | |||||

| 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | IC$$_50$$) | ||

| 1 | 6a | 19.50 | 26.51 | 33.20 | 41.42 | 46.40 | 267.23 ± 31.2 |

| 2 | 6b | 12.24 | 23.51 | 28.81 | 35.10 | 40.34 | \(>\)250 |

| 3 | 6c | 6.31 | 14.46 | 27.09 | 38.75 | 44.93 | 267.23 ± 21.11 |

| 4 | 6d | 7.20 | 14.27 | 22.11 | 27.34 | 40.91 | 283.6 ± 6.85 |

| 5 | 6e | 6.43 | 14.27 | 24.21 | 32.69 | 42.00 | 263.16 ± 11.18 |

| 6 | 6f | 7.96 | 15.48 | 26.19 | 33.78 | 46.84 | 256.9 ± 5.18 |

| 7 | 6g | 25.36 | 30.78 | 38.81 | 47.93 | 54.24 | 253.16 ± 24.32 |

| 8 | 6h | 25.24 | 29.76 | 40.34 | 47.22 | 55.38 | 218.4 ± 32.17 |

| 9 | 6i | 29.95 | 35.31 | 38.04 | 48.50 | 57.55 | 203.4 ± 12.45 |

| Standard | Concentration (\(\mu\))g/mL) | ||||||

| 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 50 | \(IC_50\)) | ||

| 10 | Curcumin | 3.91 | 11.26 | 44.91 | 53.99 | 65.41 | 36.52 ± 2.37 |

| Concentration (\(\mu\))M) | Compounds (OD)* | ||||||||

| 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 6f | 6g | 6h | 6i | |

| Control | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.062 |

| 50 | 0.608 | 0.633 | 0.664 | 0.652 | 0.736 | 0.708 | 0.820 | 0.790 | 0.861 |

| 100 | 0.652 | 0.694 | 0.686 | 0.674 | 0.785 | 0.741 | 0.871 | 0.811 | 0.888 |

| 150 | 0.693 | 0.708 | 0.728 | 0.685 | 0.822 | 0.793 | 0.909 | 0.851 | 0.915 |

| 200 | 0.739 | 0.760 | 0.778 | 0.741 | 0.869 | 0.830 | 0.951 | 0.891 | 0.941 |

| 250 | 0.778 | 0.804 | 0.796 | 0.808 | 0.911 | 0.889 | 0.985 | 0.904 | 0.978 |

| *Data expressed the means of three replicates (OD-optical density) | |||||||||

| Sl. No | Compound Code | HeLa (\(\mu\))g/mL) | Vero (\(\mu\))g/mL) |

| 1 | 6a | 41.96 | 835.55 |

| 2 | 6b | 331.18 | 670.76 |

| 3 | 6c | 189.33 | 162.65 |

| 4 | 6d | 398.75 | \(>\)1000 |

| 5 | 6e | 186.36 | 124.55 |

| 6 | 6h | 342.00 | \(>\)1000 |

