A series of novel substituted benzaldehyde derivatives of 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP), designated as compounds 1a–1d, were synthesized under microwave irradiation, providing a safe, cost-effective, and efficient alternative to conventional procedures. The condensation of 4A7HPP with hydroxybenzaldehyde analogues in DMF afforded the corresponding imine derivatives in high yields (71.54–85.02%) with reduced reaction time and solvent consumption. The synthesized compounds were characterized by 1H NMR, FT-IR, UV–Vis spectroscopy, and elemental analysis, confirming the presence of characteristic azomethine (–CH=N–) and aromatic proton signals. The compounds exhibited significant antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MIC: 7.5–28 mm), surpassing the standard drug streptomycin. Notably, antifungal evaluation against Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrated activity up to 2.5 times greater than fluconazole. Molecular docking studies performed against target proteins—S. aureus DHFR (PDB ID: 2W9H), E. coli DHFR (PDB ID: 1RX2), and C. albicans ERG11 (PDB ID: 5TZ1)—revealed stronger binding affinities for compounds 1b and 1d (−8.3 to −9.0 kcal mol−1) compared with reference ligands, supported by low RMSD values (0.655–0.785 Å). Brine shrimp lethality bioassay indicated moderate cytotoxicity (LD50: 3.50–8.50 × 10−4 M). ADME analysis suggested favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, high gastrointestinal absorption, and compliance with Lipinski’s rule of five. These results highlight compounds 1a–1d as potential lead molecules for the development of new antimicrobial and antifungal agents, warranting further biological and pharmacological investigations.

The existing literature highlights the regulatory and pharmacological importance of 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP). The persistent scientific interest in pyrrole derivatives as antimicrobial agents has motivated extensive research and development in this domain. Notably, compounds containing the 4A7HPP moiety have demonstrated significant antimicrobial potential [1].

Cancer remains one of the most critical global health concerns [2]. Derivatives of 4A7HPP have attracted the attention of organic and medicinal chemists owing to their diverse biological roles and promising chemotherapeutic applications [3]. Their fused heterocyclic analogues are also being actively explored for a wide range of biological activities. With the rapid rise of bacterial resistance to existing antimicrobial drugs, there is an urgent need to identify novel, more potent antibacterial agents. Microbial infections not only induce inflammation and weaken immune defense mechanisms but also contribute to disease progression, including cancer.

Globally, infections continue to represent a leading cause of mortality. According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 17,000 cancer-related deaths occur daily, posing an ever-growing challenge to healthcare systems worldwide [4, 5]. The COVID-19 pandemic further emphasized the necessity of discovering effective therapeutic agents, as the lack of viable treatments led to widespread morbidity and mortality.

Recent studies have shown that 4A7HPP-based compounds can inhibit the STAT6 protein, a key regulator in inflammatory signaling pathways. Consequently, STAT6 inhibitors are being explored for their potential in managing cancer, inflammatory diseases, and allergic disorders [6]. In parallel, advances in targeted therapy have revolutionized cancer treatment, offering enhanced efficacy with minimal side effects [7].

Purine analogues, such as 4A7HPP, have gained considerable importance due to their broad medicinal applications and biological significance [8, 9]. As a core component of DNA and RNA, the pyrimidine nucleus plays a fundamental role in biological systems, explaining the strong anticancer potential of pyrimidine-based compounds [10, 11]. Several clinically approved drugs—including ruxolitinib, tofacitinib, and baricitinib—incorporate the 4A7HPP scaffold and have demonstrated efficacy in cancer therapy [10]. Moreover, fused pyrrole systems, such as pyrrolopyrimidines and their derivatives, exhibit a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, particularly in oncology [12– 15].

The growing interest in 4A7HPP derivatives is attributed to their multifaceted therapeutic potential. These compounds have shown promising activity against microbial infections, cancer, inflammation, oxidative stress, viral diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders. Reported biological properties include enzyme inhibition [16], cytotoxicity [17], antiviral [18], anti-inflammatory [19– 21], antitumor [22, 23], and antimicrobial [24] activities.

This study focuses on the synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of a new series of 4A7HPP derivatives incorporating substituted hydroxybenzaldehydes. Pyrrolopyrimidine, a fused heterocyclic framework, represents a valuable scaffold in medicinal chemistry due to its broad spectrum of biological and therapeutic activities. Its unique structural features enable rational design and modification through structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies, leading to derivatives with enhanced potency, selectivity, and bioavailability. Consequently, pyrrolopyrimidine derivatives continue to play an important role in drug discovery and development.

Building upon this foundation, the present work reports the microwave-assisted synthesis and antibacterial screening of novel substituted benzaldehyde derivatives of 4A7HPP. Developing such biologically significant derivatives using green and efficient synthetic methodologies remains a central challenge in modern medicinal chemistry.

Microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) has gained significant attention as a modern, sustainable approach to chemical synthesis due to its high efficiency and eco-friendly characteristics [25– 29] Compared with conventional thermal methods, microwave irradiation dramatically reduces reaction times—often achieving rate enhancements of up to 200-fold under optimized conditions.

The rate of a microwave-assisted reaction is largely governed by the dielectric properties of the medium, with polar solvents exhibiting superior absorption of microwave energy compared to non-polar ones [30] As a low-frequency electromagnetic technique, microwave irradiation facilitates rapid, uniform heating, leading to shorter reaction times, higher product yields, reduced impurities, and improved energy efficiency [31– 35]

Thus, MAOS represents an environmentally benign and cost-effective alternative to traditional synthetic protocols, aligning well with the principles of green chemistry and the growing demand for sustainable practices in pharmaceutical research.

All raw materials were obtained from commercial sources and used without modification unless otherwise stated. High-purity compounds, including 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP), hydroxy benzaldehyde analogues, and solvents, were used in the synthesis. The target compounds were synthesized using both microwave irradiation and conventional techniques in DMF solvent. A Biotage Initiator microwave synthesis instrument was used in microwave synthesis, with internal temperature monitoring facilitated by an IR sensor. The reaction progress was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis employing silica gel (60 F254) plates.

The melting points of certain chemicals were not altered for accurate measurement. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra in the range of 4000–500 cm\(^{-1}\) were recorded using potassium bromide (KBr) pellets on a BRUKER FT-IR spectrophotometer. UV–Visible spectra were obtained using a JASCO V-650 spectrophotometer in methanol at ambient temperature. Using TMS as the internal reference standard, proton nuclear magnetic resonance (\(^1\)H NMR) spectra were acquired in deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d\(_6\)) at 400 MHz. The concentrations of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and nitrogen (N) were all within 0.4% of their theoretical levels. Summary statistics for the obtained chemicals are offered.

A solution of substituted benzaldehyde (2a–2d) (1.0 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (1.0 mmol) dissolved in DMF (5 volumes) was placed in a microwave reaction vessel and subjected to microwave irradiation at 100–150 W for 3 to 7 minutes. The progress of the reaction was periodically monitored by TLC using hexane and ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) as the mobile phase. Once the reaction was complete, the mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched with 10 volumes of water (relative to DMF). The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed twice with water (three volumes each time). The solid was then dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours. Subsequently, the dried material was refluxed in four volumes of ethanol and filtered at 0–5\(^\circ\)C. After filtration, the product was dried again at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for an additional 12 hours, and a series of compounds (1a–1d) was obtained (as presented in Table 1). The microwave-assisted synthesis achieved superior yields (80–92%) and significantly reduced reaction times compared to conventional reflux methods.

| Comp | Solvent | Microwave assisted | Conventional way | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp (\(^\circ\)C) | Time (min) | Yield (%) | Temp (\(^\circ\)C) | Time (h) | Yield (%) | ||

| 1a | IPA | 82 | 5 | 78.55 | 80–85 | 6 | 72.20 |

| Ethanol | 78 | 4 | 79.23 | 75–80 | 5 | 74.32 | |

| ACN | 82 | 6 | 72.21 | 78–82 | 10 | 69.94 | |

| DMF | 100 | 3 | 83.33 | 95–100 | 4 | 78.00 | |

| 1b | IPA | 82 | 6 | 77.10 | 80–85 | 6.5 | 71.15 |

| Ethanol | 78 | 5 | 75.15 | 75–80 | 4 | 70.88 | |

| ACN | 82 | 7 | 71.54 | 78–82 | 9 | 69.70 | |

| DMF | 100 | 4 | 82.54 | 95–100 | 3 | 75.80 | |

| 1c | IPA | 82 | 6 | 76.52 | 80–85 | 6 | 73.5 |

| Ethanol | 78 | 6 | 78.53 | 75–80 | 4 | 74.1 | |

| ACN | 82 | 7 | 74.13 | 78–82 | 10 | 70.21 | |

| DMF | 100 | 4 | 83.78 | 95–100 | 3.5 | 75.2 | |

| 1d | IPA | 82 | 5 | 71.81 | 80–85 | 4.5 | 70.3 |

| Ethanol | 78 | 4 | 73.43 | 75–80 | 4 | 71.5 | |

| ACN | 82 | 7 | 73.47 | 78–82 | 8.5 | 69.8 | |

| DMF | 100 | 3 | 85.02 | 95–100 | 3.5 | 73.45 | |

| – DMF 5 volume and benzaldehyde derivatives 1.0 equivalent. | |||||||

| – Reaction time (min.) is a reaction kept in microwave irradiation. | |||||||

| – Reaction time (h) is reaction mixture to heat on an oil bath/water bath. | |||||||

| – Yield (%) is isolated yield. | |||||||

| – All compounds were recrystallized in four volumes of ethanol to obtain the desired product. | |||||||

A mixture of substituted benzaldehyde (2a–2d) (1.0 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (1.0 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (10 volumes) and heated to reflux until the reaction was complete. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC, using hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) as the mobile phase. Once the reaction was finished, the mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched with 1 volume of water (relative to ethanol). The precipitate was filtered and washed twice with water (three volumes each). The solid was then dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours. The dried product was further refluxed in four volumes of ethanol for 3–4 hours and filtered at 0–5\(^\circ\)C. Afterward, the compound was dried again at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for an additional 12 hours, and a series of desired compounds (1a–1d) was obtained (as presented in Table 1). The reaction was also explored using various solvents, and experimental results indicated that DMF provided the highest yield and was the most suitable solvent for this transformation.

