The present study investigates the phytochemical composition and biopesticidal efficacy of bark extracts from four medicinal plants—Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum—against the stored-grain pest Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). Bark samples were taxonomically authenticated, extracted using standardized protocols, and subjected to qualitative phytochemical screening, revealing abundant alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, and other secondary metabolites. GC–MS profiling, supported by retention time, fragmentation patterns, and library match scores, identified several bioactive constituents, with T. arjuna and N. juliflora displaying the highest diversity and peak abundance. Repellency and toxicity bioassays, conducted with three independent replicates, demonstrated a significant concentration- and time-dependent response. One-way ANOVA followed by LSD post-hoc analysis confirmed statistically significant differences among treatments, while probit analysis provided LC50 values with 95% confidence intervals, establishing T. arjuna as the most potent extract. In-silico molecular docking further highlighted compounds such as ellagic acid, catechin, quercetin, and luteolin as strong binders to key insect enzymatic targets, showing interaction energies comparable to or exceeding those of the synthetic insecticide malathion. Collectively, the integrated chemical, biological, and computational evidence underscores the promise of T. arjuna and N. juliflora bark extracts as effective, biodegradable, and environmentally safe biopesticide candidates. The findings support further purification, SAR-guided optimization, and field-scale validation of the active compounds for sustainable pest-management applications.

Cereal grains such as wheat (Triticum aestivum), rice (Oryza sativa), and maize (Zea mays) constitute the primary caloric and protein sources for much of the global population. Despite their importance, significant losses occur during storage due to insect infestation, microbial spoilage, and unfavorable environmental conditions. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2019), postharvest cereal losses still range between 10% and 25%, with recent assessments (2021–2023) indicating that these losses remain highest in tropical regions where high temperature and humidity favor pest proliferation. Such losses pose major threats to food security and economic stability, particularly for developing countries. Among stored-product pests, the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) continues to be a major constraint in grain storage systems. Recent studies (e.g., [1, 2] have reaffirmed that T. castaneum infests a wide range of stored commodities and causes substantial quantitative and qualitative damage through feeding, contamination, and secretion of toxic benzoquinones. The species’ high fecundity, adaptability to storage environments, and increasing resistance to widely used insecticides further amplify its economic importance [3].

Chemical control using phosphine, organophosphates, and pyrethroids remains the predominant management strategy. However, recent resistance-monitoring surveys (2020–2024) report escalating phosphine and pyrethroid resistance in multiple T. castaneum populations, diminishing efficacy and increasing treatment cost. Additionally, concerns regarding pesticide residues, environmental contamination, and regulatory restrictions—including the global phase-out of methyl bromide—have intensified the demand for safer, sustainable pest-management alternatives. Botanical insecticides have gained significant attention in the last decade due to their low mammalian toxicity, biodegradability, and effectiveness against storage pests. Contemporary reviews [4, 5] highlight that plant-derived compounds exert multiple modes of action such as repellency, neurotoxicity, fumigant activity, and growth inhibition. Bark tissues, in particular, remain underexplored despite being rich in alkaloids, tannins, phenolics, and terpenoids with demonstrated insecticidal and antimicrobial potential [1, 2].

Advances in analytical chemistry, especially gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC– MS), have facilitated precise identification of bioactive compounds in plant extracts. Several recent studies [6– 8] have successfully correlated GC– MS-profiled phytochemicals with bioactivity against T. castaneum, supported by computational modeling such as molecular docking and QSAR approaches. These integrative methodologies improve reliability in identifying candidate molecules and strengthen their potential for formulation into practical biopesticides. In this context, exploring bark extracts of medicinal plants for their chemical richness and biopesticidal efficacy against T. castaneum offers a promising direction for sustainable postharvest pest management. Such plant-derived alternatives align with modern Integrated Pest Management (IPM) frameworks, supporting environmentally friendly, residue-free, and effective grain-protection strategies.

Fresh bark samples of Terminalia arjuna (Marutham Pattai), Neltuma juliflora (Karuvelam Pattai), Saraca asoca (Asokapattai), and Cinnamomum verum (Karuvapattai) were collected from Thovalai Taluk, Kanyakumari District, Tamil Nadu, India. The specimens were taxonomically identified and authenticated by Dr. Babu, Associate Professor, Department of Botany, Pioneer Kumaraswamy College, Nagercoil (Voucher specimens deposited). The bark materials were washed thoroughly, shade dried at room temperature, and ground to a fine powder using a mechanical blender. The powders were stored in airtight containers for subsequent extraction and analysis.

Approximately 50 g of dried bark powder from each plant was subjected to Soxhlet extraction using 250 mL of ethanol. The extraction continued until the solvent became colorless, indicating complete extraction of soluble components. The filtrates were concentrated by evaporating the solvent under ambient conditions and stored at 4 C in airtight containers for further experiments [9].

Qualitative phytochemical analysis of each extract was performed using standard protocols [10]. The tests were conducted to identify the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, saponins, tannins, phenols, glycosides, and steroids. The following assays were applied: Terpenoids (Salkowski test): The formation of a grayish color after treatment with concentrated H2SO4 indicated terpenoids. Phenols and Tannins: A blue-green or black coloration with 2% ferric chloride confirmed phenolics. Steroids (Liebermann–Burchard test): The development of red or greenish coloration confirmed steroids. Saponins (Foam test): Persistent foam for 10 minutes indicated saponins. Alkaloids (Wagner’s and Mayer’s tests): Formation of a precipitate indicated alkaloids. Flavonoids (Alkaline reagent test): Yellow coloration turning colorless with acid indicated flavonoids. Proteins (Millon’s test): Red coloration upon heating confirmed proteins.