| 7 | 6i | 404.68 | \(>\)1000 |

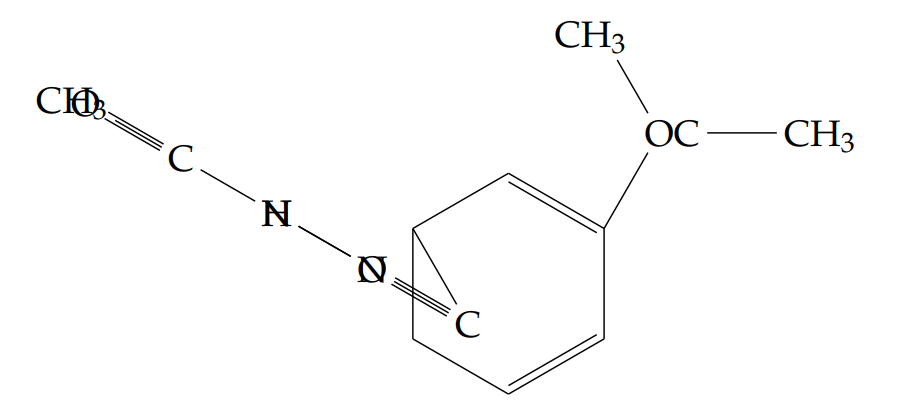

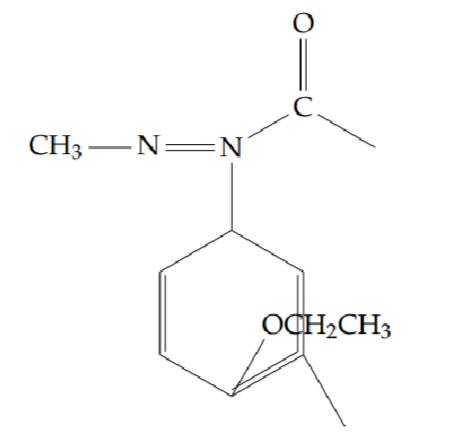

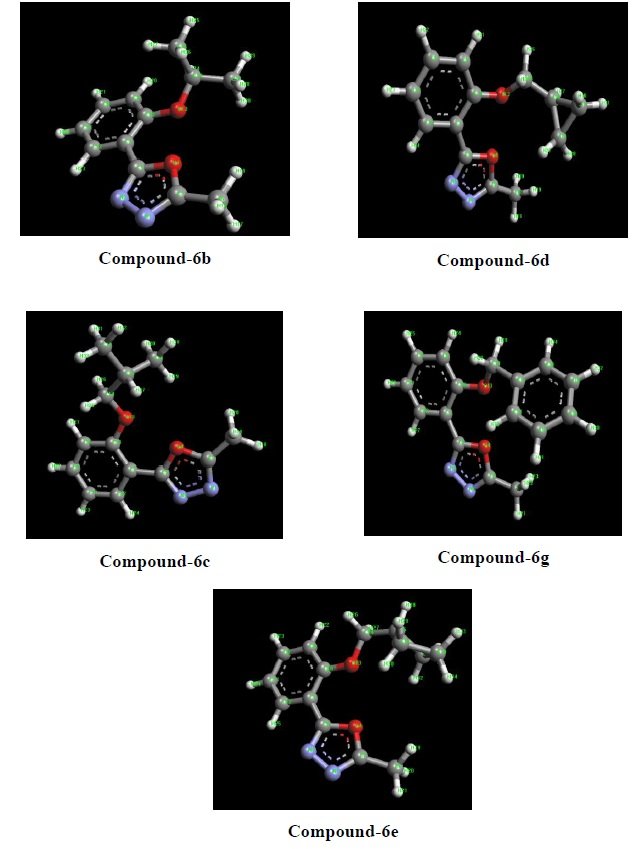

Docking simulation was performed to understand the interaction between the receptor and synthesized compounds (6a-6i). The results of the antibacterial and antifungal activities encouraged for docking studies. The compounds which can exhibit better antimicrobial activities were selected for docking using Autodock4.0 as software. Hence, compounds 6b, 6c, 6d, 6e and 6g (Figure 4) have been selected for docking against Escherichia coli protein. For Candida alibican protein binding, compounds 6a, 6c and 6d have been selected. Compounds 6c, 6d and 6g could be studied against Klebsiella pneumoniae protein. Similarly, compounds 6c and 6g can be opted for Enterococcus faecalis protein and compound 6g for Staphyococcus aureus protein.

Docking results were revealed that the docking score of compound 6e (-5.66 Kcal/mol) was found to be higher and compound 6d (-3.64 Kcal/mol) was represented the lowest against protein 3 – 4BJP (Table 9)

| Compounds |

Docking score/Binding

energy (K.cal/mol) |

Inhibitory constant

(KI) |

Hydrogen bonding interaction | Distance (Å) |

| 6b | -5.24 | 143.9 \(\mu\))M | LIG1: O – 4BJP:A:VAL302:O | 2.61 |

| LIG1:N – 4BJP:A:ASN533:ND2 | 3.23 | |||

| 6c | -4.36 | 638.11 \(\mu\))M | LIG1: O – 4BJP:A:VAL302:O | 2.35 |

| 6d | -3.64 | 2.15 \(\mu\))M | LIG1: N – 4BJP:A:VAL302:O | 2.12 |

| 6e | -5.66 | 70.89 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N – 4BJP:A:ASP301:OD2 | 2.46 |

| LIG1:N – 4BJP:A:SER259:OG | 3.45 | |||

| 6g | -3.76 | 1.76 \(\mu\))M | LIG1: N – 4BJP:A:VAL302:O | 3.24 |

The docking score of compound 6c (-7.33 Kcal/mol) was found to be higher and compound 6a (-6.82 Kcal/mol) was found to be lowest against protein 1NMT (Table 10).