A solution of 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4.55 g, 0.0373 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (5.0 g, 0.0373 mmol) was dissolved in 25 mL of DMF and transferred to a microwave reaction vessel. The reaction mixture was irradiated with microwaves at 100–150 W for 3 minutes, with a temperature cycle of 100\(^\circ\)C for 30 seconds. The reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using a hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) mobile phase. Upon completion, the mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched by adding 250 mL of ice-cold water (10 volumes relative to DMF). The precipitate formed was filtered, washed twice with water (75 mL each), yielding a wet mass of 11.2 g. The solid was then dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours, giving a final yield of 8.1 g of compound 1a. The obtained compound was purified in ethanol to obtain 7.4 g of compound 1a (yield = 83.33%), as presented in Table 1.

Colour: light yellow; M.W.: 238.24; Yield: 83.33%; M.P.: 191\(^\circ\)C; Element content: C, 65.54; H, 4.23; N, 23.52; O, 6.72. FT-IR (cm\(^{-1}\)): 3201 (O–H), 2975 (N–H), 2922 (C–H), 1584/1482 (\(>\)C=C\(<\)), 1680 (\(>\)C=N–), 1302 (C–N), 762 (disubstituted benzene ring). \(^{1}\)H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): \(\delta\) 11.145 (Ar–NH), \(\delta\) 10.828 (Ar–OH), \(\delta\) 9.221 (–CH=), \(\delta\) 7.438–7.702 (aromatic amine) ppm. MS (EI): m/z calculated for [C\(_{13}\)H\(_{10}\)N\(_4\)O + H]: 238.24; found: 239.12. UV spectrum (\(\lambda\) nm): 298 (\(\pi\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)), 366 (\(n\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)).

A solution of 3-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4.55 g, 0.0373 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (5.0 g, 0.0373 mmol) was dissolved in 25 mL of DMF and transferred into a microwave reaction vessel. The reaction mixture was irradiated with microwaves at 100–150 W for 4 minutes, with a 30-second temperature cycle at 100\(^\circ\)C. The progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using a hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) mobile phase. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched with 250 mL of ice-cold water (10 volumes relative to DMF). The precipitate was filtered, washed twice with 75 mL of water each time, yielding a wet mass of 10.5 g. The solid was dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours, resulting in 7.89 g of compound 1b. Obtained compound purified in ethanol to obtain 7.33 g of 1b compound (yield = 82.54%), as presented in Table 1.

Colour: light yellow; M.W.: 238.24; Yield: 90%; M.P.: 199\(^\circ\)C; Element content: C, 65.54; H, 4.23; N, 23.52; O, 6.72. FT-IR (cm\(^{-1}\)): 3268 (O–H), 3134 (N–H), 2827 (C–H), 1590–1451 (\(>\)C=C\(<\)), 1657 (\(>\)C=N–), 1343 (C–N), 783 (disubstituted benzene ring). \(^{1}\)H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): \(\delta\) 11.145 (Ar–NH), \(\delta\) 10.828 (Ar–OH), \(\delta\) 9.231 (–CH=), \(\delta\) 7.438–7.702 (aromatic amine). MS (EI): m/z calculated for [C\(_{13}\)H\(_{10}\)N\(_4\)O + H]: 238.24; found: 239.22. UV spectrum (\(\lambda\) nm): 233 (\(\pi\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)), 327 (\(n\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)).

A solution of 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4.55 g, 0.0373 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (5.0 g, 0.0373 mmol) was dissolved in 25 mL of DMF and transferred into a microwave reaction vessel. The mixture was subjected to microwave irradiation at 100–150 W for 4 minutes, with a temperature cycle of 100\(^\circ\)C for 30 seconds. The progress of the reaction was tracked using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with a mobile phase composed of hexane and ethyl acetate in an 8:2 (v/v) ratio. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched by adding 250 mL of ice-cold water (10 volumes relative to DMF). The precipitated solid was filtered and washed twice with 75 mL of water each time, yielding a wet mass of 12.25 g. The solid was then dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours, yielding 8.12 g of dry compound 1c. Obtained compound purified in ethanol to obtain 7.44 g of 1c compound (yield = 82.54%), as presented in Table 1.

Colour: Yellow; M.W.: 238.24; Yield: 92%; M.P.: 198\(^\circ\)C; Element content: C, 65.54; H, 4.23; N, 23.52; O, 6.72. FT-IR (cm\(^{-1}\)): 3512.92 (O–H), 3198.54 (N–H), 3076.29 (C–H), 1570–1434 (\(>\)C=C\(<\)), 1662 (\(>\)C=N–), 1347 (C–N aromatic amine), 723 (disubstituted benzene ring). \(^{1}\)H NMR (400 MHz in DMSO): \(\delta\) 12.38 (Ar–NH), \(\delta\) 12.258 (Ar–OH), \(\delta\) 10.341 (–CH=), \(\delta\) 6.974–8.408 (aromatic amine). MS (EI): m/z calculated for [C\(_{13}\)H\(_{10}\)N\(_4\)O + H]: 238.24; found: 239.15. UV spectrum (\(\lambda\) nm): 267 (\(\pi\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)), 345 (\(n\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)).

A solution of 2-hydroxy-5-nitrobenzaldehyde (6.23 g, 0.0373 mmol) and 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo [2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) (5.0 g, 0.0373 mmol) was dissolved in 25 mL of DMF and placed in a microwave reaction vessel. The reaction mixture was irradiated with microwaves at 100–150 W for 3 minutes, with a temperature cycle of 100\(^\circ\)C for 30 seconds. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC), using a hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) mobile phase, was employed to monitor the reaction progress. Once the reaction reached completion, the mixture was cooled to 25–30\(^\circ\)C and quenched by adding 250 mL of ice-cold water (10 volumes relative to DMF). The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed twice with 75 mL of water each time, yielding a wet mass of 12.8 g. The solid was then dried in a tray dryer at 50–55\(^\circ\)C for 12 hours, yielding 8.1 g of dry compound 1d. Obtained compound purified in ethanol to obtain 7.55 g of 1d compound (Yield = 85.02%), as presented in Table 1.

Colour: Yellow; M.W.: 283.24; Yield (94%); M.P.: 201\(^\circ\)C; Element content: C, 55.13; H, 3.20; N, 24.73; O, 16.95. FT-IR (cm\(^{-1}\)): 3222 (O–H), 3062 (N–H), 2924 (C–H), 1589/1498 (\(>\)C=C\(<\)), 1677 (\(>\)C=N–), 1360 (C–N aromatic amine), 1360 (N–O symmetrical stretching), 1470 (N–O asymmetrical stretching), 818 (trisubstituted benzene ring). \(^{1}\)H NMR (400 MHz in DMSO): \(\delta\) 12.392 (Ar–NH), \(\delta\) 10.593 (Ar–OH), \(\delta\) 8.047 (–CH=), \(\delta\) 7.333–7.586 (aromatic amine). MS (EI): m/z calculated for [C\(_{13}\)H\(_9\)N\(_5\)O\(_3\) + H]: 283.24; found: 283.99. UV spectrum (\(\lambda\) nm): 263 (\(\pi\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)), 370 (\(n\rightarrow\pi^{*}\)).

The antibacterial activity of the synthesised compounds was evaluated using two gram-positive bacteria and two gram-negative bacteria. Muller–Hinton agar medium was autoclaved at 15 lbs/in\(^{2}\) for 15 minutes before use in antimicrobial testing. To determine whether the newly synthesized compounds exhibited antibacterial properties, researchers employed the disc diffusion technique [38]. The inoculum was diluted to a concentration of approximately \(10^{8}\) cfu/mL by floating the culture in sterile distilled water. Each microbial strain’s culture was swabbed into a Petri dish with 20 mL of Muller–Hinton agar medium and incubated for 15 minutes. Wells (6 mm in diameter) were drilled using a sterile borer, and 100 \(\mu\)L of a 4.0 mg/mL solution of each substance (1a–1d) was added to the infected plates. After 24 hours of incubation at 37 \(^\circ\)C, all of the plates were read. All synthetic compounds (1a–1d) were tested for their antibacterial activity by measuring the size of the zone of inhibition surrounding the wells. Streptomycin was used as a positive control, while DMF was used as a negative control.

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized compounds was assessed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) using the agar well diffusion method [39] Fresh microbial cultures were prepared and adjusted to approximately \(10^{8}\) cfu/mL. Muller–Hinton agar plates were inoculated uniformly with the microbial suspensions. Wells (6 mm diameter) were then made in the agar using a sterile borer. Different concentrations of the test compounds (1a–1d) were prepared, and 100 \(\mu\)L of each concentration was introduced into the corresponding wells. The plates were incubated at 37 \(^\circ\)C for 24 hours, after which the inhibition zones were measured. The MIC values were recorded as the lowest concentration of each compound that produced a visible zone of inhibition. Streptomycin served as the positive control, while DMF was used as the negative control.

The compounds were tested against two different types of fungi (C. albicans MCC1439 and S. cerevisiae MCC1033) using the cup-and-plate method [39, 40]. Micropipettes were used to pipette the test solution onto discs measuring 5 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness, and the plates were then incubated at 37 \(^\circ\)C for 72 hours. During this period, the test solutions (1a–1d) diffused across the medium and influenced the growth of the infected fungi. After 36 hours of incubation at 37 \(^\circ\)C, the size of the inhibitory zone was determined. Promising compounds showing antifungal activity had their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) determined. The MIC of an antifungal agent was defined as the lowest concentration at which visible inhibition of microbial growth occurred following a 24-hour incubation period. The MIC is commonly employed in clinical laboratories to confirm microbiological resistance to antimicrobials and to evaluate the efficacy of novel antimicrobials.

The cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds was tested using a bioassay with brine shrimp. Prawn egg fake seawater (38 g NaCl/1000 mL tap water) was supplied to the other side. The shrimp eggs hatched, and the nauplii developed over 48 hours. The newly hatched shrimp were collected for testing. Different concentrations (2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0, and 12.0 mg/10 mL) of dried complexes were placed in separate test tubes. The cytotoxic potential of the complexes was evaluated by dissolving DMSO in them. Each test tube included 10 living shrimp, which were transferred using a Pasteur pipette. To ensure the reliability of the cytotoxic activity (1a–1d) test and the results it produced, there was also a control group. After 24 hours of incubation, the tubes were examined under a microscope to observe the survival of the nauplii. The number of surviving nauplii was recorded. Each experiment included three duplicate sets for a total of five sets. Based on the data, we determined the LC\(_{50}\), 95% CI, LC\(_{90}\), and chi-square values. Abbott’s formula [41] was used to adjust for control mortality.

The drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties of compounds 1a–1d were assessed using the SwissADME web-based tool. Key physicochemical parameters, including molecular weight (MW), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), topological polar surface area (TPSA), lipophilicity (Log P), aqueous solubility (Log S), gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, Lipinski’s rule of five violations, bioavailability score, and synthetic accessibility, were calculated. The SwissADME reference ranges for drug-like molecules were used as benchmarks: MW \(< 500\) g/mol, HBA \(\le 10\), HBD \(\le 5\), TPSA \(\le 130\) Å\(^{2}\), Log P between \(-0.7\) and \(5\), Log S between \(-6\) and \(0\), and synthetic accessibility scores between \(1\) and \(10\). The computed parameters for compounds 1a–1d are summarized in Table 2.

The molecular weights of compounds 1a–1d ranged from 238.24 to 283.24 g/mol, well below the 500 g/mol threshold. The HBA (4–6) and HBD (2) values complied with Lipinski’s criteria (HBA \(\le 10\), HBD \(\le 5\)). TPSA values ranged from 74.16 to 119.98 Å\(^{2}\), indicating a favorable balance between polarity and membrane permeability. Log P values (1.5–2.1) suggested optimal lipophilicity, supporting efficient membrane permeation without compromising aqueous solubility. All compounds exhibited Log S values around \(-3.02\) to \(-3.04\), indicating good solubility, and were predicted to have high GI absorption, making them suitable for oral administration. No violations of Lipinski’s rule of five were observed, and all compounds had a bioavailability score of 0.55, indicating moderate oral bioavailability. Synthetic accessibility scores ranged from 2.50 to 2.73, suggesting that the compounds are synthetically feasible for further development.

Molecular docking studies were conducted to evaluate the binding affinity of compounds 1a–1d against selected bacterial and fungal protein targets. The docking simulations were performed using SwissADME, with protein structures retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The target proteins included dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) from Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive, PDB ID: 2W9H, resolution: 1.48 Å) and Escherichia coli (Gram-negative, PDB ID: 1RX2, resolution: 1.80 Å), as well as lanosterol 14\(\alpha\)-demethylase (ERG11) from Candida albicans (PDB ID: 5TZ1, resolution: 2.00 Å). The protein structures were prepared by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Gasteiger charges. Compounds 1a–1d were docked into the active sites of the target proteins, and their binding affinities (docking scores, expressed in kcal/mol) were compared with those of standard drugs: streptomycin (a broad-spectrum antibiotic for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria) and fluconazole (a standard antifungal drug). The results were analyzed to assess the potential antimicrobial activity of compounds 1a–1d based on their interactions with the target proteins. Selected protein structures for molecular docking studies are presented in Table 3.

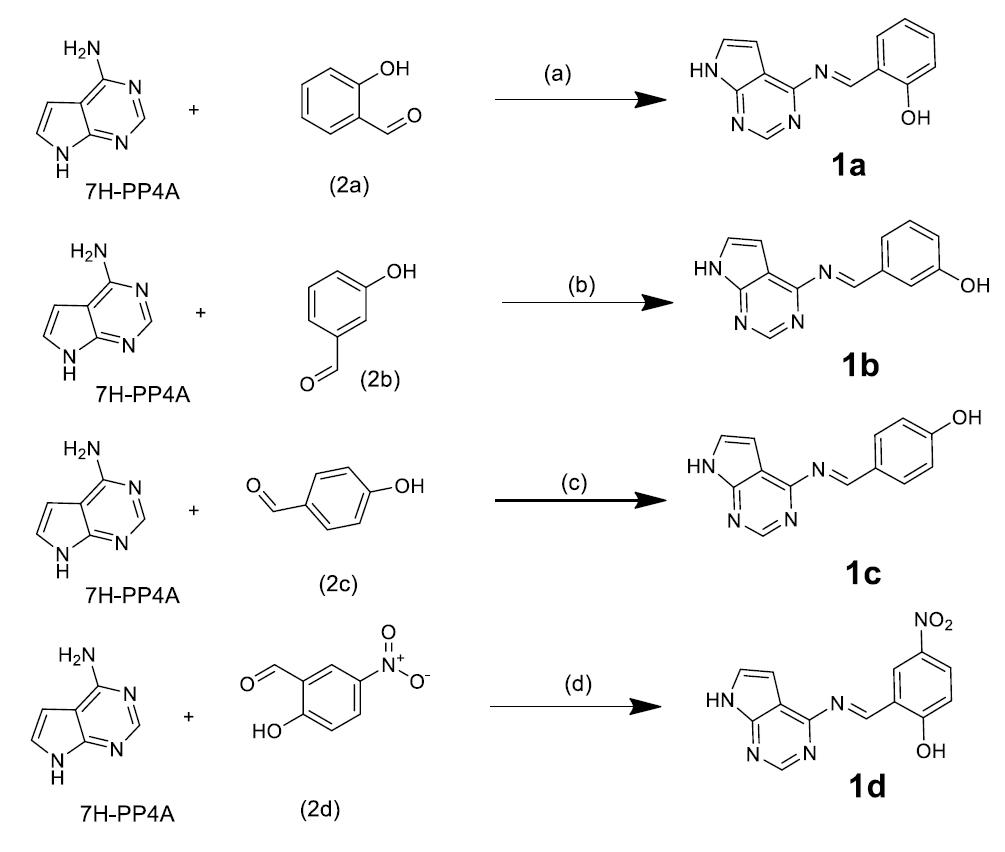

The synthesis of 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP) has been reported in various journals\(^{36}\). Figure 1 illustrates the synthesis of the target molecule by reacting 7H- pyrrolo[2,3-d] pyrimidin-4-amine with hydroxybenzaldehyde analogue in ethanol solvent in the presence of a catalytic amount of hydrochloric acid. This reaction yields the desired compounds (1a-1d). With the corresponding yield ratios shown in Table 1, \(^{1}\)H NMR spectra show a proton signal in the region 11-13 ppm, which corresponds to the presence of the –NH– group of the prolyl ring. Additionally, protons in the region 8.047-10.341 ppm are attributed to the aldehyde –CH= group. The successful substitution of the amino group by Schiff base was confirmed by the presence of an aromatic proton in the 7-8 ppm range, indicating the formation of the desired compound.

The synthesized compounds 1a-1d also show a characteristic IR absorption band. The azomethine (HC=NN-) group displays a prominent band in the range of 1654-1673 cm\(^{-1}\), confirming the formation of the imine band\(^{37}\). Two additional bands, at 1582-1588 and 1475-1509 cm\(^{-1}\), are observed in the IR spectra of 1a-1d, corresponding to the \(>\)C=C stretch of an aromatic ring

The compounds 1a-1d, dissolved in DMF, were analysed by UV spectroscopy at room temperature. The UV spectra of 1a-1d exhibit an aromatic band between 233–298 nm, originating from the \(\pi \rightarrow \pi^{*}\) transition in the benzene ring. Furthermore, the \(n \rightarrow \pi^{*}\) transition in the non- bonding electrons on the nitrogen of the azomethine group causes an extension of the absorption band in the range of 327–370 nm.

Microwave irradiation was utilized as an alternative approach for conducting the reaction. This catalyst-free technique offers several advantages, including significantly reduced reaction time, lower solvent consumption, and milder operating temperatures compared to conventional methods. Figure 1 illustrates the reactions performed under microwave conditions, while the corresponding yields are detailed in Table 1. The purity of the synthesized compounds was confirmed using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Notably, the microwave-assisted method achieved higher yields (71.54–85.02%), demonstrating its superiority over conventional techniques in terms of both efficiency and productivity.

In Microwave irradiation: (a), (b), (c), and (d) DMF at 60–65\(^\circ\)C.

All compounds were recrystallized in ethanol.

Experimental data indicate that DMF is the optimal solvent. The reaction was performed using a 1.0 equivalent ratio of benzaldehyde derivatives.

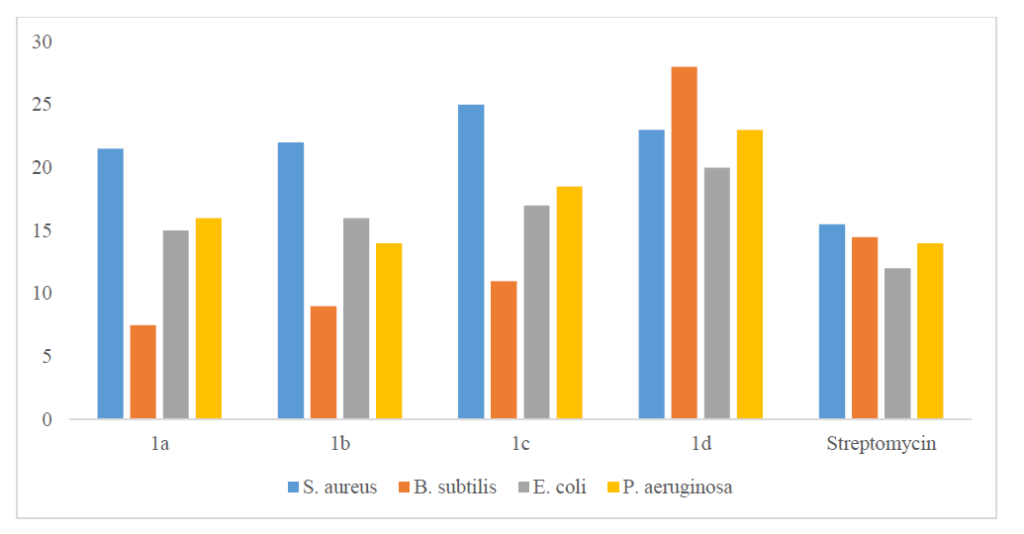

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized compounds was assessed by in vitro testing against various bacterial and fungal strains. In the antibacterial screening, all compounds had MIC values between 7.5 and 28 mm against S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. All synthesized compounds had greater inhibitory values (20.0–25.5 mm) against Staphylococcus aureus than streptomycin. Antibacterial activities of 1a-1d compounds are given in Table 4 and antibacterial activities of 1a-1d compounds and standard drug chart is given in Figure 2.