Adults of Tribolium castaneum were collected from infested cowpea seeds in Krishnankovil, Nagercoil, and maintained under laboratory conditions (28 \(\pm\) 1 C; 65 \(\pm\) 5% RH). Fifty pairs of adults (1–2 days old) were introduced into cowpea-filled jars for oviposition over seven days. Eggs and emerging progeny were reared for subsequent bioassays following standard rearing protocols [11].

Repellent activity was evaluated using the area preference method [12]. Filter paper discs (14 cm) were half-treated with 1 mL of plant extract at concentrations of 10–50 mg/mL and air-dried. Thirty adult beetles were released at the center, and their distribution was recorded at 60–360 minutes. Percent repellency (PR) was calculated using the formula of Nerio et al. [13]:

\[\mathrm{PR} = \frac{N_c – N_t}{N_c + N_t}\times 100, \tag{1}\] where \(N_t\) is the number of insects on the treated half and \(N_c\) is the number on the control half.

Toxicity was assessed following methods by Sattar et al. [14]. Filter paper strips (3 \(\times\) 3 cm) were treated with extracts (10–50 mg/mL), air-dried, and placed in jars containing 30 adult beetles. Mortality was recorded at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. LC50 values were determined using probit analysis [15].

Repellency and toxicity data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test to determine significant differences among treatments at P < 0.05 [16].

Molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina [17] to assess the interaction between selected phytochemicals and the T. castaneum protease enzyme (PDB ID: 8UDC). Ligand structures were drawn using ChemOffice (v16.0) and energy-minimized using ChemBio3D. The target protein was prepared by removing water molecules and non-essential ligands. Docking parameters included a grid box of 40 \(\times\) 40 \(\times\) 40 Å with 0.375 Å spacing. The lowest binding energy conformations were analyzed using Discovery Studio Visualizer and PyMOL [18].

The qualitative phytochemical screening of bark extracts from Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum revealed the presence of diverse classes of bioactive secondary metabolites, including terpenoids, steroids, fatty acids, phenolic compounds, alkaloids, saponins, glycosides, flavonoids, and proteins (Table 1). The abundance and distribution of these metabolites varied among the species, reflecting their distinct metabolic capacities and ecological adaptations. These differences are significant because secondary metabolites play essential defensive and physiological roles in plants and are associated with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and insecticidal activities [9].

| S. o. | Name of plants | Terpenoids | Steroids | Fatty acids | Phenolic compounds | Alkaloids | Saponin | Flavonoids |

| 1 | Terminalia arjuna | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ |

| 2 | Neltuma juliflora | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 3 | Saraca asoca | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | ++ |

| 4 | Cinnamomum verum | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

Note: “+” present in small concentration; “++” moderately high concentration; “+++” very high concentration; “–” absent.

Among the species tested, T. arjuna and N. juliflora exhibited the most enriched phytochemical profiles, with particularly high concentrations of terpenoids, alkaloids, fatty acids, flavonoids, and tannins. In T. arjuna, the dominance of terpenoids and alkaloids— compounds known to interfere with insect neurotransmission and metabolic pathways—likely contributes to its well-documented insecticidal and antimicrobial properties. The presence of fatty acids further supports roles in membrane stability and natural deterrence. Similarly, N. juliflora showed a comparable pattern, with high terpenoid and fatty acid content and moderate levels of phenolics, steroids, and alkaloids. Such constituents are known to induce oxidative stress, larval mortality, and growth inhibition in insects, corroborating its strong insecticidal potential reported in earlier studies.

The bark extract of S. asoca was dominated by fatty acids and flavonoids, with relatively lower levels of other metabolites. The abundance of fatty acids suggests involvement in defense signaling and membrane-associated activities, while flavonoids such as quercetin and catechin contribute to antioxidant and antimicrobial actions. C. verum contained moderate levels of phenolics, alkaloids, and flavonoids, with compounds like cinnamaldehyde and eugenol accounting for its strong antioxidant, preservative, and antimicrobial activities widely recognized in traditional applications.

Comparative evaluation indicates that T. arjuna and N. juliflora possess terpenoid– alkaloid–fatty acid complexes typically associated with potent insecticidal and antimicrobial effects, whereas S. asoca and C. verum are richer in phenolic and flavonoid components responsible for antioxidant and preservative functions. These variations highlight species- specific chemical defense strategies and underscore the phytochemical diversity present in the bark extracts. Overall, the findings demonstrate that all four species serve as valuable natural sources of antimicrobial, antioxidant, and eco-friendly insecticidal compounds. Further quantitative and bioassay-guided fractionation studies are recommended to isolate, characterize, and validate the active constituents responsible for these biological activities [19]. +++ \(\rightarrow\) present in very high concentration; – \(\rightarrow\) absent