| Compounds |

Docking score/Binding

energy (K.cal/mol) |

Inhibitory constant

(KI) |

Hydrogen bonding interaction | Distance (Å) |

| 6a | -6.82 | 10.0 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N – 1NMT:A:TYR335:OH | 2.86 |

| LIG1:N – 1NMT:A:TYR335:OH | 3.17 | |||

| 6c | -7.33 | 4.21 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:O – 1NMT:A:TYR335:OH | 2.97 |

| LIG1:O – 1NMT:A:LEU451:O | 2.91 | |||

| LIG1:N – 1NMT:A:TYR225:OH | 2.76 | |||

| 6d | -7.25 | 4.89 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N – 1NMT:A:LEU355:O | 2.80 |

| LIG1:O – 1NMT:A:LEU450:O | 3.13 |

The docking score of compound 6g (-8.96 Kcal/mol) exhibited the higher and compound 6c (-7.48 Kcal/mol) exhibited the lowest against protein 01 (Table 11).

| Compounds |

Docking score/Binding

energy (K.cal/mol) |

Inhibitory

constant (KI) |

Hydrogen bonding interaction | Distance (Å) |

| 6c | -7.48 | 3.29 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N–01:A:PRO111:O | 2.73 |

| LIG1:N–01:A:PRO111:O | 3.16 | |||

| 6d | -7.94 | 1.52 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:O–01:A:CYS113:O | 2.64 |

| 6g | -8.96 | 268.52 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N–01:A:PRO111:O | 2.87 |

| LIG1:N–01:A:PRO111:O | 3.81 |

The docking score of compound 6g (-7.54 Kcal/mol) was represented the higher and compound 6c (-6.33 Kcal/mol) was represented the lowest against protein 4M7V (Table 12).

| Compounds |

Docking score/Binding

energy (K.cal/mol) |

Inhibitory constant

(KI) |

Hydrogen bonding interaction | Distance (Å) |

| 6c | -6.33 | 22.97 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:O–4M7V:A:GLY97:O | 2.98 |

| LIG1:N–4M7V:A:ALA7:N | 3.26 | |||

| 6g | -7.54 | 2.99 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:O–4M7V:A:GLY97:O | 2.91 |

The docking score of compound 6g (-7.34 Kcal/mol) was observed well against protein 3SRW (Table 13).

| Compounds |

Docking score/Binding

energy (K.cal/mol) |

Inhibitory constant

(KI) |

Hydrogen bonding interaction | Distance (Å) |

| 6g | -7.34 | 4.14 \(\mu\))M | LIG1:N–3SRW:X:PHE93:O | 2.81 |

The present study describes the synthesis and characterization of novel 2-methyl-5-[2-(substituted) phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives. All intermediate compounds and final stage derivatives were confirmed by using the nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-NMR, 13C-NMR), LC-MS and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR).

All newly synthesized nine, 2-methyl-5-[2-(Substituted) phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives were screened with antibacterial activity against the test pathogen E. coli, E. faecalis, K. pneumonia, S. aureus and antifungal activity against the test pathogen A. niger, C. albicans. Compounds 6c, 6d and 6g were showed moderate antimicrobial activity with respect to the standard. Compounds 6a, 6b, and 6e have relatively lower antimicrobial activity. Except for the compounds 6f, 6h and 6i none of the compounds have showed the antimicrobial activity.

All the nine synthesized compounds (6a–6i) were screened for their possible in vitro antioxidant activity through different in vitro modules such as 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH), nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) free radical scavenging and ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) activity. Compound 6i was found to have excellent antioxidant activity by using DPPH method compared to other compounds at 200 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. Compound 6i also exhibited excellent antioxidant activity using the hydrogen peroxide method compared to other compounds at 250 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. Compound 6i was denoted as having excellent antioxidant activity using the nitric oxide method when compared to other compounds at 50 \(\mu\)g/mL concentration. Compounds 6g and 6i have shown the highest optical density values at 250 \(\mu\)M concentration of sample in the Ferric ion reducing antioxidant power method.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of newly synthesized compounds (6a–6i) was measured by MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay against a panel of human cancer cell line namely human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and normal cell line (Vero). The experimental results revealed that compound 6a showed remarkable inhibitory activity against human cancer cell line (HeLa) and compound 6e and 6c showed moderate viability activity against normal cell line (Vero).

Based on the antimicrobial result, different synthesized compounds (ligands) were docked with different proteins. Docking results revealed that the docking score of compounds 6e (-5.66 Kcal/mol) was found to be higher and compound 6d (-3.64 Kcal/mol) was found to be lowest against protein 3-4BJP. The docking score of compounds 6c (-7.33 Kcal/mol) was found to be higher and compound 6a (-6.82 Kcal/mol) was found to be lowest against protein 1NMT. Compound 6g (-8.96 Kcal/mol) exhibited the highest docking score and compound 6c (-7.48 Kcal/mol) expressed the lowest against protein 01. The docking score of compound 6g (-7.54 Kcal/mol) was represented the highest and compound 6c (-6.33 Kcal/mol) was indicated the lowest against protein 4M7V. The docking score of compound 6g (-7.34 Kcal/mol) was observed well against protein 3SRW.