| Antibacterial Activity (zone of inhibition) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa |

| 1a | 21.5 | 7.5 | 15.0 | 16.0 |

| 1b | 22.0 | 9.0 | 16.0 | 14.0 |

| 1c | 25.0 | 11.0 | 17.0 | 18.5 |

| 1d | 23.0 | 28.0 | 20.0 | 23.0 |

| Streptomycin | 15.5 | 14.5 | 12 | 14 |

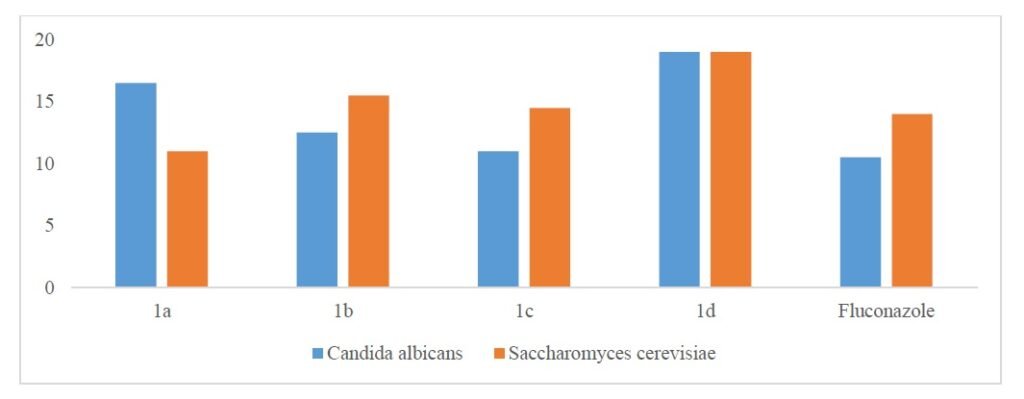

The synthesized compounds were around 2.5 times as effective as the reference drug fluconazole (10.5–14.0 mm) in antifungal experiments against the two fungi (C. albicans MCC1439 and S. cerevisiae MCC1033). Antifungal activities of 1a-1d compounds are presented in Table 5. For antifungal activities of 1a-1d compounds and standard drug, see Figure 3.

| Compound | Candida albicans | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | 16.5 | 11.0 |

| 1b | 12.5 | 15.5 |

| 1c | 11.0 | 14.5 |

| 1d | 19.0 | 19.0 |

| Fluconazole | 10.5 | 14.0 |

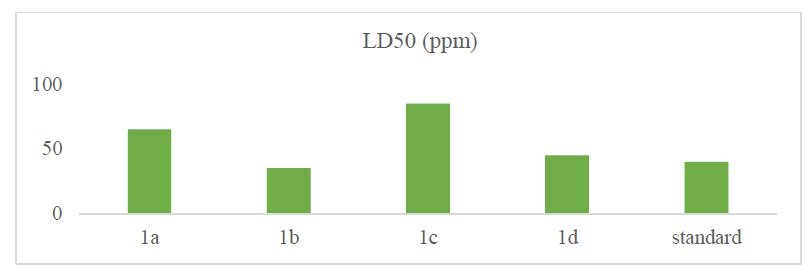

With LD\(_{50}\) values between 3.50 and 8.50 \(\times 10^{-4}\) M/mL\(^{25-28}\), all of the synthesized compounds showed cytotoxic action against Artemia salina. Brine shrimp bioassay of 1a-1d compounds are presented in Table 6 and for brine shrimp bioassay of 1a-1d compounds and standard drug, see Figure 4.

| Compound | LD\(_{50}\) (M) |

|---|---|

| 1a | \(>6.50 \times 10^{-4}\) |

| 1b | \(>3.50 \times 10^{-4}\) |

| 1c | \(>8.50 \times 10^{-4}\) |

| 1d | \(>4.50 \times 10^{-4}\) |

| Vincristine sulphate | \(>5.28 \times 10^{-4}\) |

Molecular docking studies were conducted to evaluate the binding affinities and interaction profiles of synthesized compounds against target proteins from Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, PDB: 2W9H), Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, PDB: 1RX2), and fungal (Candida albicans, PDB: 5TZ1) pathogens. The results provide insights into the potential antimicrobial and antifungal activities of these compounds compared to standard drugs, streptomycin and fluconazole.