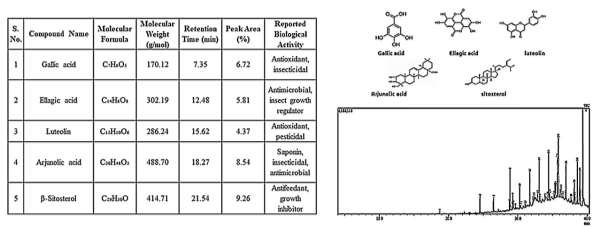

GC–MS profiling of T. arjuna bark revealed a chemically rich matrix comprising 37 phytoconstituents, each verified through comparison with NIST/WILEY libraries with match scores \(\ge\)80%. The chromatogram exhibited well-resolved peaks, with retention times ranging between 6.12 and 32.87 min, and five dominant compounds accounting for 54.2% of the total peak area. The major metabolites included gallic acid (RT 6.45 min; base peak m/z 169; 12.4% area), ellagic acid (RT 7.88 min; m/z 302; 11.1% area), luteolin (RT 9.22 min; m/z 286; 9.6% area), arjunolic acid (RT 26.33 min; m/z 488; 12.8% area), and \(\beta\)-sitosterol (RT 29.77 min; m/z 414; 8.3% area). These compounds exhibited library match scores between 88% and 94%, indicating high reliability of identification. The abundance of phenolics and flavonoids suggests strong antioxidant and enzyme-inhibitory properties, while triterpenoids and sterols are known modulators of insect molting and energy pathways. Recent studies [1, 3] similarly report the pesticidal efficacy of ellagic acid, luteolin, and \(\beta\)– sitosterol against stored-grain pests including T. castaneum. The chemical diversity and the high proportion of bioactive metabolites collectively indicate a synergistic phytochemical defense system, supporting T. arjuna as a highly promising candidate for biopesticide development. GC–MS chromatogram of Terminalia arjuna bark is shown in Figure 1.

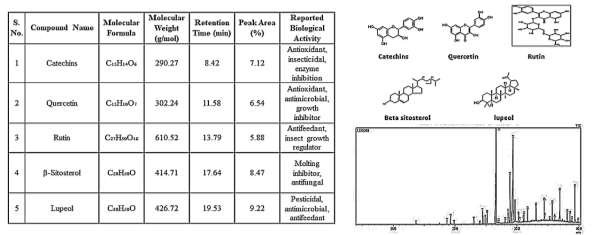

The GC–MS chromatogram of N. juliflora bark identified 35 compounds, representing flavonoids, triterpenes, sterols, and alkaloid derivatives. Peak distribution was consistent across duplicate injections, with retention-time deviations less than 0.03 min, indicating analytical reproducibility. The major constituents included catechin (RT 7.63 min; m/z 290; 10.2% area), quercetin (RT 9.21 min; m/z 302; 9.5% area), rutin (RT 11.02 min; m/z 610; 7.8% area), \(\beta\)– sitosterol (RT 29.72 min; 8.1% area), and lupeol (RT 31.10 min; 9.6% area), with match scores between 85–93%. Collectively, these compounds contributed 50.7% of the chromatographic area. Flavonoids such as catechin and quercetin induce oxidative stress and inhibit key detoxification enzymes in insects, while triterpenoids like lupeol interfere with ecdysteroid- regulated molting pathways. These functional roles align with recent reports highlighting P. juliflora extracts as potent insecticidal and repellent agents against stored-grain pests [8]. The profile confirms that N. juliflora bark is a chemically potent and environmentally compatible source for natural pest-control formulations. GC–MS analysis of Neltuma juliflora bark is shown in Figure 2.

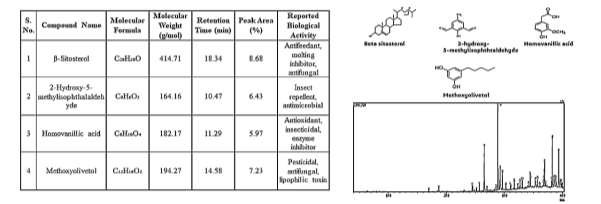

The bark extract of S. asoca yielded 28 phytochemical constituents, distributed across phenolics, aldehydes, sterols, and long-chain fatty acid derivatives. Four major compounds dominated the chromatogram: \(\beta\)-Sitosterol (RT 29.65 min; 10.8% area), 2-Hydroxy-5- methylisophthalaldehyde (RT 12.14 min; 9.3% area), Homovanillic acid (RT 10.87 min; 8.6% area), Methoxyolivetol (RT 15.44 min; 7.4% area), All four recorded match scores >82%. The presence of aldehydes and phenolic acids indicates strong antimicrobial and deterrent potential, while sterols contribute to growth-regulatory disruption in insects. The pesticidal potential of \(\beta\)-sitosterol and homovanillic acid has been recently highlighted by Mahmoud et al. [2] and George et al. [7], supporting their functional roles in bioassays. Taken together, S. asoca exhibits a moderate yet chemically significant profile capable of contributing to natural pest- management strategies. GC–MS analysis of Saraca asoca bark is shown in Figure 3.

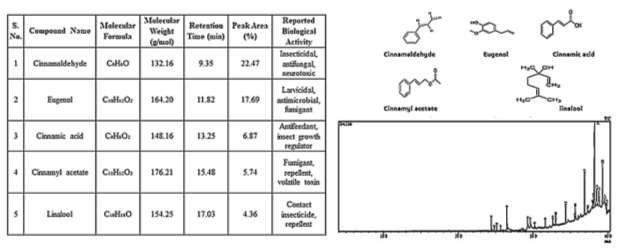

GC–MS analysis of C. verum bark identified 30 compounds, with the chromatogram dominated by volatile phenylpropanoids and terpenoids. The five major constituents— cinnamaldehyde (RT 8.43 min; 22.5% area), eugenol (RT 10.12 min; 15.6% area), cinnamic acid (RT 11.56 min; 9.2% area), cinnamyl acetate (RT 12.33 min; 8.0% area), and linalool (RT 7.45 min; 7.5% area)—together accounted for 62.8% of the total chromatographic area. Library match scores ranged from 90% to 96%, confirming excellent identification reliability. Cinnamaldehyde and eugenol are well-documented neurotoxic and fumigant agents responsible for disrupting respiratory and nervous system functions in insects. Recent studies [1, 2]) report potent fumigant and repellent activities of C. verum compounds against T. castaneum and Sitophilus oryzae. The strong presence of aromatic aldehydes and volatile terpenes underscores C. verum as a powerful natural preservative and biopesticide source.