Hossain, M., & Nanda, A. K. (2018). A review on heterocyclic: Synthesis and their application in medicinal chemistry of imidazole moiety. Science, 6(5), 83-94.

Khalilullah, H., J Ahsan, M., Hedaitullah, M., Khan, S., & Ahmed, B. (2012). 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole: a biologically active scaffold. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry, 12(8), 789-801.

Sudeesh, K., & Gururaja, R. (2017). Facile synthesis of some novel derivatives of 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole derivatives associated with quinolone moiety as cytotoxic and antibacterial agents. Organic Chemistry: Current Research, 6(2), 2-5.

Abbas, A., Nadeem, H., Khan, A. U., Ali, F., Afzaal, H., Nadhman, A., & Khan, I. (2017). Synthesis, Characterization, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic, Anticancer, Leishmanicidal, Anti-inflammatory Activities and Docking Studies of Heterocyclic 1, 3, 4-oxadiazoles and 4-amino-1, 2, 4-triazoles Derivatives. Journal of the Chemical Society of Pakistan, 39(4), 661-673.

Musmade, D. S., Pattan, S. R., & Manjunath, S. Y. (2015). Oxadiazole a nucleus with versatile biological behavior. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Analysis, 5, 11-20.

Pencheva, D. V., Ivancheva, K. S., Rumenkina, M. V., Al-Dzhasem, A. M., & Ivanov, I. N. (2018). In search of the truth about the quality of Mueller Hinton agar and tested antimicrobial discs. The Pharmaceutical and Chemical Journal, 5(1), 145–152.

Pfaller, M. A., Boyken, L., Messer, S. A., Hollis, R. J., & Diekema, D. J. (2004). Stability of Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with glucose and methylene blue for disk diffusion testing of fluconazole and voriconazole. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 42(3), 1288-1289.

Kedare, S. B., & Singh, R. P. (2011). Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 48, 412-422.

Vijayalakshmi, M., & Ruckmani, K. (2016). Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay in plant extract. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology, 11(3), 570-572.

Husain, S. R., Cillard, J., & Cillard, P. (1987). Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of flavonoids. Phytochemistry, 26(9), 2489-2491.

Banerjee, S., Chanda, A., Ghoshal, A., Debnath, R., Chakraborty, S., & Saha, R. (2011). Nitric Oxide scavenging activity study of ethanolic extracts of Ixora coccinea from two different areas of kolkata. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, 2(4), 595–599.

Tavares-Carreón, F., De la Torre-Zavala, S., Arocha-Garza, H. F., Souza, V., Galán-Wong, L. J., & Avilés-Arnaut, H. (2020). In vitro anticancer activity of methanolic extract of Granulocystopsis sp., a microalgae from an oligotrophic oasis in the Chihuahuan desert. PeerJ, 8, e8686.

Senthilraja, P., & Kathiresan, K. J. J. A. P. S. (2015). In vitro cytotoxicity MTT assay in Vero, HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines study of Marine Yeast. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 5(3), 080-084.

Kaboli, P. J., Ismail, P., & Ling, K. H. (2018). Molecular Docking-An easy protocol. IO, 1–8.

Omar, F. A., Mahfouz, N. M., & Rahman, M. A. (1996). Design, synthesis and antiinflammatory activity of some 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 31(10), 819-825.

Parameshwar, A., Selvam, V., Ghashang, M., & Guhanathan, S. (2017). Synthesis and antibacterial activity of 2-(2-(cyclopropylmethoxy) phenyl)-5-methyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole. Oriental Journal of Chemistry, 33(3), 1502-12.

De Oliveira, C. S., Lira, B. F., dos Santos Falcão-Silva, V., Siqueira-Junior, J. P., Barbosa-Filho, J. M., & de Athayde-Filho, P. F. (2012). Synthesis, molecular properties prediction, and anti-staphylococcal activity of N-acylhydrazones and new 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole derivatives. Molecules, 17(5), 5095-5107.

Mochona, B., Mazzio, E., Gangapurum, M., Mateeva, N., & Redda, K. (2015). Synthesis of some benzimidazole derivatives bearing 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole moiety as anticancer agents. Chemical Science Transactions, 4(2), 534–540.

Singh, R., & Chouhan, A. (2014). Various approaches for synthesis of 1, 3, 4-Oxadiazole derivatives and their pharmacological activity. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3(10), 1474-1505.