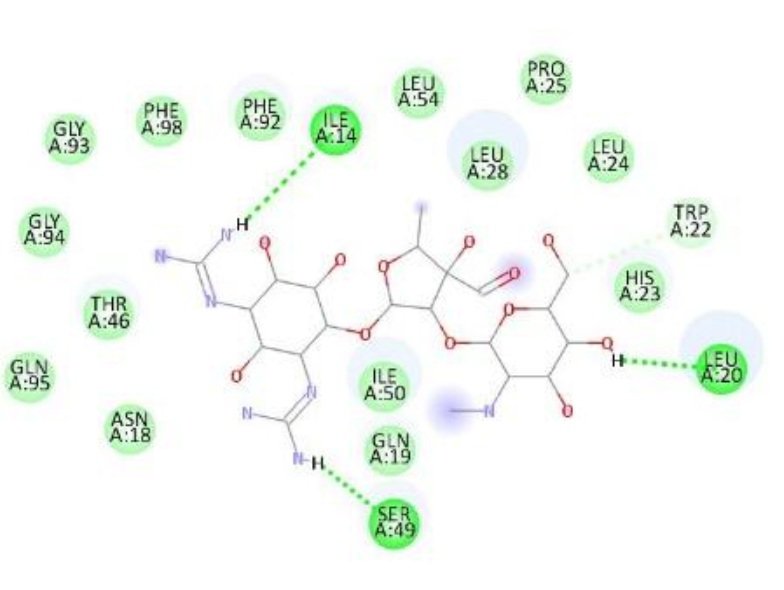

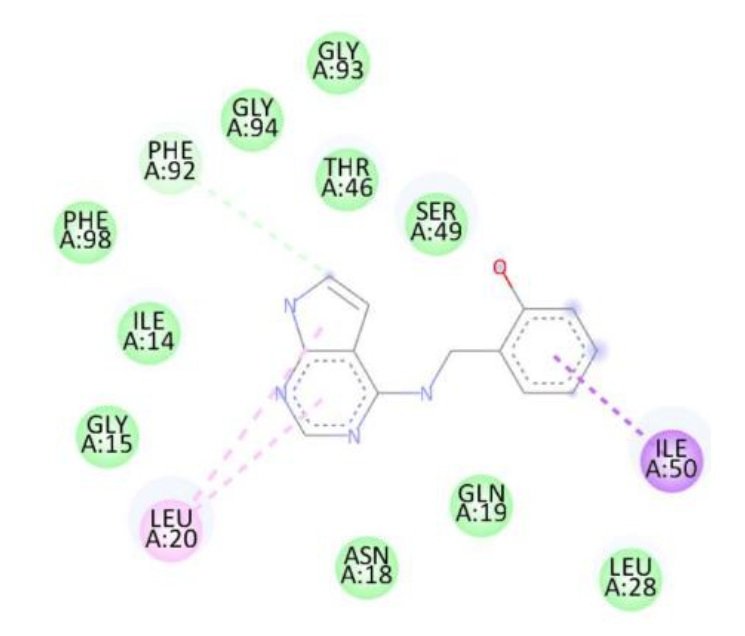

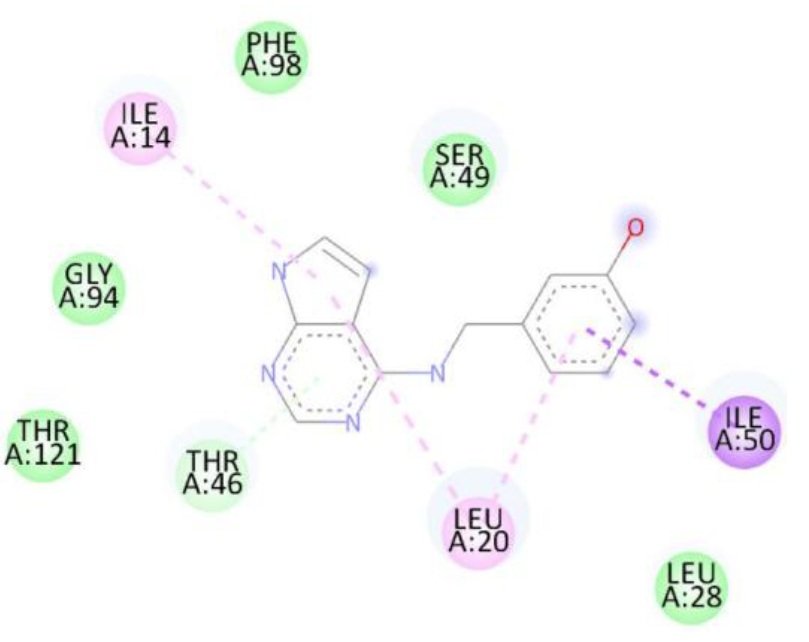

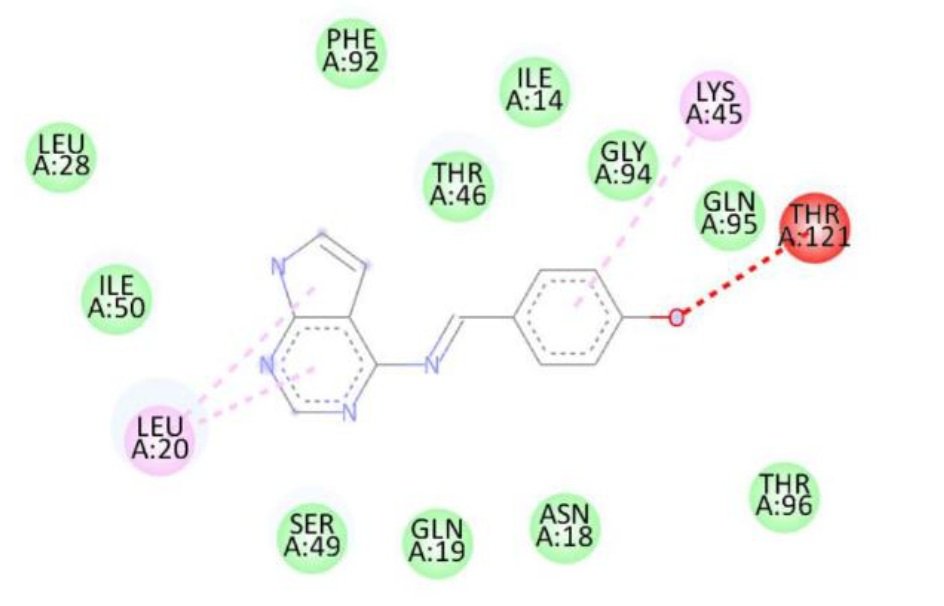

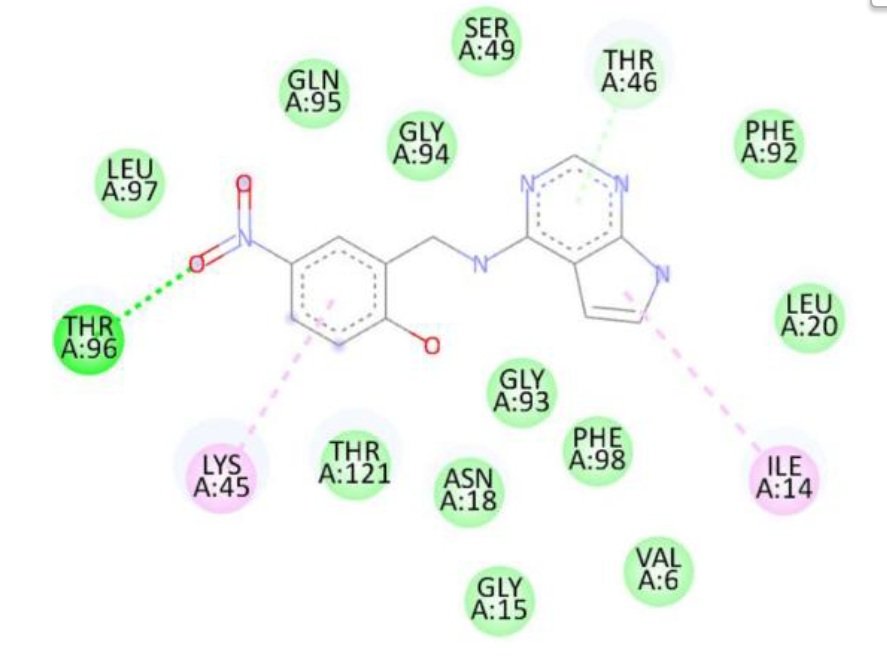

The docking results for the target protein of Staphylococcus aureus revealed that all synthesized ligands exhibited significant binding affinities, with binding energies ranging from \(-8.4\) to \(-9.0\) kcal/mol (Table 7). The reference compound, streptomycin, displayed a binding energy of \(-8.4\) kcal/mol, forming hydrogen bonds with Ile14, Ser49, and Leu20. Among the tested ligands, compound 1d demonstrated the highest binding affinity (\(-9.0\) kcal/mol), forming a hydrogen bond with Thr96 and engaging in additional hydrophobic interactions with Lys45, Ile14, and Thr46. Compounds 1a, 1b, and 1c exhibited binding energies of \(-8.5\), \(-8.5\), and \(-8.4\) kcal/mol, respectively, interacting with key hydrophobic residues such as Leu20, Ile50, and Lys45. The calculated root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.675 Å indicates a reliable binding pose alignment, suggesting high docking accuracy and minimal deviation from the predicted binding conformation.

| Comp | H-bond | Other Interactions | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | Ile14, Ser49, Leu20 | — | -8.4 |

| 1a | — | Phe92, Ile50, Leu20 | -8.5 |

| 1b | — | Thr46, Ile14, Leu20, Ile50 | -8.5 |

| 1c | — | Thr121, Lys45, Leu20 | -8.4 |

| 1d | Thr96 | Lys45, Ile14, Thr46 | -9.0 |

The superior binding energies of all compounds compared to streptomycin highlight their potential as promising candidates for combating S. aureus infections. Notably, compound 1d’s enhanced affinity, driven by both hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, suggests a stronger interaction with the active site, which may translate to improved antibacterial activity. Figure 5 shows treptomycin 2D interactions with 2W9H, Figure 6 shows 1a 2D interactions with 2W9H, Figure 7 shows 1b 2D interactions with 2W9H, Figure 8 shows 1c 2D interactions with 2W9H and Figure 9 1d 2D interactions with 2W9H.