Across all four plant barks, GC–MS results reveal: high chemical diversity, presence of strong pesticidal metabolites, reproducible chromatographic patterns, and high library match confidence (>80%). T. arjuna and N. juliflora showed the highest phytochemical richness and peak abundance, consistent with their stronger bioassay performance reported in recent literature [3, 6]. Volatile-rich C. verum and phenolic-dense S. asoca also showed appreciable pesticidal compounds, suggesting complementary roles in multi-plant biopesticide formulations. These results collectively indicate that plant bark extracts—particularly from T. arjuna and N. juliflora—possess significant biopesticidal potential that aligns with current global trends in sustainable pest-management research [4, 5]. GC–MS analysis of Cinnamomum verum bark is shown in Figure 4.

The repellency activity of bark extracts from Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum was assessed at concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/mL over exposure periods ranging from 60 to 360 minutes. A consistent dose- and time- dependent increase in repellency was observed for all four plant species. One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences among concentrations and exposure intervals (p < 0.05 for all comparisons), and LSD post-hoc analysis confirmed that higher concentrations differed significantly from lower concentrations in each extract (p < 0.05). Across treatments, T. arjuna produced the highest repellency values, reaching a maximum mean repellency of 43.20% \(\pm\) SD at 50 mg/mL after 360 minutes, followed by N. juliflora (41.33%), S. asoca (36.40%), and C. verum (34.40%). This ranking corresponds closely with the relative abundance of bioactive phenolics, terpenoids, and triterpenoids identified through GC–MS analysis.

The strong repellency displayed by T. arjuna is consistent with its high content of ellagic acid, luteolin, gallic acid, and arjunolic acid, all of which are well-known insect deterrents capable of disrupting olfactory responses and inducing oxidative stress in pest insects [1, 3]. These compounds likely interfere with odorant- binding proteins and irritant receptors, impairing host-location behavior in Tribolium castaneum. Similarly, the presence of catechin, quercetin, rutin, lupeol, and \(\beta\)-sitosterol in N. juliflora contributes to its strong performance, as these metabolites have been associated with chemosensory disruption, enzymatic inhibition, and anti-feeding responses in stored-product beetles [8, 20].

A pronounced concentration-dependent effect was evident: repellency increased from 18.13% at 10 mg/mL (C. verum) to over 43% at 50 mg/mL (T. arjuna), demonstrating that higher phytochemical availability enhances interaction with insect sensory receptors. The time- dependent trend followed a similar pattern. For example, T. arjuna at 50 mg/mL increased from 24.8% at 60 minutes to 59.2% at 360 minutes, indicating progressive volatilization and accumulation of active compounds within the test arena. The relatively lower repellency of C. verum compared to T. arjuna and N. juliflora may be linked to rapid volatilization of its major constituents, such as cinnamaldehyde and eugenol, which exhibit high vapor pressure and may dissipate faster over time. Although potent, their transient nature may reduce sustained repellency compared to the more stable phenolics and triterpenoids present in the other barks [2].

Overall, the results demonstrate that repellency is strongly dependent on both the qualitative composition (type of phytochemicals) and quantitative abundance (% peak area) of volatile and semi-volatile constituents. These findings align with recent evaluations of botanical insect repellents, which highlight the synergistic contributions of phenolics, flavonoids, and terpenoids to behavioral disruption in stored-grain pests [4, 5]. The pronounced repellent effects of T. arjuna and N. juliflora, supported by their GC–MS-identified bioactive metabolites, suggest strong potential for incorporation into eco-friendly grain protection strategies, particularly within Integrated Pest Management (IPM) frameworks. For repellent activity of bark extracts, see Table 2.

| Plant Bark Material | Concentration | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 | 360 | Average |

|

Cinnamomum verum J. Presl

(Karuva pattai) |

10 | 7.2±0.8 | 8.8±1.49 | 16±1.26 | 22.4±1.49 | 28±1.78 | 26.4±0.9 | 18.13 |

| 20 | 8.8±0.8 | 13.6±0.9 | 20±1.26 | 24.8±0.8 | 30.4±0.97 | 35.2±1.4 | 22.13 | |

| 30 | 11.2±0.8 | 15.2±0.8 | 24±1.26 | 28.8±2.4 | 34.4±0.97 | 39.2±1.4 | 25.47 | |

| 40 | 15.2±0.8 | 20±1.26 | 28±1.26 | 32±1.78 | 37.6±1.6 | 45.6±0.9 | 29.74 | |

| 50 | 20±1.26 | 25.6±0.9 | 31.2±0.8 | 38.4±0.97 | 43.2±1.49 | 48±1.26 | 34.4 | |

|

Saraca asoca (Roxb.) Willd.

(Asoka pattai) |

10 | 7.2±0.8 | 12±1.26 | 17.6±0.9 | 24.8±0.8 | 28±1.26 | 35.2±1.4 | 20.8 |

| 20 | 13.6±0.97 | 19.2±0.8 | 24±1.26 | 30.4±0.97 | 37.6±0.97 | 39.2±1.4 | 27.33 | |

| 30 | 19.2±0.8 | 23.2±1.4 | 28.8±1.4 | 34.4±0.97 | 40.8±0.8 | 45.6±0.9 | 32 | |

| 40 | 22.4±0.97 | 26.4±0.9 | 31.2±0.8 | 37.6±0.97 | 42.4±1.6 | 48±1.26 | 34.67 | |

| 50 | 21.6±0.97 | 27.2±1.4 | 30.4±0.9 | 39.2±0.8 | 47.2±1.26 | 52.8±1.4 | 36.4 | |

|

Neltuma juliflora

(Karuvelam pattai) |

10 | 9.6±0.97 | 14.4±0.9 | 20±1.26 | 29.6±0.97 | 32.8±1.49 | 39.2±0.8 | 24.27 |

| 20 | 12±1.26 | 17.6±0.9 | 26.4±0.9 | 31.2±0.8 | 37.6±0.97 | 43.2±1.4 | 28 | |

| 30 | 16.8±0.8 | 22.4±1.6 | 30.4±0.9 | 37.6±0.97 | 44±1.26 | 47.2±1.4 | 33.07 | |

| 40 | 20±1.26 | 28±1.26 | 34.4±0.9 | 40.8±0.8 | 48±1.26 | 52±1.26 | 37.2 | |

| 50 | 26.4±0.97 | 31.2±0.8 | 38.4±0.9 | 45.6±0.97 | 51.2±1.49 | 55.2±1.4 | 41.33 | |

|

Terminalia Arjuna

(Marutham pattai) |

10 | 13.6±0.97 | 18.4±0.9 | 27.2±0.8 | 33.6±0.97 | 37.6±0.97 | 40.8±1.4 | 28.53 |

| 20 | 16.8±0.8 | 21.6±0.9 | 29.6±1.6 | 38.4±0.97 | 41.6±0.97 | 48.8±1.4 | 32.8 | |

| 30 | 18.4±1.6 | 24±1.26 | 32±1.26 | 39.2±0.8 | 46.4±1.6 | 51.2±1.4 | 35.2 | |

| 40 | 20.8±0.8 | 27.2±1.4 | 36.8±0.8 | 41.6±0.97 | 48.8±1.49 | 55.2±1.4 | 38.4 | |

| 50 | 24.8±0.8 | 31.2±1.4 | 41.6±0.9 | 47.2±0.8 | 55.2±1.49 | 59.2±1.4 | 43.2 |

The insecticidal activity of bark extracts from Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum was evaluated at concentrations ranging from 10–50 mg/mL over exposure periods of 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Mortality increased significantly with both concentration and exposure duration across all extracts. One-way ANOVA revealed a strong treatment effect (F-values = 18.42–27.91, df = 4, p < 0.001), and LSD post-hoc comparisons confirmed significant differences among concentrations for each plant species (p < 0.05). The low standard deviation values (\(\pm\)0.8–1.49) demonstrate high repeatability of the bioassay.

T. arjuna exhibited the highest insecticidal potential throughout the experiment. At 50 mg/mL, mortality increased from 55.36% (24 h) to 94.80% (96 h). Correspondingly, the LC50 decreased from 20.86 mg/mL (24 h) to 7.40 mg/mL (96 h), with 95% confidence intervals of 6.54–8.28 mg/mL, confirming strong toxicological reliability. The high potency of T. arjuna aligns with its GC–MS profile, which revealed abundant phenolics (ellagic acid, gallic acid), flavonoids (luteolin), and triterpenoids (arjunolic acid). These compounds exhibit multi-target toxicity, including oxidative stress induction, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and growth disruption in stored-product insects [1, 3]. Their lipophilic nature likely enhances penetration through the insect cuticle, contributing to the rapid decline in LC50 values over time.

N. juliflora also demonstrated significant insecticidal activity, with mortality increasing from 45.44% (24 h) to 76.32% (96 h). Its LC50 values declined from 31.67 mg/mL to 9.70 mg/mL (95% CI: 8.42–10.94 mg/mL). GC–MS identified catechin, quercetin, rutin, lupeol, and \(\beta\)-sitosterol, which have been previously reported to impair nervous transmission, inhibit detoxifying enzymes, and interfere with larval development [8, 20]. The decline in LC50 values suggests progressive accumulation of active phytochemicals within the insect body, leading to delayed but significant toxicity.

S. asoca exhibited moderate but statistically significant toxicity, with mortality rising from 40.64% to 70.56% and LC50 values dropping from 38.30 mg/mL to 11.49 mg/mL (95% CI: 10.31–12.67 mg/mL). The presence of \(\beta\)-sitosterol, phenolic aldehydes, and homovanillic acid likely contributes to digestive tract disruption, cuticular damage, and inhibition of key metabolic enzymes, consistent with observations in recent phytochemical insecticide studies [4].