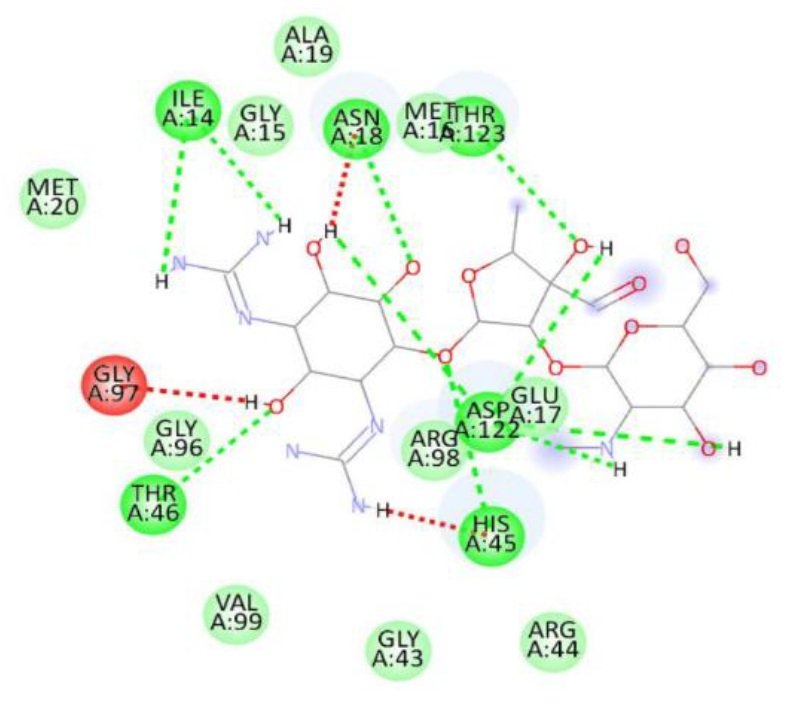

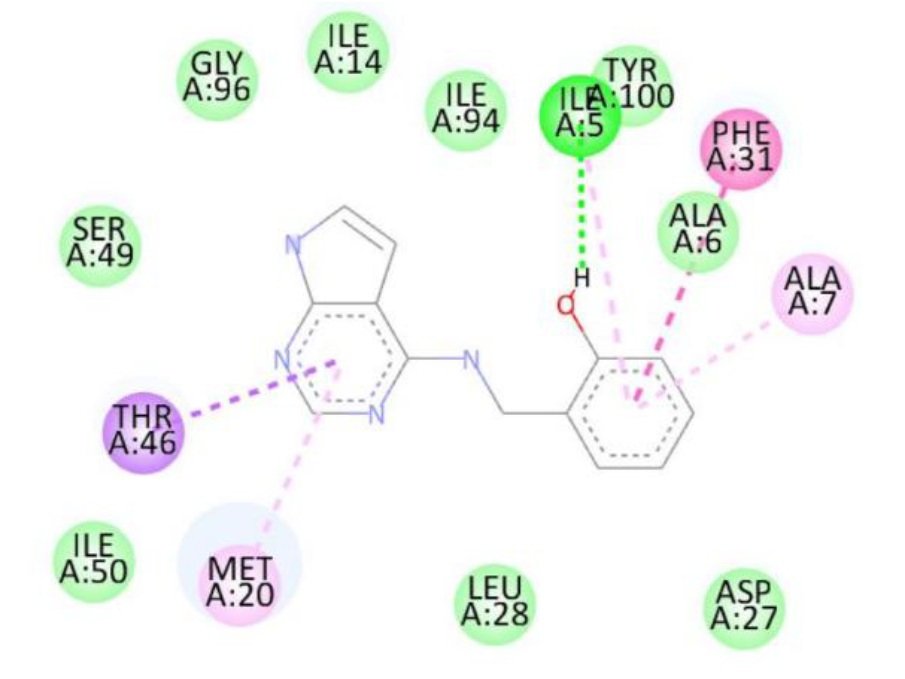

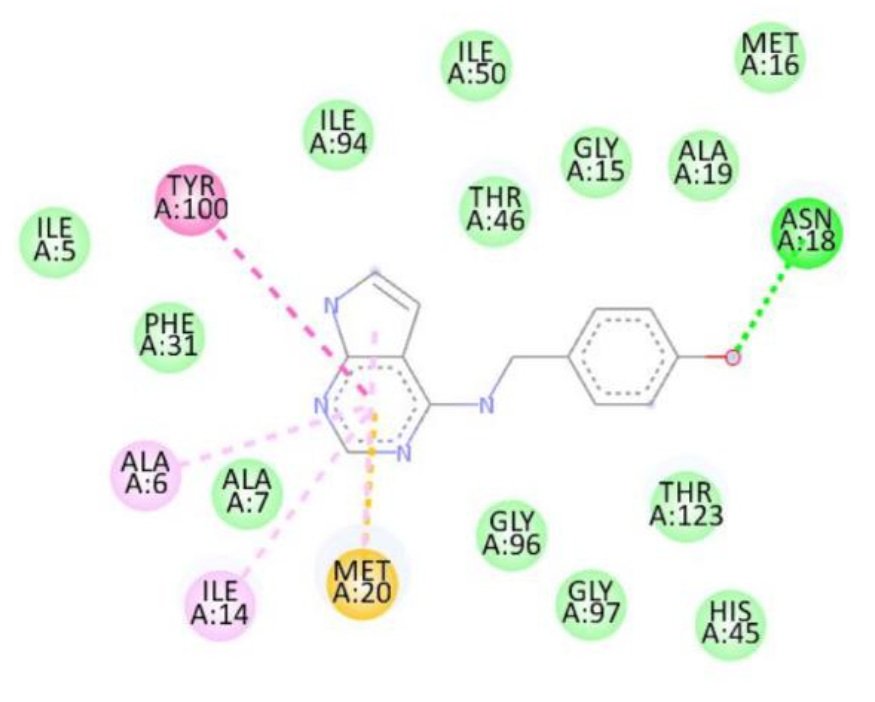

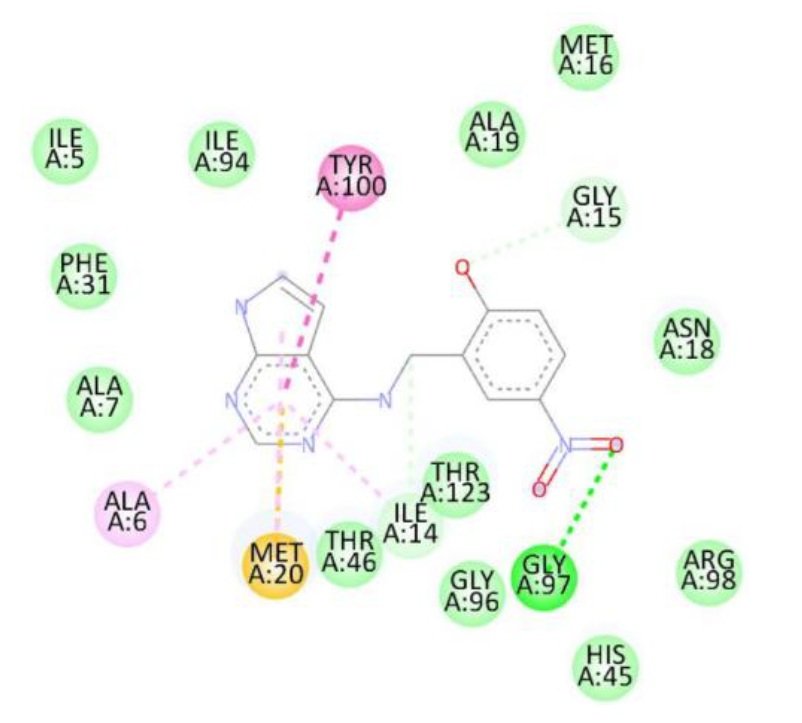

For the Escherichia coli target protein, docking studies indicated that all compounds exhibited appreciable binding affinities, with binding energies ranging from \(-7.1\) to \(-8.3\) kcal/mol (Table 8). Streptomycin, the reference compound, showed a binding energy of \(-7.1\) kcal/mol, forming multiple hydrogen bonds with Ile14, Asn18, Thr123, Asp122, His45, and Thr46, alongside non-covalent interactions with His45 and Gly97. Among the synthesized compounds, compound 1d exhibited the highest binding affinity (\(-8.3\) kcal/mol), forming a hydrogen bond with Gly97 and interacting with key residues including Met20, Ile14, Ala6, Tyr100, and Gly15. Compounds 1a, 1b, and 1c displayed binding energies of \(-7.7\), \(-7.7\), and \(-7.4\) kcal/mol, respectively, engaging in both hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with residues such as Met20, Ala6, Ile14, and Tyr100. The RMSD value of 0.785 Å confirms a reliable binding pose alignment, indicating good docking accuracy.

The improved binding energies of the compounds compared to streptomycin suggest their potential as effective agents against E. coli. The high affinity of compound 1d, driven by specific interactions with the active site, underscores its promise for further development as an antibacterial agent. Figure 10 shows streptomycin 2D interactions with 1RX2, Figure 11 shows 1a 2D interactions with 1RX2 Figure 12 shows 1b 2D interactions with 1RX2, Figure 13 shows 1c 2D interactions with 1RX2 and Figure 14 shows 1d 2D interactions with 1RX2.