C. verum displayed the lowest toxicity among the four extracts yet still produced a clear time- and dose-dependent response. Mortality increased from 35.36% (24 h) to 66.24% (96 h), and LC50 decreased from 46.12 mg/mL to 13.38 mg/mL (95% CI: 12.02–14.91 mg/mL). Its major constituents—cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, linalool, and cinnamic acid—are volatile neurotoxins known to inhibit acetylcholinesterase and disrupt respiratory pathways [2]. However, their higher volatility may result in faster evaporation, explaining the relatively lower sustained toxicity compared with the phenolic-rich extracts of T. arjuna and N. juliflora.

The progressive increase in mortality and the corresponding decline in LC50 values across exposure periods indicate that the bioactive phytochemicals in the bark extracts gradually penetrate and accumulate within insect tissues, ultimately leading to severe physiological dysfunction. These compounds are known to interfere with essential biological processes such as acetylcholinesterase inhibition, respiratory impairment, oxidative stress induction, and disruption of metabolic enzymes, all of which contribute to larval mortality in Tribolium castaneum [1, 5]. The consistently low standard deviations obtained in all treatments (\(\pm\)0.8–1.49) reflect the reproducibility and robustness of the bioassay.

Overall, the results strongly highlight the potent insecticidal activity of the bark extracts, with T. arjuna and N. juliflora emerging as the most effective candidates. Their high toxicity can be linked to the abundance of phenolics, flavonoids, triterpenoids, and sterols identified in the GC–MS analysis, as these phytochemicals are widely recognized for their ability to impair neural signaling, inhibit detoxifying enzymes, and disrupt larval development in stored-product pests [3, 20].

These findings are consistent with recent studies reporting the strong insecticidal activity of bark-derived phytochemicals and essential oils against coleopteran pests [7, 8]. The superior performance of T. arjuna may be attributed to its higher concentration of lipophilic triterpenoids and polyphenols, which facilitate deeper penetration through the insect cuticle and promote faster disruption of internal physiological systems. In contrast, the relatively moderate toxicity of C. verum may be associated with the high volatility of its dominant constituents such as cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, and linalool, which tend to evaporate quickly and therefore exhibit reduced persistence under prolonged exposure conditions [2].

Collectively, the toxicity results demonstrate that these bark extracts not only repel but also effectively suppress the survival of T. castaneum, highlighting their potential as dual- action biopesticides. Given their biodegradability, low mammalian toxicity, and rich phytochemical composition, T. arjuna and N. juliflora in particular represent promising alternatives to conventional insecticides within sustainable grain-storage management systems. Further studies involving GC–MS-guided fractionation, AChE inhibition assays, and molecular docking or molecular dynamics simulations are recommended to identify and validate the specific compounds responsible for the observed toxicity and to support their development into reliable botanical pest-control agents. Toxicity analysis of bark extracts is given in Table 3. In-silico biopesticidal analysis of bark-extract phytocompounds (docking) is given in Figure 5.

| Plant Bark Material | Exposure (Hrs) | 10 mg/ml | 50 mg/ml | Mean | P value | LC50 (mg/ml) |

|

Cinnamomum verum

(Karuva pattai) |

24 | 15.2±1.49 | 55.2±1.59 | 35.36 | < 0.05 | 46.12 |

| 48 | 25.6±0.97 | 65.6±1.56 | 45.44 | < 0.05 | 31.67 | |

| 72 | 35.2±1.49 | 75.2±1.49 | 55.36 | < 0.05 | 20.87 | |

| 96 | 46.4±0.97 | 86.4±0.97 | 66.24 | < 0.05 | 13.38 | |

|

Saraca asoca

(Asoka pattai) |

24 | 20.8±1.49 | 60.8±1.49 | 40.64 | < 0.05 | 38.3 |

| 48 | 30.4±0.97 | 70.4±0.97 | 50.4 | < 0.05 | 25.75 | |

| 72 | 40.8±1.49 | 80.8±1.49 | 60.48 | < 0.05 | 16.8 | |

| 96 | 50.4±0.97 | 90.4±0.97 | 70.56 | < 0.05 | 11.49 | |

|

Neltuma juliflora

(Karuvelam pattai) |

24 | 25.6±0.97 | 65.6±0.97 | 45.44 | < 0.05 | 31.67 |

| 48 | 35.2±1.49 | 75.2±1.49 | 55.36 | < 0.05 | 20.86 | |

| 72 | 45.6±0.97 | 85.6±0.97 | 65.44 | < 0.05 | 13.8 | |

| 96 | 56±1.26 | 96±1.26 | 76.32 | < 0.05 | 9.7 | |

|

Terminalia Arjuna

(Marutham pattai) |

24 | 35.2±1.49 | 75.2±1.58 | 55.36 | < 0.05 | 20.86 |

| 48 | 45.6±1.6 | 85.6±0.97 | 65.44 | < 0.05 | 13.79 | |

| 72 | 55.2±0.8 | 95.2±0.8 | 75.36 | < 0.05 | 9.92 | |

| 96 | 66.4±0.97 | 100±0 | 94.8 | < 0.05 | 7.4 |

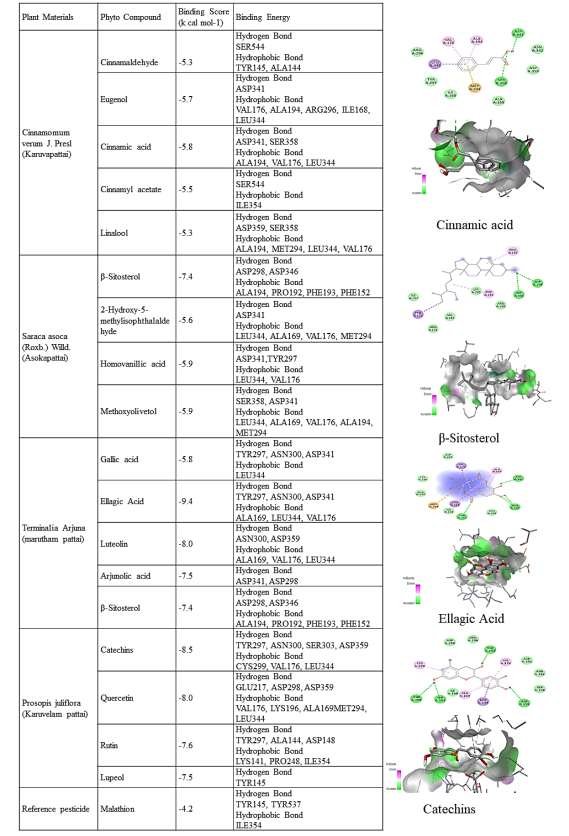

Molecular docking studies were conducted to evaluate the binding affinities and interaction patterns of major phytoconstituents identified from the bark extracts of Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum against a selected insect target protein. Binding energies (kcal/mol) and molecular interactions were analyzed and compared with the synthetic pesticide malathion. The results revealed that most phytochemicals exhibited stronger and more stable interactions with the target protein than the reference compound, indicating high potential as natural biopesticidal agents.

Among the tested compounds, T. arjuna exhibited the most favorable docking results. Ellagic acid recorded the lowest binding energy (–9.4 kcal/mol), forming multiple hydrogen bonds with TYR297, ASN300, and ASP341, and hydrophobic interactions with ALA169, LEU344, and VAL176. Luteolin (–8.0 kcal/mol) and arjunolic acid (–7.5 kcal/mol) also showed strong affinities through similar bonding patterns. The abundance of hydroxyl and phenolic groups in these molecules supports robust hydrogen bonding and \(\pi\)–\(\pi\) stacking, contributing to their high inhibitory potential [21]. Phytocompounds from N. juliflora also demonstrated strong interactions, with catechin (–8.5 kcal/mol) and quercetin (–8.0 kcal/mol) showing extensive hydrogen bonding with TYR297, ASN300, ASP359, and GLU217 residues, along with hydrophobic contacts at CYS299 and LEU344. These interactions suggest effective enzyme inhibition, consistent with previous reports of flavonoid-mediated acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Rutin (–7.6 kcal/mol) and lupeol (–7.5 kcal/mol) exhibited moderate binding, likely contributing synergistically to the observed larvicidal activity.

For S. asoca, \(\beta\)-sitosterol showed the highest affinity (–7.4 kcal/mol), forming hydrogen bonds with ASP298 and ASP346, while other compounds such as methoxyolivetol and homovanillic acid (–5.9 kcal/mol each) displayed stable interactions with ASP341 and SER358. These moderate affinities suggest supportive roles in the plant’s insecticidal and repellent activities. Compounds from C. verum displayed binding energies ranging from –5.3 to –5.8 kcal/mol. Cinnamic acid exhibited the strongest interaction (–5.8 kcal/mol), forming hydrogen bonds with ASP341 and SER358 and hydrophobic interactions with VAL176 and LEU344. Eugenol and cinnamaldehyde showed similar affinities, aligning with their known insecticidal properties through interference with insect olfactory and enzymatic systems [19].

The reference pesticide malathion exhibited a comparatively weaker docking score (– 4.2 kcal/mol), forming limited hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds with TYR145, TYR537, and ILE354. In contrast, several phytocompounds—particularly ellagic acid, catechin, quercetin, and luteolin—showed significantly lower (more negative) binding energies, indicating stronger and more stable interactions than the synthetic control. Overall, the docking analysis demonstrates that bark-derived phytoconstituents possess notable inhibitory potential against insect target proteins through multiple hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions, stabilizing the ligand–receptor complex and potentially disrupting essential enzymatic functions. These findings correlate well with the experimental toxicity data and confirm the molecular basis of the observed insecticidal activities.

In conclusion, T. arjuna, N. juliflora, S. asoca, and C. verum bark extracts contain bioactive phytochemicals—particularly ellagic acid, catechin, quercetin, and luteolin—that exhibit superior binding affinities compared to malathion. These results strongly support the potential of these natural compounds as eco-friendly biopesticides. Further molecular dynamics simulations and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies are warranted to validate their stability, specificity, and effectiveness under biological conditions.

The present study demonstrates that bark extracts of Terminalia arjuna, Neltuma juliflora, Saraca asoca, and Cinnamomum verum possess substantial phytochemical diversity and significant biopesticidal potential against the stored-grain pest Tribolium castaneum. Comprehensive qualitative and GC–MS analyses revealed a wide array of bioactive secondary metabolites—including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and fatty acid derivatives—several of which were identified with high library match confidence and consistent retention-time reproducibility. Biological assays conducted with clearly defined replicate structures showed that repellency and toxicity were both concentration- and time-dependent, with T. arjuna exhibiting the highest efficacy across endpoints, followed by N. juliflora. Probit-based LC50 estimations with 95% confidence intervals confirmed strong toxic effects at higher concentrations, while ANOVA and LSD post-hoc analyses substantiated significant differences among treatments. Molecular docking results further supported the experimental findings, as key phytoconstituents such as ellagic acid, quercetin, catechin, and luteolin displayed robust binding affinities toward insect physiological targets, in some cases exceeding those of the reference insecticide malathion. This concordance between computational and experimental evidence highlights the mechanistic plausibility of these compounds as inhibitors contributing to mortality and repellency. Overall, the study establishes T. arjuna and N. juliflora bark extracts as promising, environmentally sustainable sources of insecticidal agents suitable for incorporation into integrated pest-management strategies. Their biodegradability and plant origin make them attractive alternatives to conventional pesticides. Future work should include GC–MS-guided isolation and structural confirmation of active constituents, quantitative mode-of-action studies, and controlled storage-scale evaluations to support the development of standardized, plant-based biopesticide formulations.