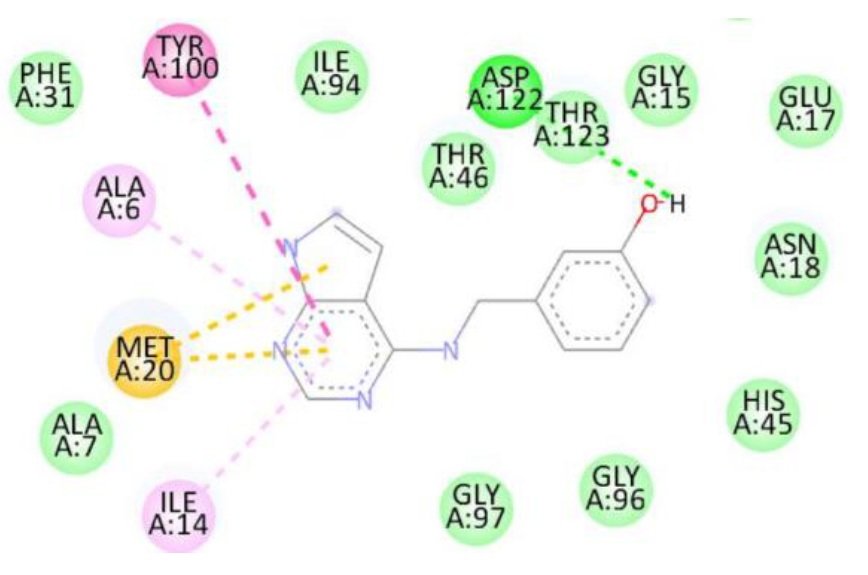

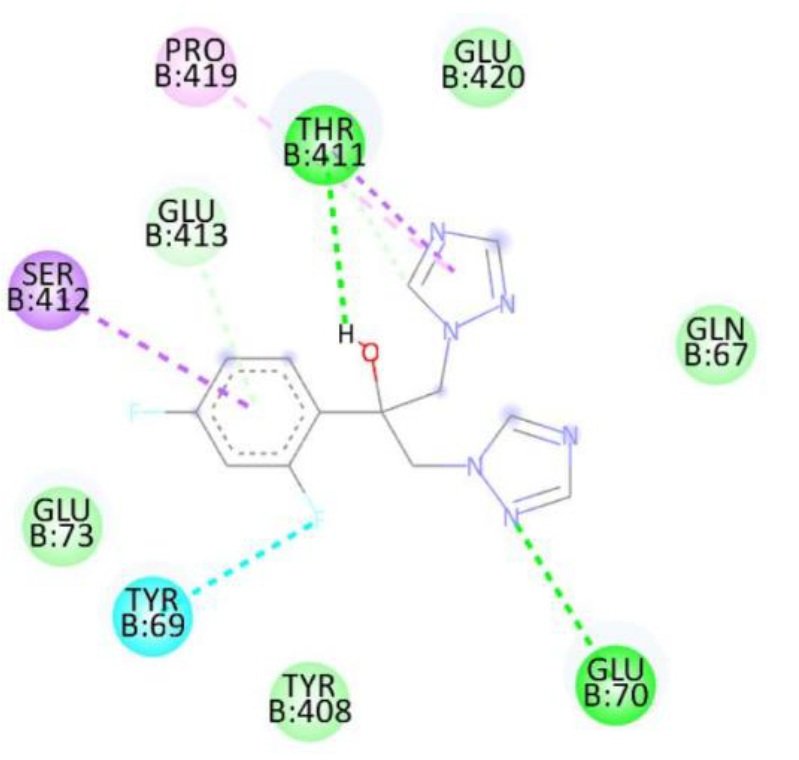

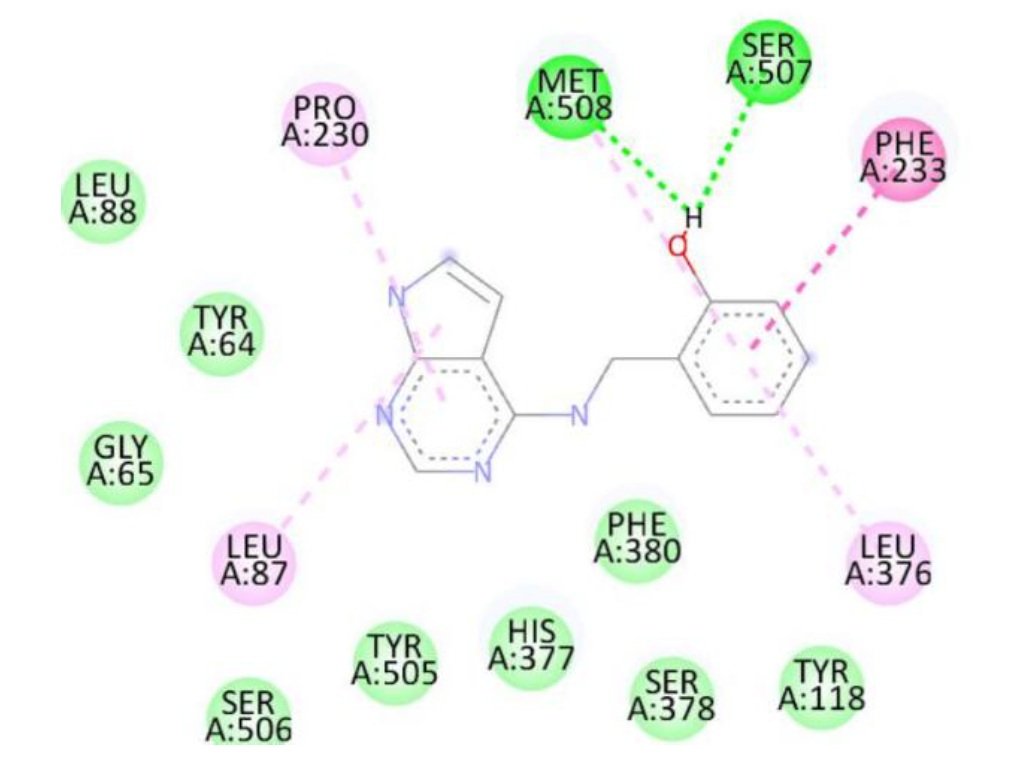

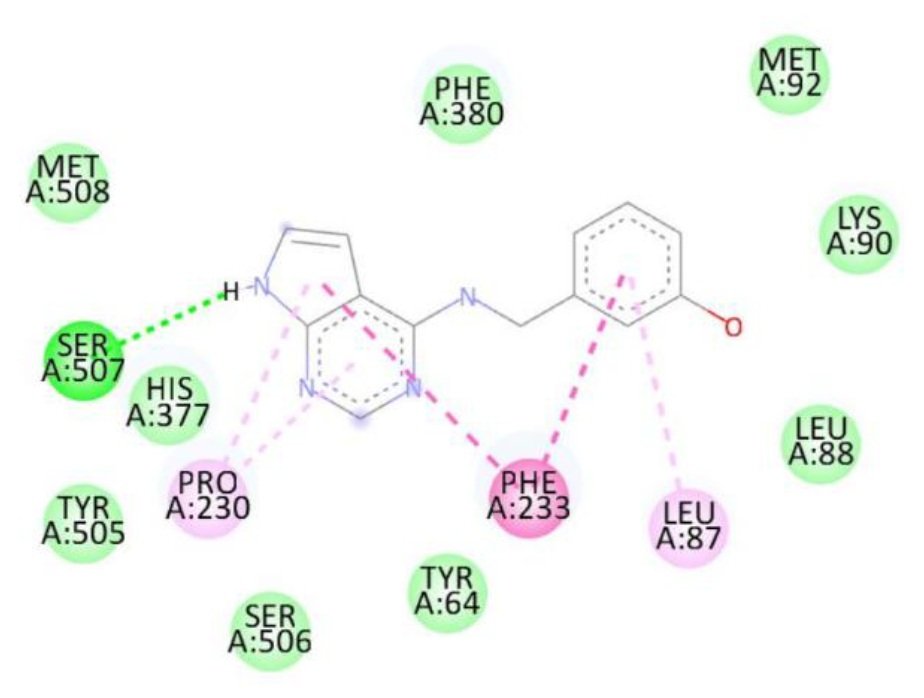

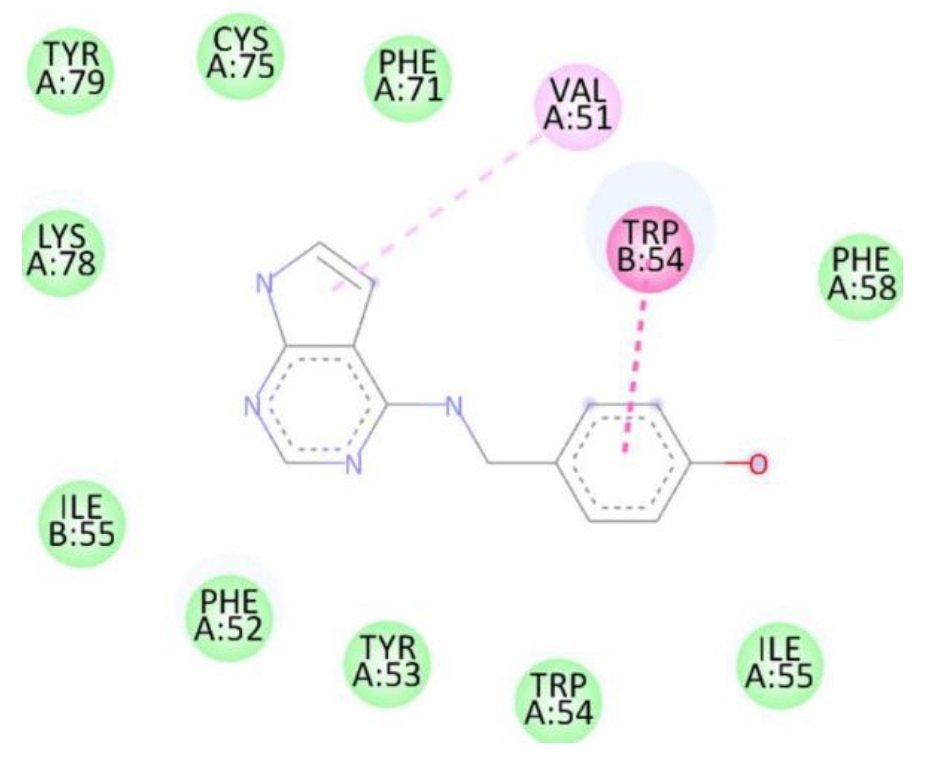

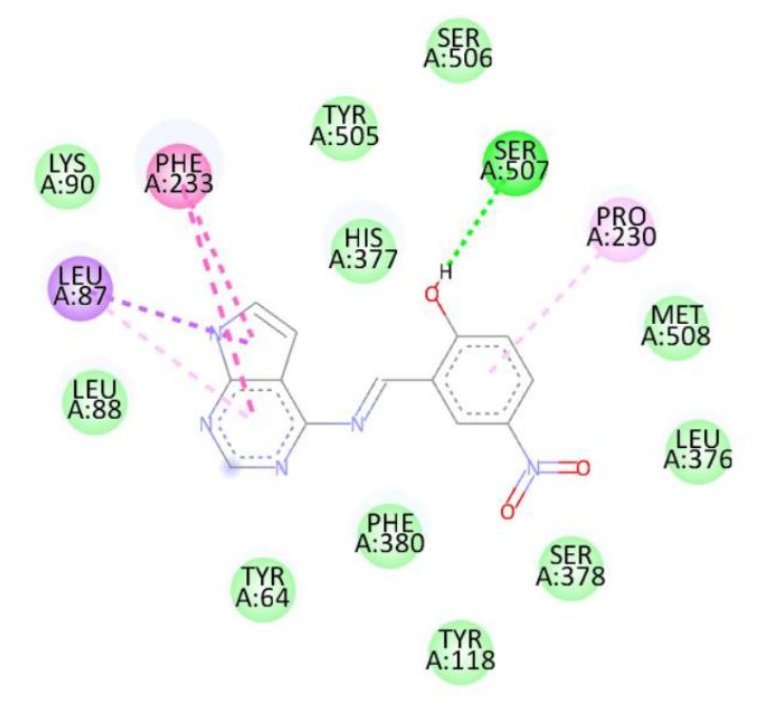

Docking studies against the Candida albicans target protein demonstrated that all designed compounds exhibited favorable binding affinities compared to the standard antifungal drug fluconazole, which showed a binding energy of \(-7.3\) kcal/mol (Table 9). Fluconazole formed hydrogen bonds with Thr411 and Glu70, along with additional interactions with Pro419, Ser412, Tyr69, and Thr411. Among the tested compounds, compound 1b exhibited the highest binding affinity (\(-8.3\) kcal/mol), forming a hydrogen bond with Ser507 and engaging in hydrophobic interactions with Pro230, Phe233, and Leu87. Compound 1d also displayed a high binding energy of \(-8.2\) kcal/mol, interacting with Ser507, Pro230, Phe233, and Leu7. Compound 1a formed hydrogen bonds with Met508 and Ser507, along with interactions with Pro230, Leu87, Leu376, and Phe233, resulting in a binding energy of \(-7.7\) kcal/mol. Although compound 1c did not form hydrogen bonds, it interacted with Val51 and Trp54, yielding a binding energy of \(-7.6\) kcal/mol. The RMSD value of 0.655 Å confirms a reliable binding pose alignment, indicating high docking accuracy.

The enhanced binding energies of compounds 1b and 1d, compared to fluconazole, suggest stronger and potentially more effective binding to the C. albicans target protein. These findings indicate that these compounds may offer improved antifungal activity, warranting further investigation. Figure 15 shows Fluconazole 2D interactions with 5TZ1, Figure 16 shows 1a 2D interactions with 5TZ1, Figure 17 shows 1b 2D interactions with 5TZ1, Figure 18 shows 1c 2D interactions with 5TZ1 and Figure 19 shows 1d 2D interactions with 5TZ1.

| Compounds | H-bond | Other Interactions | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Thr411, Glu70 | Pro419, Ser412, Tyr69, Thr411 | -7.3 |

| 1a | Met508, Ser507 | Pro230, Leu87, Leu376, Phe233 | -7.7 |

| 1b | Ser507 | Pro230, Phe233, Leu87 | -8.3 |

| 1c | — | Val51, Trp54 | -7.6 |

| 1d | Ser507 | Pro230, Phe233, Leu7 | -8.2 |

The docking studies collectively demonstrate that the synthesized compounds outperform the reference compounds (streptomycin for bacteria and fluconazole for fungi) across all tested pathogens. For S. aureus and E. coli, compound 1d consistently exhibited the highest binding affinities (\(-9.0\) and \(-8.3\) kcal/mol, respectively), driven by a combination of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with key active site residues. These interactions likely stabilize the ligand-protein complex, enhancing binding strength and potentially improving antibacterial efficacy. Similarly, for C. albicans, compounds 1b and 1d showed superior binding affinities (-8.3 and -8.2 kcal/mol, respectively) compared to fluconazole, suggesting their potential as potent antifungal agents.

The low RMSD values (0.655–0.785 Å) across all docking studies confirm the reliability and accuracy of the predicted binding poses, reinforcing the robustness of the computational approach. The consistent outperformance of the synthesized compounds compared to standard drugs highlights their potential for further development as novel antimicrobial and antifungal agents. The diverse interaction profiles, involving both hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, suggest that these ligands can effectively target a broad spectrum of pathogens, addressing the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Future studies should focus on validating these findings through in vitro and in vivo experiments to confirm the predicted antimicrobial and antifungal activities. Additionally, structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses could guide the optimization of these ligands to further enhance their binding affinities and pharmacological properties.