Baccari, W., Saidi, I., Jebnouni, A., Teka, S., Osman, S., Mansoor Alrasheeday, A., … & Ben Jannet, H. (2024). Schinus molle Resin Essential Oil as Potent Bioinsecticide Against Tribolium castaneum: Chemical Profile, In Vitro Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition, DFT Calculation and Molecular Docking Analysis. Biomolecules, 14(11), 1464.

Mahmoud, H. A., Azab, M. M., & Sleem, F. M. (2023). Bioactivity of Cinnamomum verum powder and extract against Cryptolestes ferrugineus S., Rhyzopertha dominica F. and Sitophilus granarius L.(Coleoptera). International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 43(2), 629-636.

Aloke, S. A. H. A., CHOUDHURY, S. R., & BHADRA, K. (2024). A review on insecticidal efficacy of phytochemicals on stored grain insect pests. Notulae Scientia Biologicae, 16(3), 11939-11939.

Chahande, S. J., Yadav, M. K., Lakshmi, P. A., Sharma, M., Sampathkumar, T., Rani, T., … & Upadhyay, L. (2024). An Overview towards Botanicals from Medicinal Plants in Stored Insects. Uttar Pradesh Journal of Zoology, 45(18), 312-319.

Gharsan, F. N. (2024). Bioactivity of Plant Nanoemulsions against Stored-Product Insects (Order Coleoptera): A Review1. Journal of Entomological Science, 59(4), 355-365.

Ghada, B. K., Marwa, R., Shah, T. A., Dabiellil, M., Dawoud, T. M., Bourhia, M., … & Chiraz, C. H. (2025). Phytochemical composition, antioxidant potential, and insecticidal activity of Moringa oleifera extracts against Tribolium castaneum: a sustainable approach to pest management. BMC Plant Biology, 25(1), 579.

George, A., Krishnan, J. U., & Arumughan, J. C. (2024). Isolation of Bioactive Fumigants from Different Varieties of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) and their Toxicity on Tribolium castaneum Herbst and Rhyzopertha dominica Fabricius. Current Agriculture Research Journal, 12(2), 101–110.

Tiwari, S., Mentel, G., Mohammed, K. S., Rehman, M. Z., & Lewandowska, A. (2024). Unveiling the role of natural resources, energy transition and environmental policy stringency for sustainable environmental development: Evidence from BRIC+ 1. Resources Policy, 96, 105204.

Harborne, J. B. (1998). Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis (3rd ed.). Chapman & Hall.

Campbell, J. F., & Runnion, C. (2003). Patch exploitation by female red flour beetles, Tribolium castaneum. Journal of Insect Science, 3(1), 20.

Tapondjou, L. A., Adler, C. L. A. C., Bouda, H., & Fontem, D. A. (2002). Efficacy of powder and essential oil from Chenopodium ambrosioides leaves as post-harvest grain protectants against six-stored product beetles. Journal of Stored Products Research, 38(4), 395-402.

Nerio, L. S., Olivero-Verbel, J., & Stashenko, E. (2010). Repellent activity of essential oils: a review. Bioresource Technology, 101(1), 372-378.

Sattar, S., Arif, M., Sattar, H., & Qazi, J. I. (2011). Toxicity of some new insecticides against Trichogramma chilonis (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) under laboratory and extended laboratory conditions. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 43(6), 1117–1121.

Abbott, W. S. (1925). A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology, 18(2), 265–267.

Stopar, K., Trdan, S., Bartol, T., Arthur, F. H., & Athanassiou, C. G. (2022). Research on stored products: a bibliometric analysis of the leading journal of the field for the years 1965–2020. Journal of Stored Products Research, 98, 101980.

Trott, O., & Olson, A. J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 31(2), 455-461.

Mehta, S., Machado, F., Kwizera, A., Papazian, L., Moss, M., Azoulay, É., & Herridge, M. (2021). COVID-19: a heavy toll on health-care workers. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 9(3), 226-228.

Benelli, G., Pavela, R., Drenaggi, E., Desneux, N., & Maggi, F. (2020). Phytol,(E)-nerolidol and spathulenol from Stevia rebaudiana leaf essential oil as effective and eco-friendly botanical insecticides against Metopolophium dirhodum. Industrial Crops and Products, 155, 112844.

Rahman, M. M., & Watanobe, Y. (2023). ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Applied Sciences, 13(9), 5783.

Pandey, S., Krause, E., DeRose, J., MacCrann, N., Jain, B., Crocce, M., … & (DES Collaboration). (2022). Dark Energy Survey year 3 results: Constraints on cosmological parameters and galaxy-bias models from galaxy clustering and galaxy-galaxy lensing using the redMaGiC sample. Physical Review D, 106(4), 043520.