In this study, we successfully synthesized a series of novel substituted benzaldehyde derivatives of 4-Amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (4A7HPP), designated as compounds 1a–1d, using microwave irradiation. This method proved to be a safe, cost-effective, and efficient approach for imine formation, eliminating the need for a base and yielding superior results compared to conventional synthesis techniques. Comprehensive characterization through spectral studies and elemental analysis (C, H, N, O) confirmed the structural integrity of the synthesized compounds.

The biological evaluation demonstrated that these compounds exhibit potent antibacterial and antifungal activities against sensitive cell lines, including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans. Molecular docking studies further revealed that compounds 1d and 1b possess superior binding affinities compared to the reference drugs streptomycin and fluconazole, with reliable RMSD values indicating robust docking accuracy. These findings highlight the potential of these ligands as promising candidates for the development of novel antimicrobial and antifungal therapies.

The combination of efficient synthesis via microwave irradiation and the promising bioactivity of these compounds underscores their therapeutic potential. However, further experimental validation, including in vitro and in vivo studies, is essential to confirm these computational insights and facilitate their translation into clinical applications. This work lays a strong foundation for future research into optimizing these derivatives for enhanced efficacy and addressing the pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Sayed Mohamed, M. O. S. A. A. D., El-Domany, R. A., & Abd El-Hameed, R. H. (2009). Sinteza derivata pirola kao antimikrobnih tvari. Acta Pharmaceutica, 59(2), 145-158.

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Soerjomataram, I., & Jemal, A. (2024). Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 74(3), 229-263.

Hilmy, K. M. H., Khalifa, M. M., Hawata, M. A. A., Keshk, R. M. A., & El-Torgman, A. A. (2010). Synthesis of new pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives as antibacterial and antifungal agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 45(11), 5243-5250.

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. (2019). Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 7-34.

Boyle, P., & Levin, B. (2008). World Cancer Report 2008 (pp. 510-pp). Lyon: IARC Press.

Blume-Jensen, P., & Hunter, T. (2001). Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature, 411(6835), 355-365.

Pathania, S., & Rawal, R. K. (2018). Pyrrolopyrimidines: An update on recent advancements in their medicinal attributes. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 157, 503-526.

van der Westhuyzen, A. E., Frolova, L. V., Kornienko, A., & van Otterlo, W. A. (2018). The Rigidins: Isolation, bioactivity, and total synthesis—novel pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidine analogues using multicomponent reactions. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology, 79, 191-220.

Ishwar Bhat, K., Kumar, A., Nisar, M., & Kumar, P. (2014). Synthesis, pharmacological and biological screening of some novel pyrimidine derivatives. Medicinal Chemistry Research, 23(7), 3458-3467.

Patil, S. B. (2018). Biological and medicinal significance of pyrimidines: A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 9, 44–52.

Krawczyk, S. H., Nassiri, M. R., Kucera, L. S., Kern, E. R., Ptak, R. G., Wotring, L. L., … & Townsend, L. B. (1995). Synthesis and antiproliferative and antiviral activity of 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoroarabinofuranosyl analogs of the nucleoside antibiotics toyocamycin and sangivamycin. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 38(20), 4106-4114.

Ghorab, M. M., Heiba, H. I., Khalil, A. I., Abou El Ella, D. A., & Noaman, E. (2007). Computer-based ligand design and synthesis of some new sulfonamides bearing pyrrole or pyrrolopyrimidine moieties having potential antitumor and radioprotective activities. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon and the Related Elements, 183(1), 90-104.

Supuran, C. T., Scozzafava, A., Jurca, B. C., & Ilies, M. A. (1998). Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors-Part 49: Synthesis of substituted ureido and thioureido derivatives of aromatic/heterocyclic sulfonamides with increased affinities for isozyme I. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 33(2), 83-93.

Faidallah, H. M., Rostom, S. A., Badr, M. H., Ismail, A. E., & Almohammadi, A. M. (2015). Synthesis of Some 1, 4, 6‐Trisubstituted‐2‐oxo‐1, 2‐dihydropyridine‐3‐carbonitriles and Their Biological Evaluation as Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Agents. Archiv Der Pharmazie, 348(11), 824-834.

Varaprasad, C. (2016). In-class peer feedback: Effectiveness and student engagement. The Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(2), 155-172.

Varaprasad, C. V., Ramasamy, K. S., Girardet, J. L., Gunic, E., Lai, V., Zhong, W., … & Hong, Z. (2007). Synthesis of pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidine nucleoside derivatives as potential anti-HCV agents. Bioorganic Chemistry, 35(1), 25-34.

Ivanov, M. A., Ivanov, A. V., Krasnitskaya, I. A., Smirnova, O. A., Karpenko, I. L., Belanov, E. F., … & Alexandrova, L. A. (2008). New furano-and pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidine nucleosides and their 5’-O-triphosphates: Synthesis and biological properties. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry, 34(5), 593-601.

Mohamed, M. S., Rashad, A. E., Adbel-Monem, M., & Fatahalla, S. S. (2007). New anti-inflammatory agents. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C, 62(1-2), 27-31.

Alqasoumi, S. I., Ghorab, M. M., Ismail, Z. H., Abdel-Gawad, S. M., El-Gaby, M. S., & Aly, H. M. (2009). Novel antitumor acetamide, pyrrole, pyrrolopyrimidine, thiocyanate, hydrazone, pyrazole, isothiocyanate and thiophene derivatives containing a biologically active pyrazole moiety. Arzneimittelforschung, 59(12), 666-671.

Jung, M. H., Kim, H., Choi, W. K., El-Gamal, M. I., Park, J. H., Yoo, K. H., … & Oh, C. H. (2009). Synthesis of pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives and their antiproliferative activity against melanoma cell line. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 19(23), 6538-6543.

Asukai, Y., Valladares, A., Camps, C., Wood, E., Taipale, K., Arellano, J., … & Dilla, T. (2010). Cost-effectiveness analysis of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in the second-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in Spain: results for the non-squamous histology population. BMC Cancer, 10(1), 26.

McHardy, T., Caldwell, J. J., Cheung, K. M., Hunter, L. J., Taylor, K., Rowlands, M., … & Collins, I. (2010). Discovery of 4-amino-1-(7 H-pyrrolo [2, 3-d] pyrimidin-4-yl) piperidine-4-carboxamides as selective, orally active inhibitors of protein kinase B (Akt). Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 53(5), 2239-2249.

Sayed Mohamed, M. O. S. A. A. D., El-Domany, R. A., & Abd El-Hameed, R. H. (2009). Sinteza derivata pirola kao antimikrobnih tvari. Acta Pharmaceutica, 59(2), 145-158.

Smith, F., Cousins, B., Bozic, J., & Flora, W. (1985). The acid dissolution of sulfide mineral samples under pressure in a microwave oven. Analytica Chimica Acta, 177, 243-245.

Wan, J. K. S., Wolf, K., & Heyding, R. D. (1984). Some Chemical Aspects of the Microwave Assisted Catalytic Hydro-Cracking Processes** This research is supported by the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority and the Department of Energy, Mines, Resources, Canada. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, 19, 561-568.

Kumar, P., & Gupta, K. C. (1996). Microwave assisted synthesis of S-trityl and S-acylmercaptoalkanols, nucleosides and their deprotection. Chemistry Letters, 25(8), 635-636.

Nadkarni, R. A. (1984). Applications of microwave oven sample dissolution in analysis. Analytical Chemistry, 56(12), 2233-2237.

Bacci, M. (1982). Spectroscopic and structural properties of metallo-proteins. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento (1978-1999), 5(12), 1-45.

Gedye, R. N., Smith, F. E., & Westaway, K. C. (1988). The rapid synthesis of organic compounds in microwave ovens. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 66(1), 17-26.

Patil, Y., Shingare, R., Choudhari, A., Sarkar, D., & Madje, B. (2019). Microwave‐Assisted Synthesis and Antituberculosis Screening of Some 4‐((3‐(Trifluoromethyl)‐5, 6‐dihydro‐[1, 2, 4] triazolo [4, 3‐a] pyrazin‐7 (8 H)‐l) methyl) benzenamine Hybrids. Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry, 56(2), 434-442.

Fennie, M. W., & Roth, J. M. (2016). Comparing amide-forming reactions using green chemistry metrics in an undergraduate organic laboratory. Journal of Chemical Education, 93(10), 1788-1793.

Tiwari, S., & Talreja, S. (2022). Green chemistry and microwave irradiation technique: a review. Green Chemistry, 11, 15.

Ardila‐Fierro, K. J., & Hernández, J. G. (2021). Sustainability assessment of mechanochemistry by using the twelve principles of green chemistry. ChemSusChem, 14(10), 2145-2162.

Poondra, R. R., & Turner, N. J. (2005). Microwave-assisted sequential amide bond formation and intramolecular amidation: a rapid entry to functionalized oxindoles. Organic Letters, 7(5), 863-866.

Seanego, T. D., Chavalala, H. E., Henning, H. H., de Koning, C. B., Hoppe, H. C., Ojo, K. K., & Rousseau, A. L. (2022). 7H‐Pyrrolo [2, 3‐d] pyrimidine‐4‐amines as Potential Inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum Calcium‐Dependent Protein Kinases. ChemMedChem, 17(22), e202200421.

Moosavi‐Zare, A. R., Goudarziafshar, H., & Saki, K. (2018). Synthesis of pyranopyrazoles using nano‐Fe‐[phenylsalicylaldiminemethylpyranopyrazole] Cl2 as a new Schiff base complex and catalyst. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 32(1), e3968.

Magaldi, S., Mata-Essayag, S., De Capriles, C. H., Pérez, C., Colella, M. T., Olaizola, C., & Ontiveros, Y. (2004). Well diffusion for antifungal susceptibility testing. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 8(1), 39-45.

Kumar, A., & Mishra, A. K. (2015). Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some new diphenylamine derivatives. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences, 7(1), 81-85.

Nath, A. R., & Reddy, M. S. (2012). Design, Synthesis, Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Novel 2‐[(E)‐2‐aryl‐1‐ethenyl]‐3‐(2‐sulfanyl‐1H‐benzo [d] imidazole‐5‐yl)‐3, 4‐dihydro‐4‐quinolinones. Journal of Chemistry, 9(3), 1481-1489.

Abbott, W. S. (1925). A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology 18(2), 265-267.